The project aims to show how CRISPR can help potato farmers put more food on the table and stop viruses that threaten crops.

If you’ve ever had a potato sit too long on your kitchen counter, or if you’ve seen how Matt Damon’s character survives in The Martian, you will understand how easy it is to grow more potatoes from just one potato. Certain crop plants like potatoes don’t need to be grown from seeds, they can grow clonally from the edible root part, known as the tuber. According to Imtiyaz Khanday Assistant Professor of Plant Sciences at UC Davis, while growing potatoes from tubers is easy, it is also a problem for farmers — and CRISPR could provide the solution.

The recipient of the 2021 Shurl & Kay Curci Foundation (SKCF) Faculty Scholars Program award at the IGI, an award that supports early-career faculty with bold ideas for cutting-edge research that pushes the boundaries of genomics, Khanday is developing new methods of propagating potatoes clonally, but using seeds.

“Potatoes are normally grown from tubers. You cut a potato in half and just plant it, and that’s how you grow them. We’re essentially burying 10% of the edible food into the ground by planting these tubers,” says Khanday.

Tuber planting has several other disadvantages, including transmission of viruses and other pests. By using tubers, viruses that infect the plant in one generation will accumulate over time. Viruses that attack potatoes can wipe out crops and threaten a critical source of nutrition and income for many communities.

There’s a key reason that farmers use the tuber method: it lets them control the variety of potato they grow. There are over 4000 varieties of potato, and farmers want to grow specific, preferred varieties. When you grow a potato from a tuber, you get a clone of the parent potato. When you grow from a seed, you get a mix of genes from two plants.

“The potato has a highly heterozygous genome, meaning if you plant it from seeds, almost every seed gives rise to a different variety of potato. But if you can make seeds that are clones of the mother plant then you can circumvent this problem,” says Khanday.

Some plants do this already through a phenomenon called “apomixis” where viable seeds are produced asexually, without the need for fertilization. Each seed is an exact copy of the mother plant. But apart from some citrus fruits, no major food crops naturally reproduce this way.

“The potential of this form of reproduction has been known for a long time and a lot of research went into this for over four decades. The last three decades have been really intense, trying to harness this natural way of clonal reproduction to enable us to propagate crops — but nothing ever worked.”

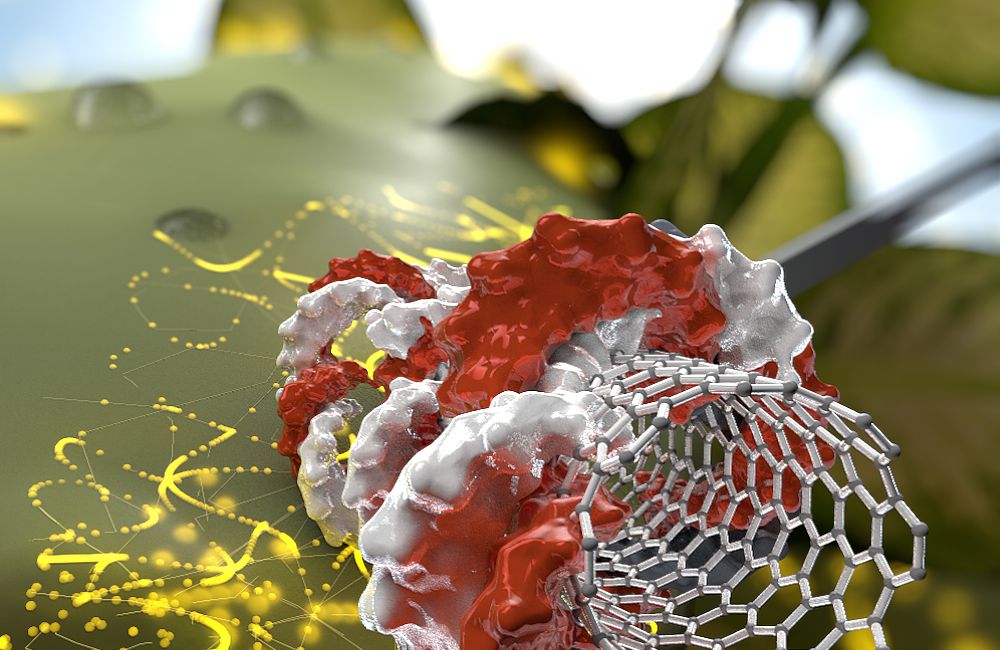

Khanday is optimistic that CRISPR holds the key to a new, improved potato based on previous work in rice where CRISPR genome editing was able to successfully activate apomixis by activating a gene in egg cells called BABY BOOM that would normally come from sperm.

“If we express this gene in the egg cell, where it isn’t normally expressed, you can just completely do away with the sperm cell and make an embryo from the egg cell itself,” explains Khanday.

Rice and potatoes are not closely related plants — one is a grass, the other is a nightshade — so the first step for Khanday is to confirm that what works in rice still holds true in potatoes, work that is now possible thanks to the SKCF award and the opportunity to collaborate with other IGI Investigators.

“When it comes to potatoes, we’re basically taking an educated guess and thinking that this pathway works exactly the same way. We will have to do the experiments, prove that it does, and then it can proceed ahead,” says Khanday.

If all goes to plan, the result will be a potato — in fact any variety of potato — that can be replanted from seed, and retain its characteristics from year to year. This would stop food waste, eliminate viruses that are carried in the tubers, improve the health of farming communities, and put money back in farmers’ pockets.

“In some of the developing countries, the new tubers that the farmers buy each year correspond to up to 40 percent of the production cost. That will come down drastically with seed propagation,” says Khanday. “You can just save a little bit of seed from the previous year and use that for propagation next year. It will be essentially the same hybrid variety that you grew previously.”