Wolf Prize Laureate Brian Staskawicz on 40 Years of Plant Immunity Research

IGI's Director of Sustainable Agriculture, Brian Staskawicz, was awarded the 2025 Wolf Prize in Agricutlure for key discoveries in plant immunity. The Wolf Prize in Agriculture, considered by many the Nobel Prize for agriculture, has been awarded annually since 1978 and carries a monetary award of $100,000.

What does the Wolf Prize mean to you?

The award recognizes my work alongside two of my close colleagues, Jeff Dangl and Jonathan Jones, for over 40 years of research into plant immunity. Our work began in the mid-1980s and continues to this day. Between the three of us, we’ve mentored numerous graduate students and postdocs who have gone on to establish their own labs and make significant contributions to the field. It’s an honor to receive this award, especially since plant pathology is often overlooked in such recognitions.

How did you become interested in plant pathology and immunity?

As an undergraduate at Bates College in Maine, I had a professor who connected me with a summer research opportunity at the University of Maine. I worked on Dutch Elm disease and saw firsthand how it had devastated elm trees across the U.S. That experience fascinated me—the interaction between organisms, their evolution, and how we might control them for the greater good.

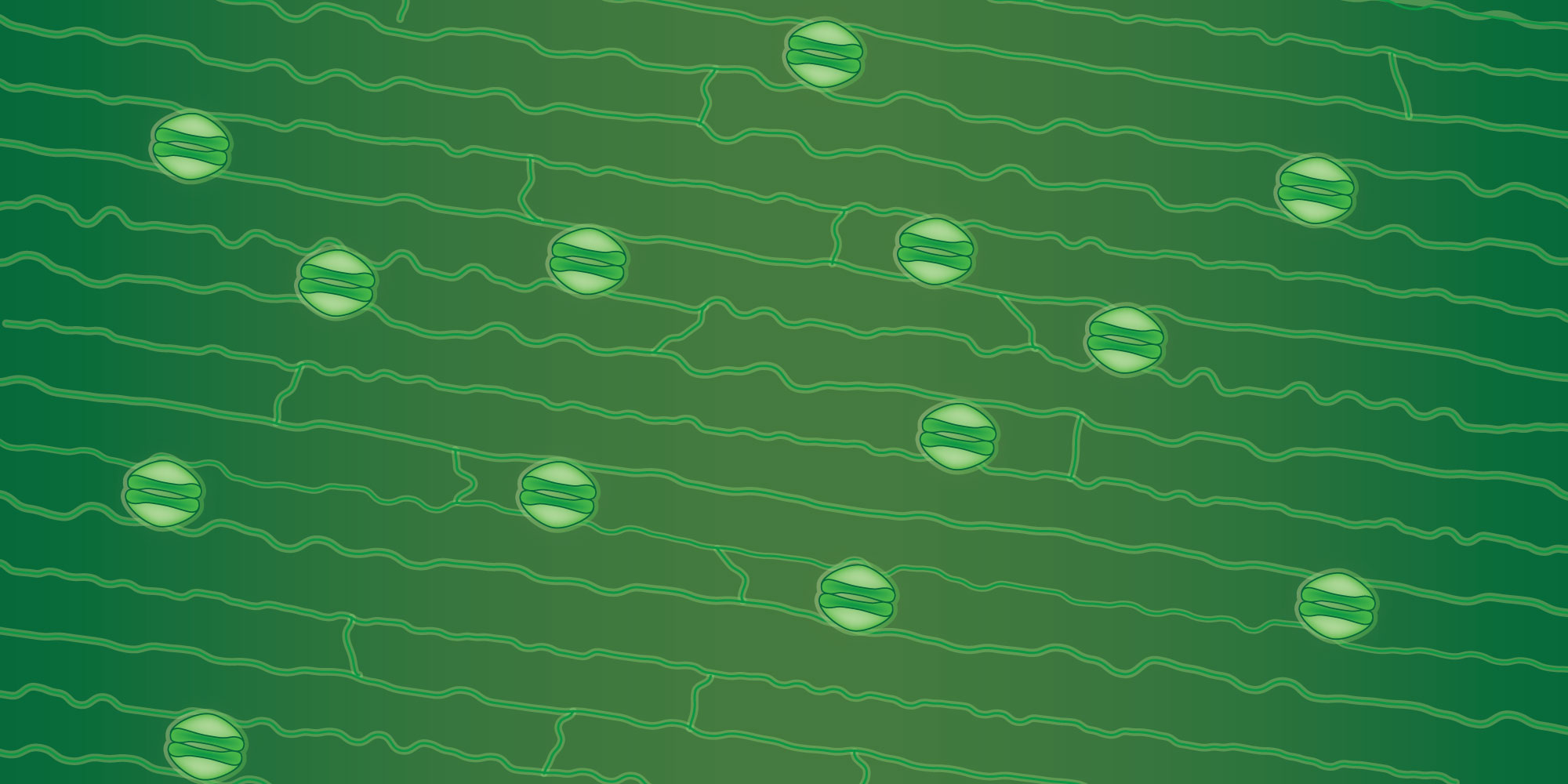

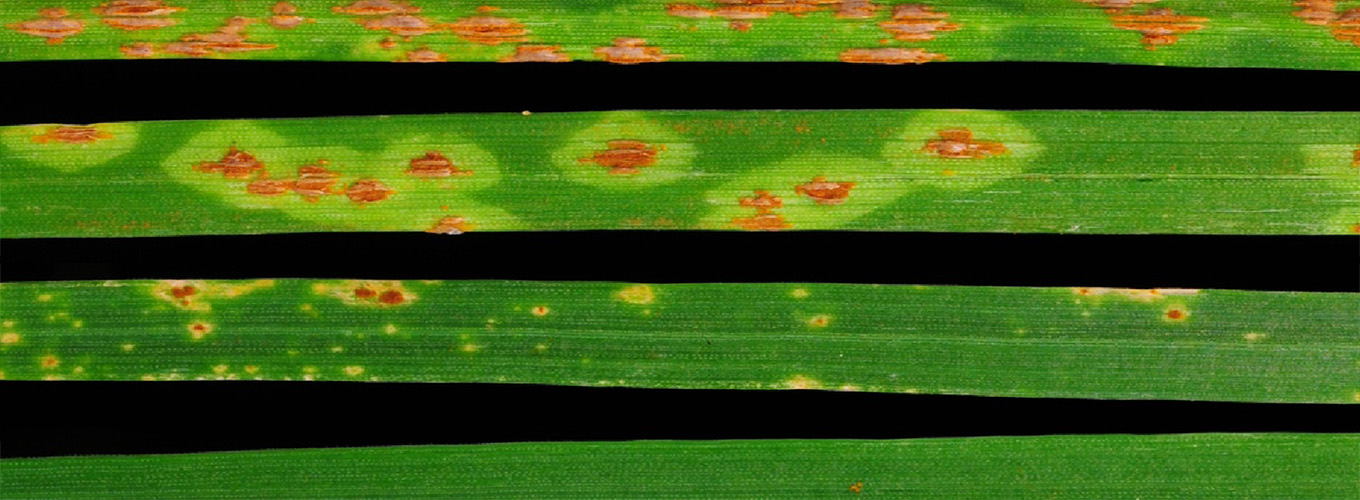

At Berkeley, we initially studied Arabidopsis but realized that to make a real impact, we needed to work with crop systems. Now, our research spans several agricultural crops, including rice, wheat, chickpeas, tomatoes, and cacao. My current focus at the Innovative Genomics Institute is using CRISPR to develop durable resistance to plant pathogens. With climate change, we are facing plant disease pandemics that threaten global food security. Sustainable solutions are crucial, as current disease control relies heavily on pesticides—a fossil fuel–driven industry that is both unsustainable and vulnerable to pathogen resistance.

What has kept you at Berkeley for most of your career?

I arrived at Berkeley for graduate school in 1976 and immediately thought, Who’s been hiding this place from me? No mosquitoes, no humidity, and a stunning landscape — it was an easy decision to stay.

My research has depended on federal grants from the NSF, NIH, USDA, and the Department of Energy. These grants not only fund our work but also support essential infrastructure, such as research facilities and operations staff. Even when philanthropy plays a role, federal funding remains indispensable.

