Reimagining Women in STEM Gallery

Portrait Gallery

Reimagining Women in STEM

In this gallery, women who have made remarkable contributions to STEM fields are placed in famous works by Western artists. By putting scientists in the place of the portrait subjects, we position them as deserving of attention or even revery. These colorful reimaginings are meant to catch the viewer’s eye, compelling them to look more closely and reconsider prior assumptions.

About the artist

Kaylene Son is a second-year undergraduate at UC Berkeley, studying Media Studies and pursuing the Berkeley Certificate in Design Innovation. Kaylene previously worked in graphic design and illustration positions at Checkr and Indeed, developing branding guidelines and visual mock-ups. Kaylene works with the IGI to create illustrations, with special attention to researchers from underrepresented groups. Learn more about Kaylene here.

Click to read more about each scientist.

Meemann Chang

Meemann Chang (born 1936) is a Chinese paleontologist, best known for her studies of how aquatic animals adapted to life on land. She studied for her undergraduate degree in Russia before returning to China to work at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology in Beijing. In 1966, during China’s Cultural Revolution, she was imprisoned in a labor camp for almost 15 years. After her release, she was determined to continue her research career. She traveled to Stockholm to earn a Ph.D., and upon returning to China, became the first woman to lead the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology.

It became clear to Chang that Chinese science had fallen behind during the Cultural Revolution. She and her colleagues began working to translate books and research papers from English to make accessible the resources that young researchers needed to be competitive in the field and advance the field of paleontology in China. At the same time, Chang continued her own research focused on how, across evolutionary time, fish migrated to land. Her pioneering fossil discoveries changed how the field conceived of this unique moment in evolution. A species of fish, dinosaur, and two birds are named for her.

She was elected president of the International Paleontological Association in 1992, and of the Paleontological Society of China in 1993. In 2016, she was awarded the Romer-Simpson Medal, the highest honor given to a paleontologist. Here she is pictured in the style of French Impressionist Claude Monet’s “Woman With a Parasol.” Click here to open full-sized image

Katherine Johnson

Katherine Johnson (1918 – 2020) was an American mathematician, famous for her work on spaceflight. Johnson, a Black American woman, grew up in the segregated South. She completed her bachelor’s degree in Mathematics at age 18 with the dream of becoming a research mathematician. She earned her Ph.D. as one of the first three Black Americans, and the only woman, to be admitted into the graduate program at West Virginia University.

Throughout her career, Johnson continued this pattern of trailblazing. She began working for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which would later become part of NASA, as a so-called “human computer” in the 1950s when they were still segregated and had only just begun to hire women. Despite discrimination, she quickly became known for her extraordinary mathematical abilities. Johnson’s work with NASA included calculating trajectories, launch windows, and return paths for the first US space missions, including the Apollo 11 moon mission and the Space Shuttle program. In 2016, President Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor that can be given to a civilian. Her life and work are celebrated in the popular movie “Hidden Figures” (2016). In this illustration, Johnson is portrayed in the style of American pop artist Andy Warhol’s famous colorful offset prints of Marilyn Monroe. Click here to open full-sized image

Rita Levi-Montalcini

After World War II, the family returned to Turin and Levi-Montalcini got a fellowship studying with Viktor Hamburger at Washington University in St. Louis. Her publications with Levi conflicted with Hamburger’s research, and he was curious to see the work replicated in a formal lab set up. Levi-Montalcini stayed at Washington University doing research for 30 years, becoming a full professor in 1958. During her time there, she isolated nerve growth factor (NGF), a peptide crucial for nerve cell growth and the first of many cell growth factors that scientists would find. NGF is crucial not only for the developing nervous system, but Levi-Montalcini identified that some cancerous tumors cause rapid nerve cell group growth, taking over neighboring tissues. She suggested that the tumors themselves were able to produce NGF as part of their growth strategy. In 1986, Levi-Montalcini would be awarded a Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for her research on NGF.

Her career went on to include heading neurology and cell biology research centers in Italy, research on mast cells in disease processes, and being appointed a Senator for Life by the Italian president in 2001. In this image, she is rendered in the style of Jewish-Polish painter Tamara de Lempicka’s “Young Lady with Gloves.” Lempicka survived the Holocaust by fleeing to the US in the late 1930s. Click here to open full-sized image

Ada Lovelace

Ada Lovelace (1815 – 1852) was an English mathematician — or, “enchantress of numbers” according to her colleague Charles Babbage. Babbage envisioned a general-purpose mechanical computer that he called the Analytic Engine. Lovelace translated the description of his engine and wrote her own set of notes on it. These notes turned out to be three times longer than the strict translation and contained her own ideas about what the Analytical Machine could potentially do, including a draft of the series of operations to solve complex math problems. Many people consider this to be the first computer program. While Babbage focused on using the Analytical Engine to do math, Lovelace theorized that such a machine would be able to manipulate not only numbers, but any symbols with sets of rules.

In 1953, 110 years after her notes were originally published, they were republished and started getting new attention just as the first real computers were being built. Only then did it become apparent just how ahead of her time she was. Here, she is portrayed in the style of Czech artist Alphonse Mucha’s lithograph “Daydream.” Click here to open full-sized image

Wangari Maathia

Wangari Maathia (1940 – 2011) was a Kenyan environmental activist and champion of women’s rights. Born on a farm in the highlands of Kenya, Maathia earned a master’s degree in Biology in the United States and then a Ph.D. at the University of Nairobi in Kenya in 1971, becoming the first woman in East and Central Africa to earn a Ph.D. As a professor at the University of Nairobi, she campaigned for equal benefits for women employees. She got involved with the United Nations Environmental Programme and the National Council of Women in Kenya. In her work with these organizations, she began to see a reciprocal relationship between environmental degradation and poverty, and the fact that political power was concentrated in the hands of the few. She heard from women in rural Kenya about their water sources drying up, their food supplies being compromised, and reduced access to wood for fuel and building as a result of deforestation. In response, she founded the Greenbelt Movement in 1977, to help teach rural women to grow saplings of native trees. The Movement then purchases the saplings and plants them as part of their reforestation efforts — which has contributed to the planting of over 30 million saplings in Kenya and beyond. The Greenbelt Movement expanded to include civic and environmental education, small loans for rural women, beekeeping, and global advocacy to fight climate change.

Maathia believed that environmental struggle was intertwined with the struggle for true democracy, and she advocated fiercely for both, including going on a pro-democracy hunger strike. In the early 2000s, after over two decades of her pro-democracy protests, she was elected to the Kenyan Parliament, worked in the Ministry for the Environment, and founded a political party supporting the Greenbelt Movement and environmentalism. In 2004, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Here, she is portrayed in the style of Austrian painter Gustav Klimt’s “Adele Bloch-Bauer I.” Klimt’s vibrant geometric shapes are reminiscent of the patterns of Maathia’s kitenge dresses and headscarves. Click here to open full-sized image

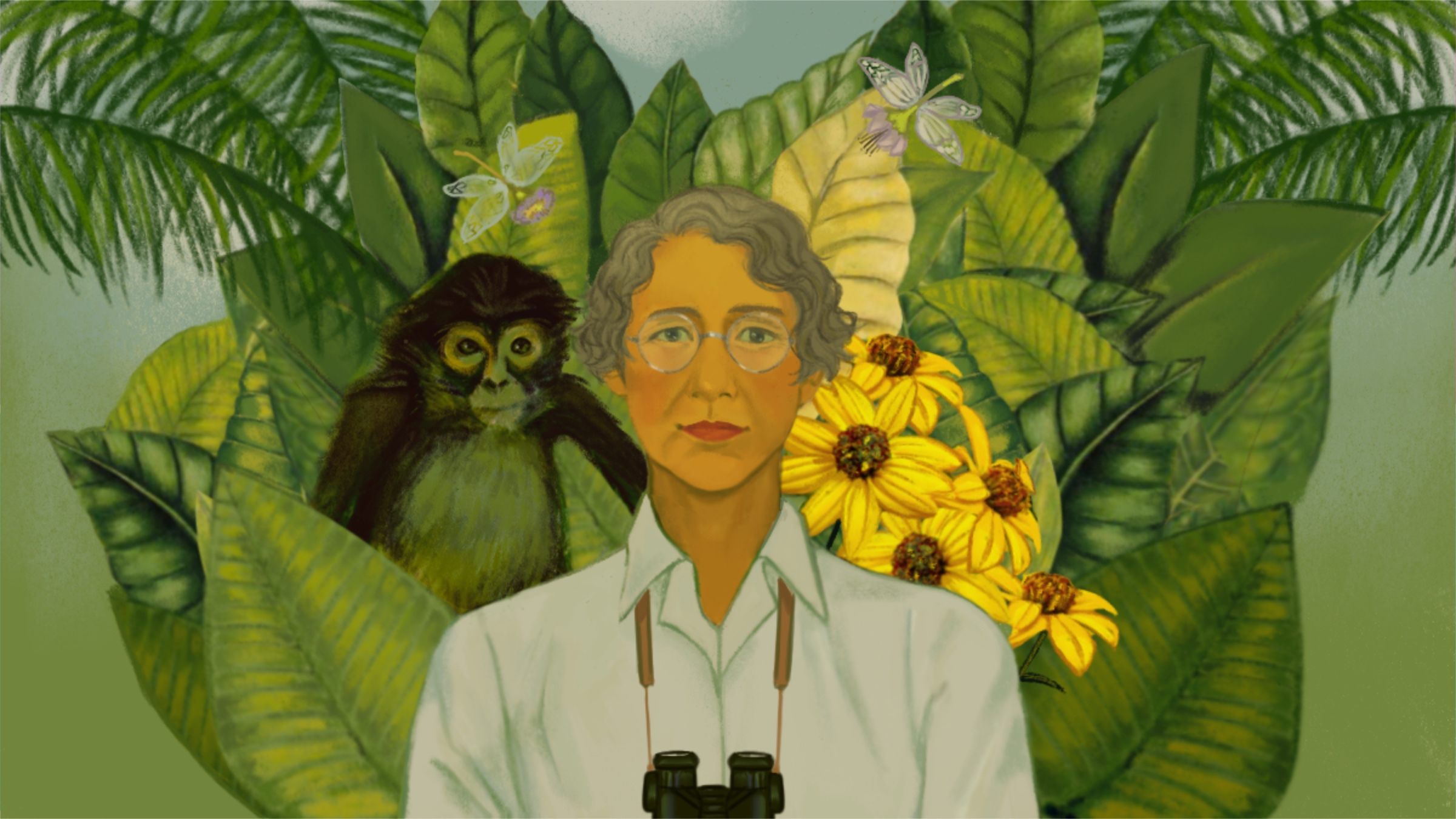

Ynés Mexia

Ynés Mexia (1872 – 1938) was a Mexican-American botanist. Born to a Mexican father and American mother, she spent her early years in Texas and Mexico. As a young adult, she ran her father’s ranch in Mexico. But after a failed marriage and financial difficulties, she experienced a mental health crisis and moved to San Francisco for treatment. In San Francisco, she got involved with the budding environmental movement, going hiking and camping with the Sierra Club and Save the Redwoods, as well as in activism promoting national parks. These interests led her to start pursuing a degree in Natural Sciences at UC Berkeley in 1921, at the age of 51 — something that was unheard of for a woman of her age at the time. In her courses at UC Berkeley, Mexia discovered botany and her love of collecting plants.

In 1925, Mexia went on her first plant collecting trip to Mexico with a group of botanists, but quickly realized she could be more efficient on her own. Thus began her career traveling all over the American continents, from what would come to be known as the Denali National Park in Alaska to Tierra del Fuego at the southernmost tip of Argentina, collecting specimens for museums, herbaria, and private collectors. During her 13 year career as a collector, she preserved more than 145,000 specimens, discovered a new plant genus and over 500 new species, 50 of which were named for her, including the yellow Mexianthus mexicanus pictured in this illustration. This illustration is a nod to Mexican painter Frida Kahlo’s “Self Portrait with Monkey.” Click here to open full-sized image

Burcin Mutlu-Pakdil

Burcin Mutlu-Pakdil is a contemporary astronomer who was born in Turkey in the 1980s and is known for her discovery of a new type of galaxy. The first person in her family to go to college, she studied for her undergraduate degree at Bilkent University in Turkey. In her time there, she encountered gender-based discrimination and was banned from wearing the hijab that is part of her expression of her Muslim faith. After completing her undergraduate degree, she moved to the United States to pursue a Ph.D. in Astrophysics at the University of Minnesota. While studying in Minnesota, she discovered a galaxy with an extremely unusual shape: double ringed and elliptical. This finding challenged accepted ideas of how galaxies form and evolve.

Since then, Mutlu-Pakdil worked at the Steward Observatory in Arizona, the University of Chicago, and is now a professor at Dartmouth University, where she uses large telescopes like the Hubble and Magellan to observe galaxies and supermassive black holes. She is focused on understanding the nature of dark matter and galaxy formation.

Mutlu-Pakdil works with the American Astronomical Society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and other professional groups to promote inclusion of women and other marginalized groups in STEM. In this portrait, she is pictured in the style of Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer’s “Girl With the Pearl Earring,” with the pearl earring reimagined as a hijab pin. Click here to open full-sized image

Roseli Ocampo-Friedmann

Roseli Ocampo-Friedmann (1937 – 2005) was a Filipino botanist and microbiologist, famous for finding microorganisms that could live in extreme environments. As a child, she was fascinated by plants. She studied at the University of the Philippines, receiving a degree in Botany. At Hebrew University in Israel, where she went to do study for her master’s degree, she met her future husband and scientific collaborator Imre Friedman. A couple years earlier, Friedman had discovered that microscopic algae and photosynthetic bacteria could grow under the surface of rocks. Ocampo-Friedman figured out ways to grow these unusual organisms in the lab so that they could be studied.

Ocampo-Friedman and her husband later moved to Florida, where she obtained her Ph.D. and then became a professor at Florida A&M University. Friedman and Ocampo-Friedmann worked together closely for decades, traveling to remote, hostile environments to look for life. They discovered cryptoendoliths: microorganisms that live in an arctic mountain range previously thought to be lifeless. These organisms can tolerate the cold, and in the summer, rehydrate and photosynthesize. Ocampo-Friedman and her husband would go on to find microorganisms living under the frozen ground in the Far North and in the Siberian permafrost. In all, she discovered more than a thousand microorganisms that could live in extreme environments, and her remarkable ability to grow them in laboratories has enabled researchers to study their biology.

Her research influenced NASA’s thinking about the possibilities for life in seemingly hostile environments like Mars. In the later part of her career, Ocampo-Friedman worked as a researcher for the SETI Institute, an offshoot of NASA’s research into the search for extraterrestrial life. In this illustration, Ocampo-Friedman is pictured in the style of street artist Banksy’s “Balloon Girl,” the red balloon replaced with a string of microbes. Click here to open full-sized image

Helen Rodríguez Trías

Helen Rodríguez Trías (1929 – 2001) was a Puerto Rican physician and relentless advocate for women’s and children’s healthcare. Rodriguez grew up between New York City and San Juan, earning her bachelor’s and medical degrees from the University of Puerto Rico. In the 1970s, she set up the first center for infant care in Puerto Rico, reducing mortality by 50 percent within just a few years.

As a physician, she gained a profound understanding of how the social environment, particularly poverty and racism, affect the health of individuals and communities. During her time in Puerto Rico, she became aware of the widespread practice of permanently sterilizing women without their consent. This practice, which grew out of the eugenics movement, was also common in the American South, where Black women, poor women, and women with disabilities were targeted. Rodríguez Trías was the cofounder of the Commission to End Sterilization Abuse and drafted a set of guidelines for informed consent that was adapted by the FDA. She saw reproductive decision-making as central to women’s self-determination, and also co-founded the Coalition for Abortion Rights.

Rodríguez Trías moved back to New York City in the 80s, where she was the head of pediatrics at the hospital in the Bronx. In her work there, she helped increase understanding of public health and community concerns among the staff and the Black and Latinx clients they were serving. In the 1980s, she led New York State’s AIDS Institute, bringing focus to how the HIV/AIDS epidemic was impacting women of color. Later, she was appointed head of the American Public Health Association, serving as its first Latina president. In 2001, she was awarded the presidential Citizens Medal for her work serving individuals who were HIV-positive. In this illustration, she is portrayed in the style of Spanish painter Pablo Picasso’s “Portrait of Dora Maar.” Click here to open full-sized image