A look back at the highlights of a year like no other at the IGI.

There’s no need to beat around the bush: 2020 was a rollercoaster. We could take up several entire end-of-year roundups just on COVID-19 and the IGI team’s tireless work in our diagnostic testing lab and on rapid research projects. It’s impossible to understate what a proud moment it was when IGI founder Jennifer Doudna was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. With some improvisation, we found ways to celebrate the moment in a year when we are all kept apart. Amidst all of that, and even with labs operating at reduced levels because of the pandemic, the IGI kept running and researchers kept pushing genome editing to new and surprising places.

For this 2020 year-in-review, we wanted to share some of our most exciting news stories that you might’ve missed (COVID-19 not included).

1. Discovering huge phages – everywhere!

Early in 2020, IGI Director of Microbiology, Jill Banfield, published a major finding in Nature: huge phages containing novel CRISPR systems are prevalent across different environments and hosts.

“Large phages have been found before, but they were spot findings,” said co-author Rohan Sachdeva. “What we found in this paper is they are essentially ubiquitous. We find them everywhere.”

2. Those huge phages? They contain tiny surprises.

Some phages contain mini-Cas proteins that are opening new avenues for genome editing. One of the smallest Cas proteins known to date, the newly discovered CasΦ (Cas-phi) has advantages over current genome-editing tools thanks to its petite size, making it easier to deliver into cells to edit genes. CasΦ works in bacteria, animal, and plant cells, making it a promising genome editor with broad applications.

3. Engineering cassava to reduce cyanide

“Roughly a billion people around the world rely on cassava as a source of calories, including around 40 percent of Africans,” said Jessica Lyons, IGI investigator. The problem? Cassava contains a precursor of cyanide, which can lead to catastrophic health problems. An IGI project is using gene editing to remove the cyanide from this staple crop.

4. A year of pioneering women in science

While much of the IGI news of 2020 circled around the historic Nobel Prize in Chemistry win by Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, 2020 was a year filled with recognitions of the work of many other women scientists at the IGI. Pamela Ronald became the first woman to be named a World Agriculture Prize laureate by the Global Confederation of Higher Education Associations for Agricultural and Life Sciences. IGI Director of Microbiology Jill Banfield was honored with the 2020 Harold Urey Award from the European Association of Geochemistry recognizing her many contributions to the advancement of geochemistry, as well as the 2020 Advance Life Sciences Award from the Australian Governement. Melanie Ott and Jennifer Doudna both received the Inspire Award from the San Francisco Business Journal, recognizing the most influential women of 2020. Markita Landry received the 2020 Emerging Leader in Molecular Spectroscopy Award. Cara Brook, a postdoc in the Glaunsinger lab and an IGI COVID-19 Rapid Response Research awardee, was named a 2020 L’Oreal For Women in Science fellow. Jenny Hamilton, a postdoc in the Doudna lab and the technical co-lead for the IGI’s COVID-19 diagnostic testing lab, was named a 2020 STAT Wunderkind given to the most promising early-career researchers.

5. Getting a close look at a base editor

This year, we got the first look at a 3D structure of a base editor, which can bind to DNA and replace a single nucleotide with another.

“We were able to observe for the first time a base editor in action,” said Doudna lab postdoc Gavin Knott. “Now we can understand not only when it works and when it doesn’t, but also design the next generation of base editors to make them even better and more clinically appropriate.”

6. Plants have pandemics too — and we can help

New IGI research resolved the structure of a plant resistosome, showing how plants can directly recognize pathogens, and providing new options for scientists to help crop plants fight pandemics. The structure itself held an interesting surprise.

“As soon as I saw the structure, I thought, ‘Wow, that looks exactly like the folds I’ve seen in antibodies,'” said first author Raoul Martin.

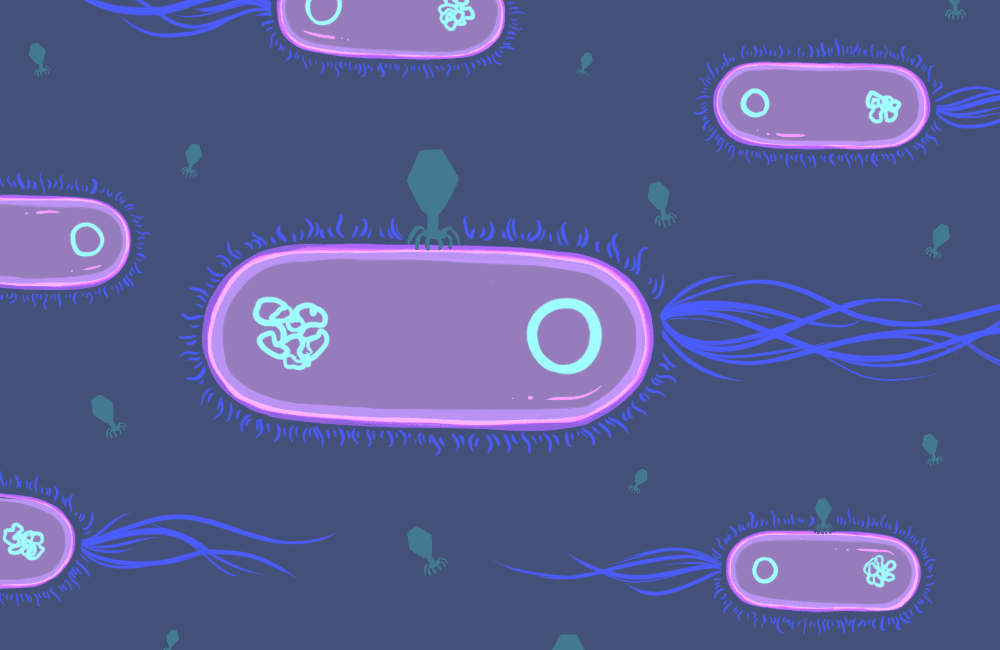

7. Fighting antibiotic resistance — with viruses

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most significant medical challenges of the day, but we’re not the first to tussle with bacteria. IGI researchers Vivek Mutalik and Adam Arkin looked for a different angle to fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria in research published this year: bacteriophages, the poorly understood viruses that infect bacteria.

“Whenever I isolate a phage it is with the hope that it is going to save somebody’s life. Maybe not now, but someday. That’s a very satisfying feeling,” said Mutalik.

8. Engineering E. coli to capture CO2 from the atmosphere

E. coli, bacteria that live in our guts and are commonly used in scientific research and biotechnology, usually get their carbon by eating sugars. A new study from IGI researchers showed that re-engineered E. coli can look for food in other places — including carbon dioxide from the air.

“Think about all the things you might possibly make out of microbes, like chemicals, biofuels, additives for food or even bulk edible protein, like imitation meats. For all of those things, why shouldn’t the carbon source be CO2? Why shouldn’t we pull it out of the air?” said first author Avi Flamholz.

9. Learning from chilly squirrels

Hibernators can survive extreme stress. In the winter, the body temperature the so-called “extreme hibernator” the Arctic ground squirrels drops below freezing, reducing blood flow to the brain by more than 90 percent. IGI researcher and 2018 SKCF Faculty Scholar Dengke Ma has revealed how they do it — and how it could help us create better treatments for stroke and heart attack.

“We humans may pride ourselves on our smarts, but the brains of Arctic ground squirrels have some key advantages,” said Ma.

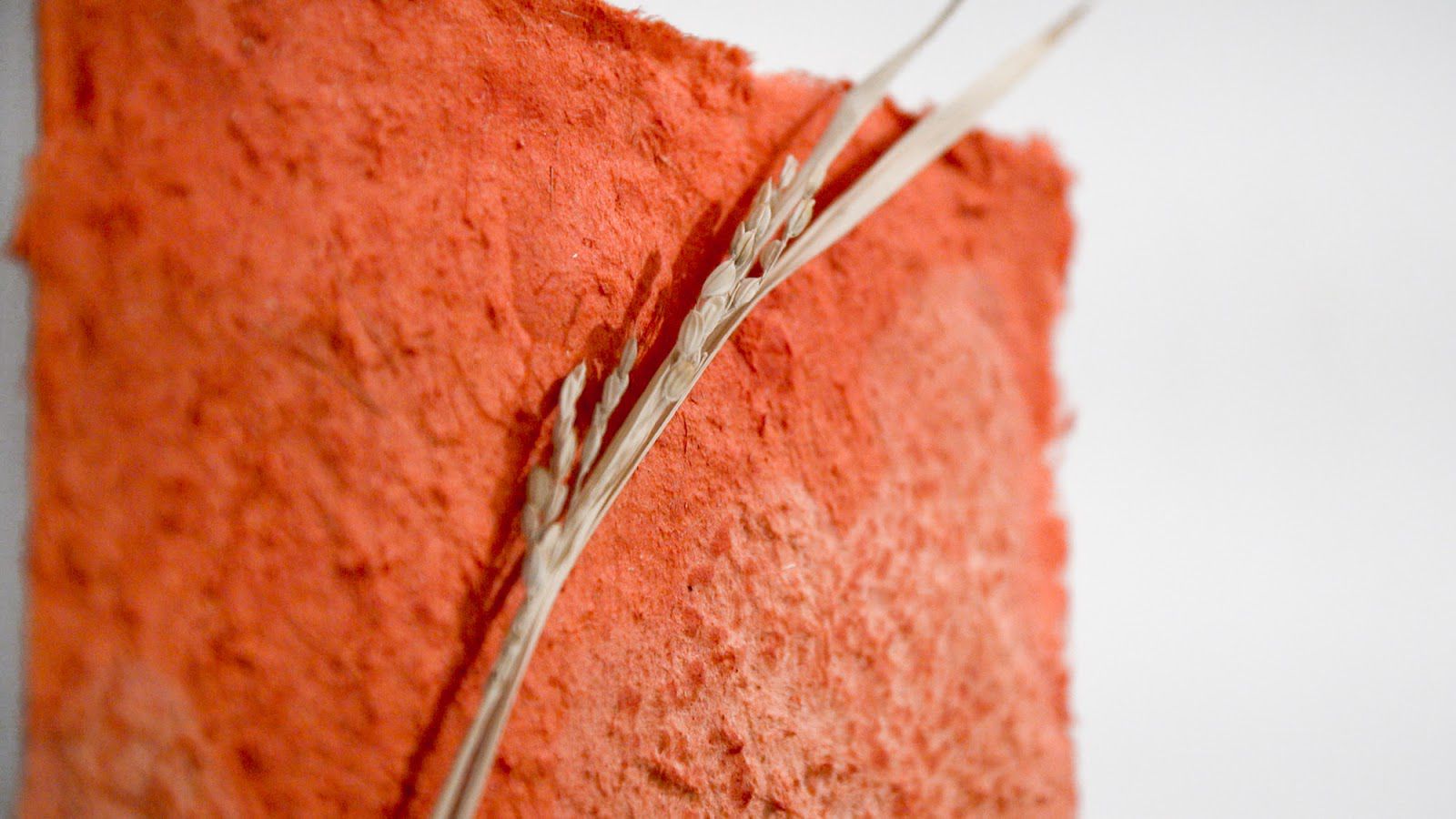

10. CRISPR isn’t just a scientific tool, it’s beautiful too

What happens when you introduce artists to CRISPR genome editing and then give them free rein to create art inspired by what they learned? We found out, and the results were as beautiful as they were unexpected.

Thank you for following along with the IGI and all of our work this year — we are looking forward to an even brighter 2021!