Over nearly 50 years, I’ve seen many changes, but the current funding challenges are among the most concerning. My research has depended on federal grants from the NSF, NIH, USDA, and the Department of Energy. These grants not only fund our work but also support essential infrastructure, such as research facilities and operations staff. Even when philanthropy plays a role, federal funding remains indispensable. If research funding is cut, it will become increasingly difficult to sustain the level of innovation needed.

What projects excite you the most right now?

One project I’m particularly excited about stems from work by IGI’s Venkatesan Sundaresan, a previous Wolf Prize winner. He developed a method for cloning hybrid seeds, which allows farmers to save and replant seeds rather than purchasing new ones each season. This could be transformative, especially for farmers in low- and middle-income countries. While agricultural companies may resist this change, our goal is to benefit humanity.

These seeds also serve as a platform for introducing climate-resilient traits via CRISPR. I firmly believe — perhaps even convincing Jennifer Doudna now — that while CRISPR has great potential in biomedicine, its impact on agriculture will be even greater, affecting billions of people worldwide.

Another exciting project is in collaboration with Dave Savage at IGI and Savithramma Dinesh-Kumar at UC Davis. Currently, gene editing in plants requires working with plant cells in culture. We are developing a viral delivery system that introduces CRISPR directly into the reproductive cells of a mature plant, allowing its seeds to be gene-edited. This breakthrough would simplify plant genome editing significantly.

IGI thrives on interdisciplinary collaboration. In this project, Dave, a structural and synthetic biologist, works alongside virology experts from Davis. This kind of multidisciplinary approach is at the heart of IGI’s success.

Science feels like a hobby to me; I still wake up at 3 a.m. thinking about experiments.

What’s next for you?

I have the best job in the world. After retiring from my previous role at Berkeley, I now hold an appointment as a professor of the graduate school, which means I no longer have teaching or administrative duties—I can focus entirely on research. Science feels like a hobby to me; I still wake up at 3 a.m. thinking about experiments.

What advice would you give to young people interested in plant biology?

If you’re passionate about it, go for it. Federal funding is under threat, which makes things challenging, but I’m an optimist. I believe these challenges will eventually resolve, and the need for innovative plant biology will only grow.

Read more:

- Brian Staskawicz awarded Wolf Prize in Agriculture – Rausser College of Natural Resources

- Wolf Prize Award Citation

- The plant immune system: From discovery to deployment – Cell

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson