COVID-19 Research Spotlight: Laleh Coté on Virtual Mentoring

Laleh Coté is the STEM Education Specialist in Workforce Development & Education at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and a doctoral student in the Graduate Group in Science & Mathematics Education (SESAME) at the University of California, Berkeley. In April, she began working on an IGI-funded research project looking at how mentor-mentee relationships in the sciences have been impacted by the transition to virtual mentoring during the COVID-19 pandemic. In July, she talked with IGI science writer Hope Henderson about this project.

How did you get on the path to becoming a science education researcher?

I dropped out of college the first time around. When I went back to school to study biology, I basically had to get a 4.0 to get off academic probation. The thing that was most critical in my education was a summer research internship at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab.

After finishing my BA at San Francisco State University, I started working at Berkeley Lab coordinating research internships — the same programs that impacted me so much. I got really interested in thinking about how one might do research in science education to actually improve programs. In 2016, I started my PhD at UC Berkeley in science education. I’m finishing up the last year or so, while continuing my job at the Lab.

How has COVID-19 affected your research?

I was developing some projects to look at mentoring practices in science research experiences, and then after COVID hit I had to totally redesign them.

I knew that COVID was impacting education because I myself helped to transition programs from in-person to virtual experiences in those first few months. So, I thought, why don’t I study this phenomenon? What are mentors and mentees experiencing? Can we generate some information about best practices to support their success? So I created a research study that IGI has now funded.

How are you doing data collection?

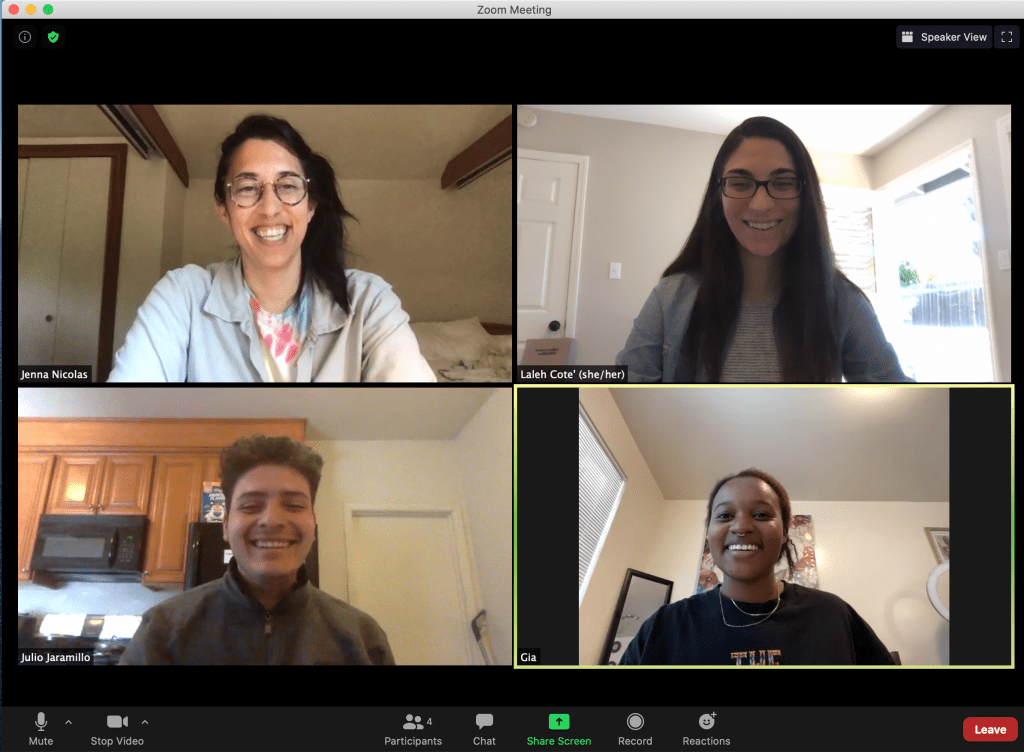

The primary way that we collect data from almost everyone in the study is to conduct an interview or two. We’re also capitalizing on the fact that everyone is now meeting remotely. We record Zoom meetings between mentors and mentees. A mentor might say, “I do X, Y, and Z all the time and it’s working really well.” And then when I observe them, I might see that they aren’t doing those things and it’s not going well! So, this adds a real dimension of truthfulness to the study.

What were your hypotheses or predictions when you started this project?

I deliberately tried to turn off my assumptions so that I could actually come into interviews with people with an extremely open mind. That’s a real game that you have to play with yourself because we naturally bring our assumptions with us.

Can you give us a peek into some of the observations you’ve had so far?

The current stressors in people’s lives are forcing mentors and mentees to share more personal information about themselves. Mentees and mentors are both talking more about their mental health and well-being, and their work-life balance. It’s an opportunity for increased and improved communication moving forward.

Another observation is that virtual communication is more formal, meaning that spontaneous “water cooler” conversations can’t happen as easily. Mentees are telling me, “I don’t want to bother my mentor” — at the same time, they are more isolated from their institutions and peers. So, this is a real conundrum.

With remote learning for children, we’ve seen that certain groups are really struggling. The inequalities in our society are magnified by the circumstances. Are you concerned that there are certain university student groups might be having a tougher time with remote learning and mentorship?

I am concerned about that. The most vulnerable, the most stressed out, the people that are struggling most with internet connectivity — they aren’t going to have time to participate in a research study. So, there are going to be voices that are still unheard, but that are extremely critical to our understanding of access to education. That is a limitation of this research.

What does the big shift towards remote school and work mean for disability access?

Beyond mentoring, the larger theme that keeps coming up for me is access. The issue of access comes up for people with disabilities, but also other reasons — people who live far away from a school, people that have a small child and so on. I’m a grad student who literally has never once applied for an internship because I have a six year old. It’s not just that I can’t leave him at home. I don’t want to! So, access can also be about preference. Not just what you technically can or cannot do.

For research experiences, the virtual environment creates compelling possibilities for who can collaborate with whom, and when, and how. Several mentees in the study have told me that they were happy they didn’t have to relocate for a research experience.

I have also worked with mentees in the past that have had visible or invisible disabilities. In some cases, the accommodations made for them were not sufficient. Even if they could get through their day, it didn’t feel empowering to be in that situation. I think more people will have more access as a result of all of this, too, not only to educational opportunities, but also to professional opportunities. That would be an awesome outcome!

Is there anything else you want to share?

Getting funding for a project that I feel so deeply invested in really gave me a boost! It fills me with excitement and energy. So, thanks to the IGI for that!

You may also be interested in

Meet an IGI Scientist: Bruce Conklin

IGI Awards $1 Million to COVID-19 Rapid Response Research Projects

Wolf Prize Laureate Brian Staskawicz on 40 Years of Plant Immunity Research

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson