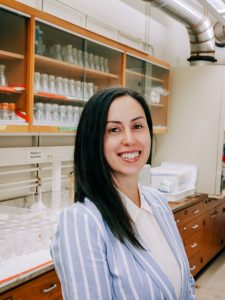

Meet an IGI Scientist: Veronika Kivenson

This series introduces the public and fellow researchers to our talented scientists. We interview different IGI members to find out who they are and what makes them passionate about science.

Veronika Kivenson is a 2022 Tory Burch Fellow at the IGI. She studies microbial genomes and is developing microbe-inspired therapeutics. To come to our February 2023 open house for an additional entrepreneurial program supporting gender equity in biotechnology, RSVP here.

WHERE ARE YOU FROM?

I was born in Ukraine and I moved to the United States when I was five.

WHY DID YOU BECOME A SCIENTIST?

I was always curious about how things work, about nature and technology. I grew up

You’re our second Tory Burch Entrepreneurial Fellow. Give us a brief overview of the project you are working towards launching a company with.

For my Ph.D., I studied toxic waste in the ocean. I was interested in marine microbes and if they can be helpful in dealing with that toxic waste. One way to get to know the microbes is to look at their genomes. That tells you who they are and something about what they do. While I was studying their genomes, I found that microbes have a mechanism to change how they interpret their genetic code depending on the environment. When I do science, I’m just like a kid asking, “Why?” And then asking it again and again, digging in further.

What it led to is that microbes could be used for human health purposes. So I wanted to do something with that – I didn’t want this just to be data in my notebook, but something that I could one day use to hopefully help people. The way you turn a discovery into a real product that helps someone is through entrepreneurship.

When I saw Tory Burch Fellowship, it was just the exact description of where I was and what I wanted to do. I was so excited I couldn’t sleep! And when I found out that I had gotten it, it just blew me away that people really believed that I can do this. It’s amazing to have all these resources and be able to be dedicated to it full time.

WHAT DO YOU LIKE TO DO BESIDES RESEARCH?

I’m obsessed with scuba. I actually first learned it through a gym class at Mount Holyoke. It was really hard and I wasn’t very good at it at first. I wasn’t sure if I should even try to get certified. And my friend told me, “Maybe you’ll succeed and maybe you won’t. You can still go not knowing the outcome. It’s okay to go and to fail…”. And it sounds so simple, but it blew my mind. If I don’t succeed, that’ll still be okay.

So I took extra classes and got certified. I fell in love with it and I’ve been diving for a decade now. The ocean feels like the truest wilderness that there is because there are no fences or barriers – it just feels kind of infinite. In California, I love diving in the kelp forests. I’ve also explored sunken shipwrecks, and have been diving for work.

As a researcher, I collected samples underwater at an oil spill from a ruptured pipeline just north of Santa Barbara.

WHAT WOULD YOU DO IF YOU WEREN’T A SCIENTIST?

I like teaching, outreach, and just connecting with students. But I can’t really imagine doing anything besides research! I feel super lucky to be able to do it, and it’s all because of the opportunities I had that started at community college.

Is there anything else you want to tell people?

I think a lot about who gets to be a scientist and who doesn’t and what my path looked like. My older brother helped me a lot – he was working on his PhD and tutoring me when I was taking science classes. He helped me with applying for internships. He was an excellent resource and support, and I was really privileged to have that. And many people don’t have that, and we see that disproportionately, the people who become researchers have parents with advanced degrees.

The systems that are in place for becoming a scientist just aren’t designed for fairness. There are a lot of programs to help individual students and those are really valuable, but one of my dreams is to completely change the system so it doesn’t systematically exclude certain groups of people.

I don’t know yet what that would look like. One idea that I have is inspired by Bunker Hill Community College, which is committed to having open admissions – they literally accept everyone with a high school diploma or GED. My far-fetched idea is to create the equivalent of that for research for undergraduates: completely open, and available on a large scale. We pay people to do research and support them as they learn, and then the rest is self-selection: the people who want to do it will keep coming back and learning, and the people for whom it’s not a good fit will find something else – you could keep going as far as you want.

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson