Meet an IGI Scientist: Basem Al-Shayeb

This series introduces the public and fellow researchers to our talented scientists. We interview different IGI members to find out who they are and what makes them passionate about science.

Basem Al-Shayeb is a Ph.D. candidate in the Banfield lab at UC Berkeley, where he uses metagenomics to uncover new microbes. He is working on a new IGI climate project, investigating how novel DNA elements affect methane-eating bacteria. He was recently named a 2021 “30 Under 30” by Forbes.

Where are you from?

I’m from Egypt. I was born in the US before my family moved back to Cairo and raised me there. I returned to the US for undergrad at the University of Minnesota. It was just a huge change for me with all the snow! After that, I came to Berkeley for grad school.

Do you have plans to go back anytime soon?

I’d love to visit soon, but it might be awhile with the current pandemic and vaccination rates.

Why did you become a scientist?

I’ve always been extremely passionate about discovering new things and asking a lot of questions. I’m very grateful that my school teachers cultivated my scientific curiosity, though secretly I think they may have found it both a blessing and a curse to have me in science classes because I would always ask so many questions beyond the scope of what was covered!

I didn’t know anybody who had a Ph.D. or did science as a career. I didn’t actually know that people did research and got paid for it. I went to undergrad thinking I wanted to be a doctor and help my community. Then I learned that you can do research as a career, and I could have a lot more of an impact than seeing patients day to day and get to fulfill my curiosity in biology.

In Minnesota, I got into synthetic biology through a flyer that was hanging on a wall in a building. It said something like, Would you like to engineer cells to do cool new things? I almost just passed by and didn’t take the information, but I decided to look into it. It was for a class that was run by Jeff Gralnick where we got to come up with new ideas that one could try to do in microbes. And I was fortunate that at U of M , they had an ‘active learning’ environment. Instead of traditional lectures, there was a lot of focus on reading and discussing research papers. With Jeff, I was able to lead an iGEM team researching our own ideas. Each of these experiences played a big role in my decision to apply to grad school after that.

What do you like to do when you’re not in the lab?

Me and Christine and other grad students used to go drawing around Berkeley. I do a lot of hiking and photography as well. I’m also part of a group of young scientists that translates the latest scientific findings to Arabic and holds conferences and panels to improve accessibility of science.

Do you have any funny memories of working in a lab or doing research?

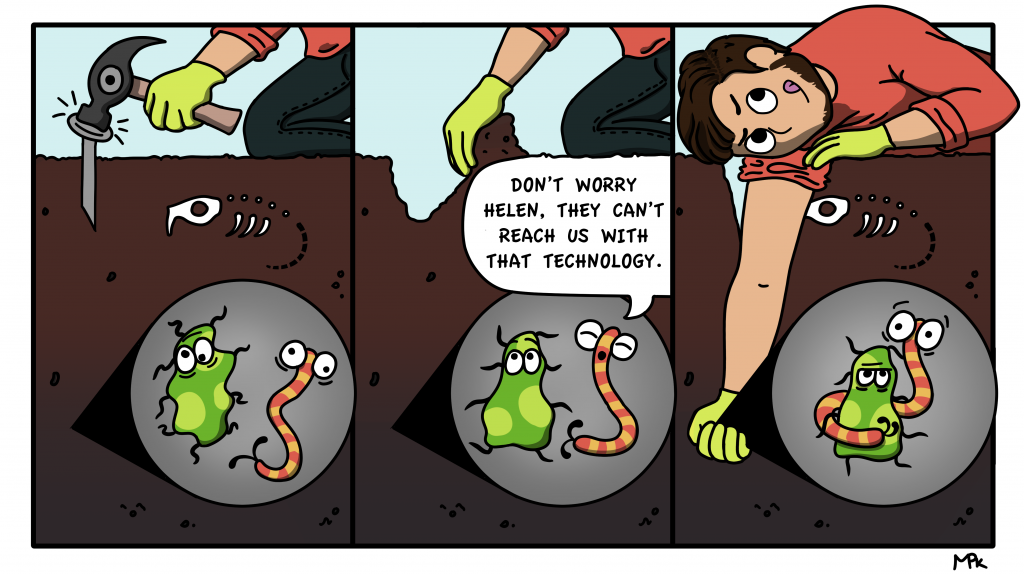

For my current research in the Banfield lab, we take soil samples, sometimes from deep in the mud, to learn more about microbes. We have to MacGyver our instruments to fit the sites where we’re doing it. And specifically for the work that turned into the Borg paper, I had really wanted some deep samples of microbes that don’t have access to oxygen because they’re so far underground.

I found this instrument that will hammer the metal tube we usually use for getting soil samples down into the mud, but it kept getting stuck. Eventually I had to dig my entire arm into the mud as deep as I could get it and just grab handfuls of mud.

What would you do if you weren’t a scientist?

I could see myself doing photography professionally.

What role does science play in the community?

I think people undervalue basic science and that’s something that needs to change! A lot of the big discoveries that I can think of did not come from testing a hypothesis – what we think of as the scientific method. A lot of things are discovered more sort of serendipitously because you’d never imagine how these things work until you discover them, like CRISPR or archaea.

The more I read about archaea, the more fascinated I get by them because they form this whole domain of life that is so understudied. The single most mind blowing thing to me was seeing a video that was in a supplementary dataset of a paper showing an archaeal cell that was Dorito shaped. It was triangular and it was dividing into three triangles!. We’re taught that cells will divide into two cells and that’s a very central part of biology.

If you don’t study these things out of curiosity, you’re just not going to get the sort of biotechnology that is useful.

What keeps you motivated and inspired?

I always think about, “How can this be useful for people?” Jennifer Doudna and Jill Banfield are my advisors and that’s a great combination. Jill is interested in basic discovery and Jennifer is always asking me, “So what? What can we do with this?”

In terms of people that I find inspiring there has only been one Nobel Laureate in sciences from the Middle East, Ahmed Zewail. To me, he was very inspirational because he came from the same town that my father came from. In Egypt, there is a tendency to think people from the Western world are just smarter, more hardworking, more capable. And they definitely have more resources.

Seeing that success in science is possible as exemplified by him was something that was very instrumental for me in being able to say, “Okay, maybe it’s not crazy of me to try and pursue a career in science.” Otherwise I would have just continued in medicine, probably. Now, I do as much as I can to present my work to people so that maybe I can inspire someone else to say, “It’s possible for me to do science too!”

Watch Basem discuss his recent publication on a mysterious DNA element:

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson