CRISPR in Agriculture: 2024 in Review

Just 12 years after its development, the genome-editing tool CRISPR is being used in a wide breadth of ways in plant and animal agriculture, from reducing waste to adapting plants and animals to climate change, from making plants that naturally resist weeds to ones that can be harvested more efficiently, from food to biofuels and paper. Each year, researchers are adapting CRISPR tools to be used in new species, for new purposes. In this article, we’ll go over the basics of genomic engineering in agriculture and then map out some of the most exciting new developments, like never-before-seen seedless berries, non-browning avocados, and THC-less hemp, as well as updates on research areas we covered in our 2022 review — plus what to watch for next!

CRISPR MEETS AGRICULTURE

Genetic modification has been used in varying forms for centuries to create crop plants with desired traits like making watermelons that are sweeter and with have fewer seeds, and domestic farm animals with traits like high milk production in cows. In the past decade, CRISPR has set itself apart as the go-to gene-editing technology largely due to its unparalleled speed, accuracy, and versatility.

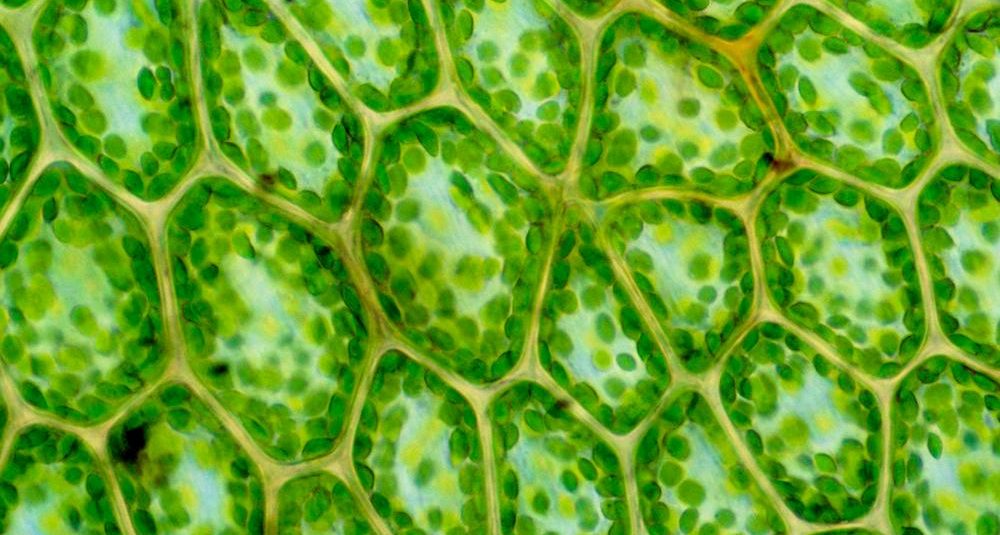

The traditional CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing system can be likened to a pair of molecular scissors which scientists can program to cut the DNA double helix at specific locations in the genome. Edits to plants and animals via CRISPR are typically introduced to “knockout,” or eliminate the function, of a particular gene to get a desired trait, but as you will see in this article, CRISPR can be used in a variety of ways. Learn more about the mechanics of CRISPR and uses in agriculture in our CRISPRpedia chapters on CRISPR technology and CRISPR in agriculture.

The lengthy process of developing a genetically modified agricultural product, whether a plant, animal, or otherwise, starts in the lab with intensive research, optimization, and validation — a timeline that can take several years from start to finish. The process often includes examining performance in field-like conditions in a process known as field trials. These experiments can provide key evidence to regulators that a particular genetic modification will have the intended effect and pose minimal risks to the natural environment or human health. The product is then generally submitted to regulatory agencies (e.g., the USDA) for review. Upon approval and deregulation, the developer may then begin the marketing, scaling, and distributing to growers or consumers. Similar processes are in place all over the world with slight variations about what criteria must be met prior to an approval. Note that some countries require producers to prove that their product has the intended edit and does not contain any genes that come from a different organism.

We’ll break down exciting new developments using CRISPR in agriculture and for each example we’ll note how far along in development the product has come, from initial research stages to completed field trials.

GRAPHIC SUMMARY

EDITING FOR THE EATER

CRISPR is being used to edit crop plants to deliver on wide-ranging food interests for consumers. Whether it’s optimizing taste or texture, enhancing the nutritional profile, or extending the shelf life of some of our favorite foods, the future of food is closer than we might imagine. This section spotlights projects harnessing CRISPR to engineer better potatoes for chipping, seedless blackberries, and non-browning bananas and avocados! We’ll provide brief updates on a few products introduced in our 2022 article.

Putting the CRISP in CRISPR

Potatoes put in cold-storage have the tendency to accumulate chemical precursors which, upon high-temperature treatment — like frying — can be converted to the potentially carcinogenic compound acrylamide. To give you a friendlier French fry, researchers at Murdoch University in Western Australia introduced a CRISPR-Cas9 system to one of the most popular potato “chipping” cultivars, Atlantic, and used it to then disrupt the genes responsible for the synthesis of these precursors. Their edited potatoes showed a dramatic reduction in the chemical precursors after cold-storage. The team even went a step further and found that chips (“crisps” for our friends down under) made from these edited potato varieties had up to 80% less acrylamide. One bag of sea salt and vinegar, please!

Needless to say, seedless blackberries are on their way

Pairwise, the company that developed the first CRISPR-edited food available in North America (more to come on those leafy greens!), made a splash in Summer 2024 when they announced the advancements they’ve made in engineering the world’s first seedless blackberries. To achieve this, scientists at Pairwise used proprietary CRISPR technology to target genes responsible for the tough seed pits found in blackberries. The resulting blackberries, though not truly seedless, contain softer, chewy seeds similar to what we find in our favorite “seedless” grapes and watermelon. To further improve this variety, other edits were made to eliminate thorns and allow the plant to grow more compactly. The “stacking” of these traits is common for plant breeders, in an effort to make varieties that are better for both consumers and growers. These seedless, thornless, compact blackberries have entered field trials and are working towards upscaled commercialization. The toothpick industry should be scared.

Non-browning avocados

“Refrigerate! Keep the pit! Lime juice!” The age-old question of how to keep your avocados green and fresh rages on. Scientists at GreenVenus are looking to put this debate to rest by engineering a non-browning avocado using CRISPR technology. Following in the footsteps of what was previously accomplished in apple, banana, and mushrooms, this non-browning avocado was achieved by disrupting an enzyme, polyphenol oxidase, crucial to the browning process. Although yet to be scaled, GreenVenus reported success in multiple commercial varieties and hopes this breakthrough will help reduce food waste by improving the avocado’s shelf life. Soon we’ll have no choice but to eat that week-old avocado in our kitchens… Guac, anyone?

Updates: The first CRISPR-edited product hits US markets & more

Bitterless mustard greens, the first CRISPR-edited product in American grocery stores

In our 2022 review, we introduced you to what would become the first CRISPR-edited product on the North American market: bitterless mustard greens! The distribution of these leafy greens was initially limited to a handful of food service locations nationwide. The company behind the development, Pairwise, recently struck a deal with Bayer to expand commercialization of the ground-breaking green and bring it to a grocery store near you.

Non-browning banana given a green light in Philippines

While we patiently await ongoing commercialization efforts to bring non-browning bananas to our local produce section, Tropic Biosciences — the company behind the CRISPR-edited fruit — has been busy spreading the word. During the summer of 2024, the Philippines Department of Agriculture and Bureau of Plant Industry deemed the edited bananas non-GMO and gave the green light for import and propagation.

Vitamin D tomato

Initial work engineered edits to overproduce precursors for vitamin D which would accumulate after exposure to UV light in lab tomatoes. Expect similar modifications to be applied to commercial tomato varieties next, as well as other vegetable relatives from the nightshade family like eggplants, potato, and peppers.

EDITING FOR FARMERS

Current levels of crop production are unlikely to meet the projected doubling of global food demand by 2050. Among the multitude of challenges farmers face, pest management in crops and the spread of infectious diseases among livestock are two challenges that can result in suboptimal yield for growers. This section presents exciting new projects using CRISPR to boost resilience to pests and disease, as well as optimizing crop architecture to make harvesting easier. We’ll also bring you brief updates on products mentioned in our past article.

Witch, please…

Sorghum is a fundamental cereal crop grown globally, providing a major source of grain for food and feedstock. In Africa, however, sorghum yield is threatened by the omnipresent, parasitic plant Striga hermonthica, also know as “witchweed,” seeds of which can be found in over half of available farmland. Chemical compounds from the roots of sorghum trigger the growth of witchweed seeds which then promptly invade the sorghum root system to sneakily swindle water and nutrients at the expense of the sorghum host. Naturally resistant wild sorghum varieties do exist and are able to withstand infestation due to gene variants which change the compounds that normally help witchweed seeds grow. Researchers at Kenyatta University in Nairobi, Kenya are aiming to recapitulate these helpful mutations in domesticated sorghum varieties using CRISPR with hopes it will provide some resistance to infestation without relying on the presence of transgenes or foreign DNA. Edited sorghum seeds underwent field trials this summer, making them one of the first to hit African soil. Double, double, withweed’s in trouble!

Catfish with a side of alligator, *chef’s kiss*

In aquaculture, loss due to infectious diseases can put a huge financial burden on fish farmers. Antibiotics are routinely applied to treat outbreaks but over-reliance increases the risk of developing resistant bacterial strains and can have adverse effects on human health. A promising alternative approach is to use antimicrobial peptide genes or AMGs, which integrate into the host’s genome and provide improved resistance to a suite of pathogens. Historically, transgenic introduction of AMGs has relied on inserting the AMGs at a random spot in the genome which can lead to problems if it is lands in an existing gene or locus of importance. In a recent proof-of-concept approach, a research group out of Auburn University harnessed a CRISPR-Cas9 system to insert an alligator-derived AMG known as cathelicidin into the genome of blue catfish in a specific location in the genome. To achieve this specificity and prevent the potential for unwanted spread of the transgene, the cathelicidin gene was inserted in a spot that would stop female catfish from reaching reproductive maturity unless treated with external hormones. In other words, the catfish with AMG will only be able to reproduce and pass on their genetic material in a highly controlled manner (i.e., aquaculture breeding). The research team showed improved survival and bacterial resistance among transgenic blue catfish and had no impact on overall growth or morphology. Transgenic approaches such as this inherently come with more regulatory hurdles, but this new line of disease-resistance blue catfish can help aquaculturists mitigate the use of traditional antibiotics and sets a precedent for engineering transgenic livestock via modern gene-editing techniques. Who’s coming to the fish fry??

Early-flowering cowpeas make mechanized harvest possible

Cowpeas, or black-eyed peas, are a tropical crop which provide a vital source of protein and carbohydrates for both humans and livestock. While many crops stop growing once they reach sexual maturity, a defining feature of some field-grown cowpea varieties is their ability to grow continuously. This causes them to flower and develop seeds in an asynchronous manner which makes harvesting in bulk difficult to manage. In early 2023, scientists at BetterSeeds announced their intentions to begin field trials of the first gene-edited cowpea that allows for mechanized harvest. To achieve this, proprietary technology was used to introduce CRISPR editing tools that targeted genes responsible for plant architecture and flowering time. The resulting edited cowpea plants grew stronger vertically and flowered in sync, making mechanized harvest possible. These bushy cowpeas were deregulated by the USDA late last year. MOOoove over soybean, there’s a new bean in town.

Update: Anti-lodging teff passes USDA regulatory review

In our 2022 review, we described the gene-editing approaches being taken in teff, a vital grain crop in Ethiopia, to reduce losses due to “lodging,” the process in which stems buckle under the weight of heavy grains near the top of the plant. The USDA has since deemed that the edits introduced to develop this anti-lodging teff are unlikely to pose any increased risks and have deregulated their use. Next up are field trials!

EDITING FOR A DYNAMIC PLANET

In 2023, global temperatures reached their highest in recorded history and 2024 is on pace to take over as the single hottest year on record. This unprecedented increase in temperature is closely linked to human-caused emission of greenhouse gasses. Increased temperatures usher in unpredictably severe weather patterns, droughts, and saltier soils — all of which put global agricultural productivity at risk. We previously highlighted gene-editing efforts to mitigate these effects which included boosting heat tolerance in cattle and improving disease resistance in wheat and pigs. This section will feature ongoing projects to develop crops for alternative fuel sources and better suited to a changing climate.

Gene-edited pennycress has got you covered

Reducing our reliance on fossil fuels and shifting towards renewable energy sources will be crucial in efforts to fight climate change. Oilseed crops — as the name suggests — are plants grown for their oil-rich seeds which can be used in culinary and industrial applications. Oil derived from soybean, sunflower, and canola are among the most common in the United States. Soon we might be adding CoverCress to the list, a gene-edited variety of pennycress developed by the ag-tech company of the same name. Pennycress is a common weed from the cabbage family that grew in popularity over the past few decades as a cover crop for the off-season winter months. Its high oil content (>30%) makes it especially suitable for biofuels and feedstock, but it hasn’t found commercial foothold yet partially due to high levels of erucic acid (a potentially toxic compound in large doses) and susceptibility to seed shattering, or unintended dispersal of seed. To develop an improved field variety of pennycress, researchers at CoverCress knocked out genes necessary for the accumulation of erucic acid and seed shattering. The edits in pennycress were reported to reduce erucic acid content in seed oil to below 2% compared to the >35% found in unedited pennycress. Similarly, the edits were reported to reduce premature seed shattering by up to 90%. These agronomic improvements, along with others being developed at CoverCress, were made possible by combining precise gene-editing tools with traditional crop breeding techniques. CoverCress has been deregulated by the USDA and the first efforts for commercialization began in 2023.

More sustainable trees? It’s a poplar choice

Whether it’s the paper bags you use to carry your groceries, the cash used to purchase said groceries, or the receipt reminding you that buying organic saffron in bulk does not make it any cheaper, paper and other wood-based products are a mainstay in our everyday lives. Despite their ubiquity, application of gene-editing tools in trees has lagged compared to other crops, in part owing to their long lifespans and complex genomes. In a recent breakthrough effort, researchers at North Carolina State University successfully deployed CRISPR in poplar trees to enhance wood properties for fiber production. A major bottleneck in wood fiber processing is the lignin present in the trees. Lignin gives trees their rigid structure, allowing them to reach impressive heights. For wood fiber mills, however, high lignin limits their processing efficiency. As you might imagine, simply removing lignin synthesis from trees altogether comes at the cost of tree growth. Instead, the research group at NC State applied a complex gene-editing strategy using CRISPR which concurrently targeted up to six different genes involved in the biosynthesis of lignin and other woody carbohydrates. The edits led to a simultaneous increase in carbohydrates vital for wood fiber and modest reduction in lignin content, all without hampering the overall growth of the tree. Wood from these CRISPR-edited poplar trees would potentially be more suitable for fiber production and reduce the environmental impact associated with industrial wood processing. The research team next hopes to conduct long-term field trials with the edited poplar varieties.

Rice CRISPR treat

With the global population expected to reach nearly ten billion by 2050, the need for crops with improved productivity and climate resilience has never been stronger. Optimizing photosynthesis, the fundamental process by which plants use light energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into biomass like leaves and grains, is one promising approach. Previous research has shown that transgenic overexpression of certain photosynthesis-related genes can lead to improved efficiency and higher yields. The presence of transgenes, however, leads to more stringent regulation and can be susceptible to silencing across generations. To avoid these potential complications, a research team led by IGI Investigator Krishna Niyogi used CRISPR to generate transgene-free overexpression of a key photosynthetic gene in rice. Niyogi’s team achieved this by targeting the DNA sequence adjacent to a gene, which controls when and how much protein is made from the gene, with multiple simultaneous editors. This led to a “reshuffling” of the DNA sequence which resulted in the increased protein production by the unedited gene. These edited rice plants had improved ability to withstand damage caused by high light intensity and enhanced water use efficiency. Efforts like these highlight CRISPR not only as a gene-editing tool, but as a genome-editing tool capable of editing virtually any part of the genome, not just the sequences that encode proteins. As we deepen our understanding of crop genomes, expect these tools to be used in increasingly creative ways.

Updates: Cattle with a haircut & virus-resistant pigs

Welfare review finds slick-coat cattle better off under current condition

In our 2022 review, we highlighted the FDA-approved, gene-edited beef cattle notable for its heat-resistant slick coat. A recent review analyzed the welfare benefits of these “heat tolerant” cows and found there to be minimal unintended effects compared to their unedited counterparts, none of which form a risk to the safety of the animal. However, the authors argue that while edited cattle are more temperature tolerant under current agricultural conditions, net welfare improvement could be negated in environments with extreme stressors. Heat-tolerant does not mean heat-immune. But a cow with a parasol and sunglasses would be pretty cute, just saying… Read more about this case study in our CRISPRpedia chapter on CRISPR & Ethics.

