Meet an IGI Scientist: Alex Pollen

This series introduces the public and fellow researchers to our talented scientists. We interview different IGI members to find out who they are and what makes them passionate about science.

Alex Pollen is an Assistant Professor of Neurology at UCSF, and IGI’s 2020 SKCF Faculty Scholar. Learn more about his work on the genomic factors that make us uniquely human here.

Where are you from and how did you get into science?

I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts, outside of Boston. I was interested in evolution and my dad was a neurologist. As an undergrad at Harvard, I worked with Hans Hofmann who was studying cichlid fish brain evolution, which combined those two interests. After that, I did a Master’s degree in Oxford, studying comparative aspects of brain development with Zoltan Molnar, and then a Ph.D. with David Kingsley at Stanford. After that, I came to UCSF to do postdoctoral research with Arnold Kriegstein.

Why did you become a researcher?

E.O. Wilson lived in my town and I saw him give talks at the local library as a kid. I was always interested in evolution and in high school, the cloned sheep Dolly was in the news. People wondered if shorter telomeres on a cloned animal would reduce lifespan. And I wondered what happens to telomeres in really long-lived organisms.

When I was on a trip to California with my family, we saw big, old Redwood trees. I brought back needles and I wrote to some labs. I ended up doing a summer project with Matthew Meyerson, who had just started a lab at Dana Farber. Eventually, we got skin cells from Galapagos tortoises. We compared telomere length in eight year old and hundred year old tortoises. They had really long telomeres!

What do you like to do besides research?

As a parent of young children, when I’m not doing research, I’m in Golden Gate Park with my three and six year-old exploring different trails or the botanical garden and teaching them to ride bikes. There’s no other free time!

Describe a funny memory you have from your research.

I learned to scuba dive in the university pool to prepare for a field work trip to Lake Tanganyika in Tanzania. We were looking at the physical and social environment of cichlid fish, and seeing how this correlated with aspects of brain size and other aspects of trait evolution. We brought an air compressor and tanks on a 42-hour train ride and set up on this absolutely beautiful lake, the longest and second deepest lake in the world.

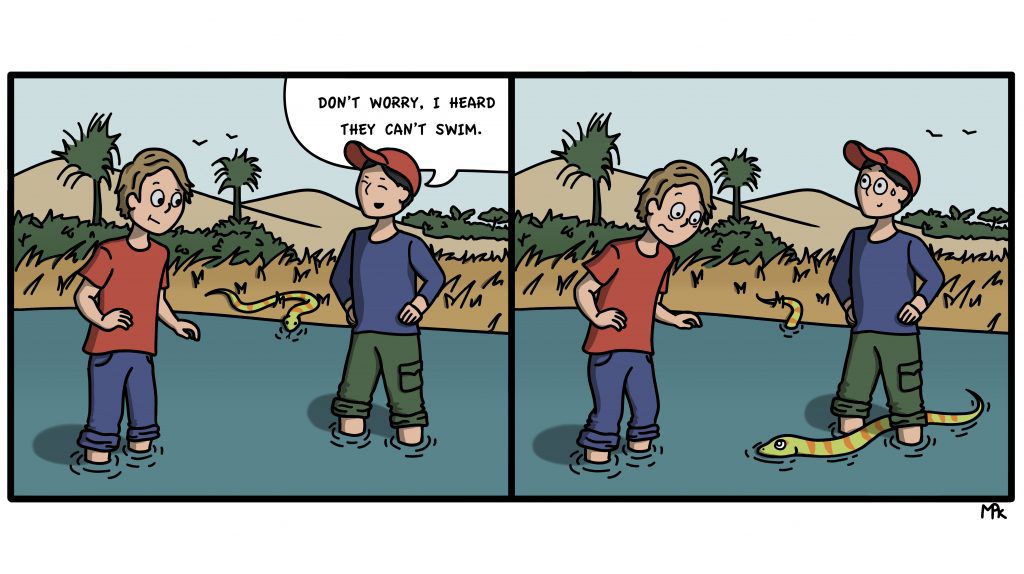

There are hundreds of species of cichlid fish in the African Great Lakes. They are like Darwin’s finches in terms of their adaptive radiation. It was such an incredible experience to pull up on the beach and have vervet monkeys come to the water. We were told that cobras can’t swim, but I saw one swim between my advisor’s legs.

It was like sticking my finger in a socket. It wasn’t too painful, but it was definitely a shock. I was surprised and excited, but we were all under water, so it was hard to tell people. I took my clipboard and I drew a picture of a fish and a lightning bolt.

I was studying brain evolution in these cichlid fish, but we were 10 miles from Gombe stream, the site of Jane Goodall’s field research. I really wanted to study human brain evolution and what makes us different from chimpanzees. We were asking these why questions about why do brain size changes happen in a certain way, but I wanted to get more at these mechanistic questions of how, which may be more tractable. And that’s what I’m working on now.

What would you do if you weren’t a scientist?

The current loss of biodiversity is tragic. I did a Master’s in environmental science and biodiversity conservation at Oxford. I would probably be applying that training to habitat conservation. Maybe I would be looking at more unorthodox ways. The loss of orangutan habitat for palm oil plantations is devastating. There might be a technology solution if one could design a cheaper palm oil alternative.

Tell us about someone or something that inspires you.

My dad was an inspiration. He was a neurologist and neuroscientist. His main interest was in studying the neural correlates of primary visual perception and consciousness, but he also treated patients and worked on Alzheimer’s genetics. He actually had a patient come in with a pedigree of what turned out to be early onset Alzheimer’s disease, and he traced the family back to a woman, Hannah, in the former Soviet Union. He traced her descendants, helping to map the disease-causing gene. Ultimately, he and his colleagues, led by Peter St George-Hyslop, mapped the family’s mutation to presenilin 1. He wrote a book, Hannah’s Heirs, about the family and the molecular genetics race.

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson