Speaker Spotlight: Roberto Zoncu

Undergraduate science communication intern Mira Cheng sits down with speakers from the weekly IGI Seminar Series to discuss their innovations, motivations, and eclectic hobbies.

Dr. Roberto Zoncu is an Assistant Professor in the Department Molecular and Cell Biology at UC Berkeley and the IGI’s first SKCF Faculty Scholar. I interviewed Dr. Zoncu when he spoke at the IGI on April 23rd, 2019. An abridged version of our conversation appears below.

MC: Could you please tell me a little bit about your journey in becoming a scientist?

RZ: “I grew up in Italy; I was born on the island of Sardinia, a beautiful place. My parents were both medical doctors and in elementary school I decided to be a scientist and try to cure diseases. I was only six years old and I said, ‘Someday, I’m going to go to America and cure diseases.’ And I stuck to the plan. I finished high school and college in Italy. I went to university in Pisa. Then when I graduated I decided to move on with my dreams, so I started to send letters to graduate programs in the US. It’s actually very hard to get into a program. I was lucky that a PI at Yale probably took pity on me and invited me to do a three-month internship. It was a culture shock, but I really liked it so I decided to stay. I did my PhD [at Yale] in Cell Biology. I was studying membrane traffic, how cells import and export nutrients, and when I graduated I wanted to continue and understand more about nutrient sensing. There was this leading lab at MIT, David Sabatini’s lab, who was doing work in this field so I applied and I joined his lab. I really liked it, and then [after my post-doc] I was ready for a change of scenery. I liked the idea of coming to a sunnier place where people have a work-life balance. I started my lab here [at UC Berkeley] four years ago and it’s been going well.”

RZ: “I grew up in Italy; I was born on the island of Sardinia, a beautiful place. My parents were both medical doctors and in elementary school I decided to be a scientist and try to cure diseases. I was only six years old and I said, ‘Someday, I’m going to go to America and cure diseases.’ And I stuck to the plan. I finished high school and college in Italy. I went to university in Pisa. Then when I graduated I decided to move on with my dreams, so I started to send letters to graduate programs in the US. It’s actually very hard to get into a program. I was lucky that a PI at Yale probably took pity on me and invited me to do a three-month internship. It was a culture shock, but I really liked it so I decided to stay. I did my PhD [at Yale] in Cell Biology. I was studying membrane traffic, how cells import and export nutrients, and when I graduated I wanted to continue and understand more about nutrient sensing. There was this leading lab at MIT, David Sabatini’s lab, who was doing work in this field so I applied and I joined his lab. I really liked it, and then [after my post-doc] I was ready for a change of scenery. I liked the idea of coming to a sunnier place where people have a work-life balance. I started my lab here [at UC Berkeley] four years ago and it’s been going well.”

MC: Who were your main role models throughout your journey?

RZ: “It’s kind of lame, but probably great Italian scientists like Galileo Galilei, Enrico Fermi—you know those guys were a source of inspiration. My elementary school teacher really communicated a love for science and open-mindedness. I think that is very important because if you are encouraged to ask questions when you are very young, then that’s what you want do for the rest of your life, but if [asking questions is] not something that you’re nurtured to do, it may be hard later.”

MC: What are some challenges that you’ve faced throughout your career?

RZ: “In general I would say I was lucky. I got into Yale and MIT, those are two places that give you training opportunities that you don’t find in any other place. Maybe when I was at Yale, as a green and inexperienced grad student, the hard thing was to really focus. There were so many things I was interested in, for a while I had a hard time deciding what I really wanted to do specifically.”

MC: How did you come to work on the project that you are going to talk about in the seminar lecture?

RZ: “I think the major reason is my background. Because I’m Italian, I love food and I especially love good food—I’m very picky about it. I’m always thinking about how to judge food. So for me it’s natural to think about how a cell picks and chooses what to eat and how to use it. Also, it’s a problem that has been underappreciated for a while. Now we are learning that it’s actually so important for understanding human physiology and diseases. The discoveries and surprises that come from studying this field are endless; you can make connections between different organs, different systems. There is a lot to learn. It also gave [my lab] an entry point into drug development.”

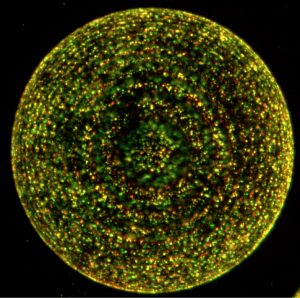

MC: How do you use CRISPR in your research?

RZ: “To me [gene editing] is an amazing tool for discovering new biology, especially if you can do it in an unbiased way. Traditionally, science has been hypothesis-driven. I think that with CRISPR we have this amazing ability to interrogate the whole genome at once, and find the places that are important to the process [we’re studying]. The pathway that we study is very complicated, there are many many parts, so by using CRISPR we can get a good lay of the land. It is also [important] in a therapy context. We’re doing drug development, and when you come up with a new compound you need to ask yourself, how does it really work? Can the cell come up with a mechanism of resistance? This happens in cancer all the time. People spend years and years developing an amazing targeted therapy, they give it to the patient, the tumor regresses, and then a few months later it comes back. We can use the power of gene editing to anticipate how the tumor will react to the drug, and we can block that adaptive response. That’s a whole universe to explore because for every new compound, you could predict how the cell will respond.”

MC: What do you hope to achieve with this project?

RZ: “The goal is to develop new compounds to manipulate nutrient sensing in disease contexts and to understand the biology around it and also anticipate the adaptive responses of the cell. We have a lot more to the project, we’re not done yet, but we’ve made good progress. And then as a whole in terms of directions for the lab, eventually we want to branch out into animal models: neurodegeneration, aging. [Contexts] where we can put to test these molecular discoveries that we are making. It’s challenging for a young lab to do everything.”

MC: What is something that you emphasize in your lab?

RZ: “I think in science it’s important nowadays to be collaborative, and to bring in people with different expertise. To me the most fun is when different labs with different expertise come together and do things that wouldn’t be possible in a single lab. This is something that people in other fields, like in physics, understand very well because they work in huge teams. In biology we tend to be more fragmented, each lab is its own universe, but that’s also something that is changing. In being able to share the glory, we can do better science.”

MC: Where do you see your field in ten years?

RZ: “I see a different knowledge of how metabolism is regulated, to the point where we can do more knowledgeable interventions. Maybe that’s a hope more than vision, but I think we are learning so much and we are on the cusp of being able to manipulate metabolism for diseases such as obesity and diabetes. The reason why there are so many debates about how to diet is because we don’t really understand the system. My hope is that in ten years we can really do targeted interventions where we can take a chronically obese person and give them meaningful strategies and drugs that can [help] them back to normal function. The possibilities are endless, it’s very exciting.”

MC: What is something that you do a lot that people wouldn’t necessarily expect?

RZ: “I cut my own hair. I haven’t been to a hairdresser in 15 years. I cut my hair probably once a week. It takes away my stress.”

MC: If you could describe yourself in three words, what would they be?

RZ: “Enthusiastic, positive, hopeful.”

MC: If you could listen to a conversation between any two people, who would they be?

RZ: “Christopher Columbus and the first Native American he met. They met each other from such different worlds.”

MC: What advice would you give young scientists?

RZ: “Keep doing what you’re doing. Looking back, there are always things you can do better. Set time aside to think carefully, don’t rush into things. Be enthusiastic, hopeful, and positive. Things will work out. There’s a lot of negativity today about opportunities in academia, doing science. Part of [the worries] are true and we cannot deny that, but the number of career possibilities for scientists are increasing constantly. To me having a Ph.D. well-done is a guarantee that things will work out. Be positive.”

By

Mira Cheng

By

Mira Cheng