New approach leads to virus-resistant pigs

The UK-based company Genus used a CRISPR-Cas9 editing approach to disrupt a cell surface protein implicated in viral infection to protect piglets from porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, a deadly disease that affects pigs worldwide. A similar approach on a different gene discussed in our previous review was effective but resulted in unexpected side effects including cataracts. Genus introduced this new approach into multiple commercially viable pig varieties and are hoping to see them deregulated by the in the coming months.

WHAT’S YOUR VICE?

Kary Mullis, the Nobel Prize-winning inventor of PCR, has said on record that the seminal technique is unlikely to exist had it not been for his habitual use of psychedelics. While we obviously cannot and do not condone ingestion of illicit substances, indulging in guilty pleasures like a sweet treat or glass of wine is a common ground at which consumers, farmers, and researchers alike can meet. This section highlights ongoing gene-editing efforts to reimagine some of your favorite consumables. Enjoy responsibly!

Reefer reformulated

With recreational cannabis now legal in over half of the United States and nearly a dozen more states acknowledging its medicinal benefits, there’s no denying the marijuana boom. Researchers at the University of Wisconsin Crop Innovation Center are leading the charge in engineering gene-edited cannabis varieties after they developed Badger G, a non-psychoactive strain designed to reduce crop loss. Those who ingest recreational cannabis products tend to experience the psychoactive and analgesic effects brought on by high levels of cannabinoid molecules found in flowers, typically in the form of THC or CBD. Other parts of the hemp plant have been used to make hemp fibers, which has been used to make cloth for tens of thousands of years, as well as products like paper. However, under current restrictions enacted by the 2018 Farm Bill, hemp material exceeding a 0.3% level of THC cannot be used for industrial purposes. This can lead to roughly a quarter of the crop being discarded. In an effort to reduce waste and develop a more industry-friendly variety, the research group at the University of Wisconsin used CRISPR to knockout of the CBDAS gene which is necessary for the biosynthesis of CBD and THC. Edited cannabis plants subsequently fail to synthesize both CBD and THC. Badger G was deregulated by the USDA earlier this year, giving the go ahead for commercialization and crossbreeding. Hemp yeah!

Chardonnay, you stay! Improving disease resistance in grapevine

We’re inching closer to a time in which you might be sipping some of your favorite wines made from CRISPR-edited grapes. This is highlighted by collaborative efforts like VitisGen, a decades-long USDA-funded project to facilitate the development of improved grapevine varieties. One of the primary goals of the project is to understand the genetic basis that gives some grapes resistance to powdery mildew disease, a fungal pathogen plaguing some of the world’s favorite varieties. Leveraging tools like CRISPR, this information can then be harnessed to introduce the same resistance-enabling genetic modifications to Chardonnay grapes, for example, without altering favorable attributes pertaining to its color or taste. This approach can also reduce the amount of pesticides necessary to treat disease outbreaks. Other ongoing projects aiming to optimize Cas variants for grapevine and improve resistance to other fungal pathogens have seen successful outcomes. ¡Salud!

Sweet tooth? Optimizing sugarcane architecture

Those looking to satisfy a sweet tooth may soon be in luck. Researchers at the University of Florida recently published their work introducing a CRISPR system into sugarcane to improve yields. Sugarcane represents one of the most globally recognized crops and, as its name suggests, is one of the primary sources of common table sugar. Efforts to genetically modify sugarcane in a targeted manner have proven difficult, partially due to its large, complex genome and difficulties related to delivering genomic tools and regeneration. The UF research group recently overcame these obstacles and introduced edits to sugarcane genes thought to be responsible for leaf architecture and development. More specifically, the group of genes being targeted are involved in developing the ligule, or the part of the leaf that attaches to the primary stem. By modifying these genes the team was able to alter the angle at which the leaves emerge from the primary stem, thereby increasing the efficiency of light capture. In one particular strain, the researchers showed that a modest 12% knockdown of the target gene was sufficient to decrease leaf angle by roughly half, leading to an impressive 18% increase in biomass. Future field trials will elucidate whether the introduced mutations have an impact on overall sugar yields and whether other physiological changes can further enhance sugarcane. There’s a dentist joke in here somewhere…

EXPANDING THE CRISPR TOOLKIT

The traditional CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system is often likened to a pair of molecular scissors that scientists can program to cut DNA at a specific spot in the genome. When DNA is cut, it creates the opportunity to change the DNA at the cut site. The core components comprising the CRISPR-Cas9 system include the Cas9 protein (the “scissors”) and a guide RNA molecule, which directs it to the specific spot in the DNA. Learn more about the biology of CRISPR with IGI’s educational resources, which span from basic to advanced.

Changes to the Cas9 enzyme, the guide RNA itself, and the discovery of new DNA-cutting Cas proteins expand our gene-editing capabilities and provide new tools scientists can use in their favorite agricultural systems. This section highlights some of the recent innovations in CRISPR-Cas technology to improve its accuracy, efficiency, and use it in a broader range of species.

A new Cas9 for editing plant genomes

A research group based in China recently reported a new Cas9 protein found in the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus rhamnosus. This variant, named LrCas9, edits DNA more efficiently than traditional Cas9 in plant cells from a variety of crops including rice, wheat, tomato, and larch trees. The research team also modified the LrCas9 protein so it can do a version of CRISPR-based editing called base-editing, where small DNA changes are made without cutting the DNA double helix, as well as turning genes “on” and “off”. Scientists can find their materials on AddGene.

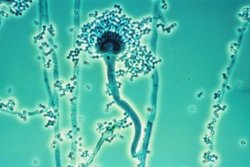

Fungus among us

Most genome-editing efforts in agriculture focus on plants and animals. But what about fungi? Researchers at UC Berkeley recently developed a biology toolkit, including a CRISPR-Cas9 system, for Aspergillus oryzae. This edible fungus is known for its role in the fermentation of products like soy sauce and miso, and has potential to be used in the alternative meat industry due to its high protein production and desirable texture. Using their newly developed toolkit, the team was able to improve the nutritional and sensory qualities (e.g., color and texture) of the fungus. The fungal strains and molecular toolkit are available for researchers through the JBEI Public Registry site.

Did you wanna make it a combo?

A research group based at the University of Maryland developed a modified CRISPR-Cas system that they called CRISPR-Combo that lets scientists edit genes and turn them “on” – meaning, get the cell making the protein encoded by the gene – at the same time. They used this system to introduce a visual clue to rapidly tell scientists which plants are edited simply by sight. Scientists can find their materials on AddGene..

WHAT TO WATCH FOR

The past two years have ushered in a slew of exciting CRISPR-edited agricultural products and prospects including nutrient-enhanced tomatoes, pathogen-resistant fish and cereal crops, and potatoes that might make for healthier chips and fries. While we’ve yet to see CRISPR-edited products hit the shelves en masse, and questions remain about consumer acceptance, notable advancements have been made in the deregulation of gene-edited crops and push towards commercialization. These advancements, driven by efforts in both the academic and private sector, allow researchers at companies like Pairwise and CoverCress to promise fruits and veggies of the future like the seedless blackberries and enhanced pennycress. Pairwise has even recently announced major breakthroughs on efforts to develop a pitless cherry variety!

Consumers, farmers, and climate researchers alike stand to benefit in the seemingly endless gene-editing possibilities which CRISPR provides, as well as the pace and creativity with which scientists are deploying it in their favorite systems. As CRISPR-based gene-editing tools become more sophisticated, expect to see equally complex editing strategies like targeting multiple genes at once, multi-function Cas enzymes, adding new genomic material at specific spots in the genome, and edits leading to programmable changes in how much protein is made from a given gene. We also anticipate CRISPR optimization to expand beyond staple crop species into more genomically complex plant and animal species, commercial crop varieties, and divergent cultivars grown on small-scale farms. A one-size-fits-all CRISPR-Cas system may not exist, but as the gene-editing toolkit expands, so will the breadth of products edited for the benefit of humans, growers, and the planet.

By

Tonio Chaparro

By

Tonio Chaparro