This series introduces the public and fellow researchers to our talented scientists. We interview different IGI members to find out who they are and what makes them passionate about science.

—

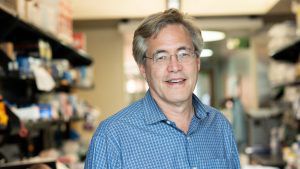

Bruce Conklin, M.D. is the Deputy Director of the IGI, a Senior Investigator at the Gladstone Institutes, and a Professor of the Departments of Medicine, Ophthalmology, and Pharmacology at the University of California, San Francisco. The Conklin lab is developing genome surgery methods to treat severe monoallelic genetic diseases of the retina, motor neurons, and cardiomyocytes.

Where are you from?

I was born in New York City, and I was raised in New Haven, Connecticut and near Banaue, Philippines.

Why did you become a scientist?

Many people to contributed to my decision to pursue basic research, but one that stands out was a patient we’ll call Angie, who has severe schizophrenia and active hallucinations. Angie’s hallucinations helped me see the importance of basic science in medicine.

I met Angie when I was a medical student on my psychiatry rotation in a public hospital in Cleveland. I vividly remember Angie describing body parts floating around the room that were as real to her as my own hands are to me. But I was most struck by the complete inability of the psychiatrists to provide an adequate explanation of what was wrong with Angie. It was a “the emperor has no clothes” moment where I realized that we know almost nothing about the basic science of disease. My prior studies were focused on health policy, but I realized I needed to gain experience in basic science. I had the opportunity to spend two years working with Julius Axelrod, who was a leader in neuropharmacology at NIMH. After that I knew I would spend my career in basic science research.

What do you like to do besides research?

Hiking, traveling. The common theme in my favorite trips is watching animals. I have had the good fortune to spend over 12 months in East Africa & South Africa during 5 different trips. I can easily spend an afternoon following a herd of elephants or a group of baboons!

If you discovered a new protein, what would you name it?

Twiga, which is the Swahili word for giraffe. One of my favorite animals!

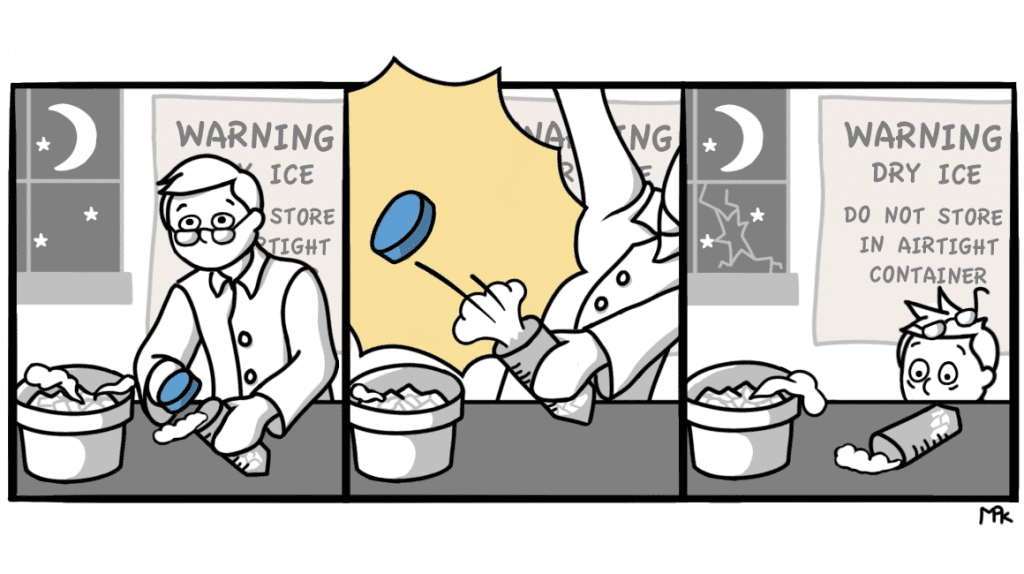

Describe a funny memory you have of working in the lab or in research.

One night, working late at night, I was processing a sample in a 50 mL conical tube, and I included dry ice to keep it cold. A few minutes after I capped the tube, it blew up with a sound like a bomb! Fortunately no one was hurt, so I can laugh about it now.

What would you do if you weren’t a scientist?

I would be a historian. I was considering this as a profession, but my Berkeley professor explained that it is nearly impossible to get a job (still true). I still enjoy studying the history of science. Everything we do is shaped by history.

How has science changed since you started as a researcher? What has been the most important advancement in your opinion?

- Science has become much more competitive with the increasing rise of the biotech industry and many more researchers.

- The speed and globalization of science increases every year.

- There are many more women in science, which is great! But we still have a long way to go on this front, particularly at the faculty level.

What role do you think science plays in the community and in the world?

Every year biotechnology plays an increasing role in all parts of everyday life. I am particularly interested in how the general public is learning more human genetics. I predict that will continue and lead to a new appreciation of the work we do at IGI.

Tell us about someone or something that inspires you.

Mahatma Gandhi, for his nonviolent resistance movement. His efforts not only won independence for India, but also inspired Martin Luther King, Jr., Nelson Mandela, and many others

Anything else you want to tell the world?

My parents had a major impact on my interest in science. My mother, Jean Conklin, was a research associate at Yale, studying optic nerve regeneration in newts. When I was growing up she never missed a chance to encourage my curiosity about nature. She hosted a 8th grade science club where we examined fertilized chicken eggs, made electric motors from scratch, and visited labs at Yale.

My father came to UC Berkeley in 1943 (from New York) as an undergraduate specifically because of the superb anthropology department and Alfred Kroeber who shared his passion for Native American studies. My father spent his career studying native cultures in the Philippines and I spent several years in a field station in the Philippines in a village surrounded by jungle. In this village, there were lots of pets including a rooster, cat, pig, cynomolgus macaque monkey and flying lizards. One year in the field is documented in a book my mother published called Ifugao Notebook.