Using Tricks from Viruses to Get Inside Cells

The past 12 years have seen the rapid development of CRISPR as a genome-editing tool and therapeutic reagent that can cure sickle cell disease and is being tested in tens of other clinical trials. Despite this progress, there are still challenges to realizing the full potential of CRISPR. The biggest challenge is delivery — getting CRISPR genome-editing components into the right cells and tissues (and making sure they don’t get where they’re not needed).

In a new paper published in PNAS, Jennifer Doudna and researchers in her lab collaborated with Randy Scheckman, another UC Berkeley professor and fellow Nobel Laureate, to advance a potential CRISPR delivery system called enveloped delivery vehicles (EDVs), which the Doudna lab has been developing for several years. IGI Investigator Eva Nogales was also a collaborator on the research.

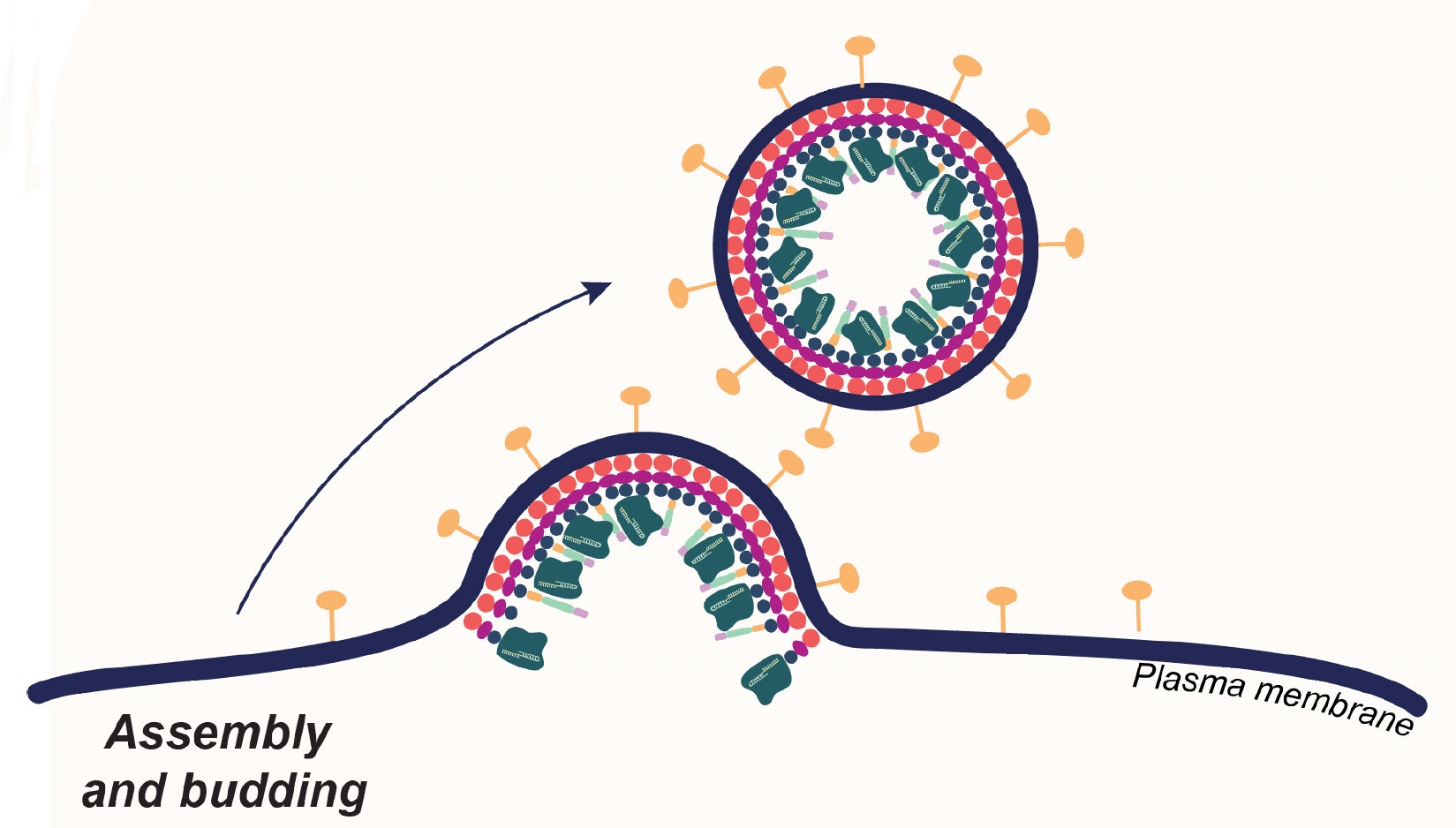

CRISPR and other genomic medicines are most commonly delivered to patients’ cells using viral vectors. Viruses rely on a number of tricks to gain entry into cells, where they then typically cause infection. Viral vectors are viruses that have been defanged so they don’t cause infection, but can still get into cells. Although they are a crucial tool, they carry some risks. The biggest risk is that the virus will trigger an immune reaction in patients. Even though patients are prescreened, severe reactions and even death occasionally occur.

The first generation of EDVs, developed by Doudna lab researchers Jenny Hamilton and Connor Tsuchida, took advantage of viruses’ natural ability to sneak into cells, using genetic engineering to get the particles to package the CRISPR enzyme Cas9 inside. EDVs can get into cells, delivering the CRISPR components. And they can be engineered to have specific proteins or antibodies on their surfaces, which directs them to specific cell types.

“Jenny and Connor did a lot of wonderful work showing just how powerful these systems are at transporting editors into the cell by relying on native viral machinery,” says co-first author Wayne Ngo. “In this paper, we wanted to understand better how EDVs work at the molecular level and use that knowledge to improve them.”

In the new paper, Ngo, along with the Doudna lab team and collaborators, used a variety of techniques from molecular and structural biology to understand exactly which viral proteins are crucial to gaining entry into the cell and the cell’s nucleus, where DNA is stored. With a better understanding of the role of each protein, they were able to engineer minimal EDVs – these are EDVs where many of the viral proteins are removed, leaving only the ones that are crucial for delivering CRISPR components into cells.

Their data show that the minimal EDVs have improved editing efficiency relative to the previous generation EDVs. Another advantage of the minimal EDVs is that, with fewer components, they are easier and cheaper to make. The team are now testing whether reducing the number of viral proteins will also reduce the risk of harmful immune responses.

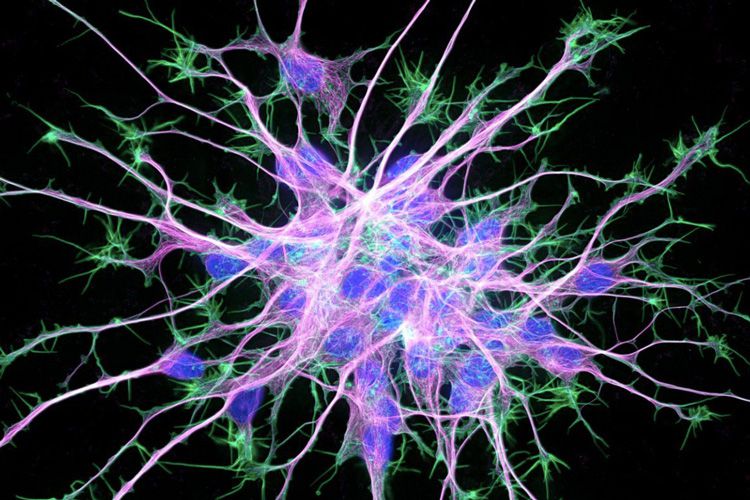

The ultimate aim of this work is to create therapies that can be used to directly edit cells inside patients’ bodies. Most current genomic therapies, like Casgevy for sickle cell disease or CAR-T immunotherapy for cancers, work by removing a patients’ cells from their body, editing them in a lab, and then putting them back in. But minimal EDVs have the potential to be used directly in patients.

“We’re really excited about the potential to make genome-editing therapies by simply giving patients an IV treatment,” says Ngo.

Currently, the team is collaborating with multiple labs at UCSF to create in vivo genome-editing treatments. Stay tuned!

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson