Meet an IGI Scientist – Rohan Sachdeva

This series introduces the public and fellow researchers to our talented scientists. We interview different IGI members to find out who they are and what makes them passionate about science.

Rohan Sachdeva is the IGI’s Director of Computational Infrastructure. Rohan manages the IGI’s advanced computational systems and uses them to study microbes and viruses in close collaboration with the Banfield lab and BIOME.

Where are you from?

I was born in Omaha, Nebraska, and lived in Dodge City, Kansas, until I was four. I’m a first gen immigrant — my parents moved there from India. My dad’s a veterinarian, and they would not give veterinary licenses to foreign-trained veterinarians in Kansas then so we moved to Los Angeles, and I grew up there.

Why did you become a scientist?

Like many other scientists, I have always been interested in how things work. I majored in biology and minored in history, and I thought of going to med school. My parents are physicians, and there was a lot of pressure as a first-gen immigrant to pick a “prestigious” career.

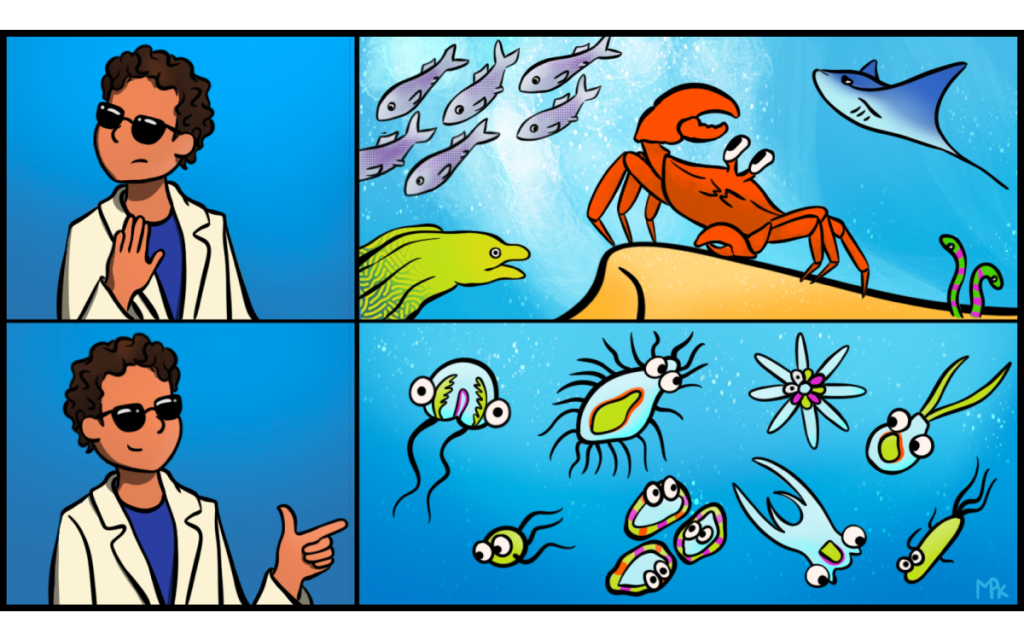

I was seeking faculty to do research to add to my credentials, and it just happened that one of the professors that responded was a marine microbiologist. Back then, I thought that meant going out, diving, and counting fish or coral — that kind of thing. I had no conception of microbes in the environment.

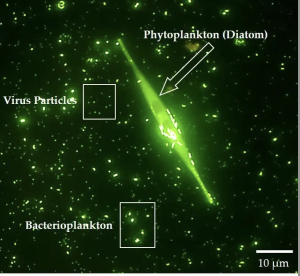

My first project focused on marine bacteria and marine viruses. I would take ocean water samples with a bucket, make slides, and look at them on a microscope. It looks like you’re looking at a bright field of stars — almost as if you’re looking at the Milky Way. It’s all green, and the bacteria are blob-like, while the viruses are little pinpricks.

I fell in love with the idea that there’s this whole world that we can’t see and still don’t know much about.

I remember being on one of my first research vessels — you can see right through seawater, yet there’s this hidden world in it. And this isn’t just the ocean. In soil, your gut, on your tabletop, and even your toothbrush. It’s mind-blowing to me.

I’ve also always been a computer geek my whole life. I have always loved building computers. And computation analysis has become a central aspect of studying the microbial world. It became this nice confluence where I got to have this fun with computers and combine it with science.

What is your science about now?

Currently, my research is about discovering and understanding unknown microbes. For example, a teaspoon of ocean water has about 5 million bacteria. It’s teeming with life. A big part of my research is analyzing their genetic material and seeing what it can tell us about their functions in their environments. Do they have genes involved in photosynthesis, for example?

What do you like to do besides research?

My significant interest right now is working on cars. I have this 22-year-old convertible that I work on. I bought it off Craigslist once I graduated with a Ph.D. as a present to myself.

I have this romantic idea that I would be like a car mechanic to store and repair old, vintage cars. I’ve always been a person who’s into fast stuff and loved cars. I grew up in a part of the city that is, I think, one of the capitals of LA street racing. It’s like what Fast and Furious is based on. As I’ve gotten older, there’s also the art side of cars. It’s why I appreciate vintage cars more— their art and creativity. They’re also a testament to the engineering and creative abilities of humans that we can see and experience every day.

Do you still watch the Fast and Furious movies?

I do. It’s a guilty pleasure, especially the first movie.

Do you have any funny memories of doing research?

Here’s a recent one: I was with Jill Banfield and a postdoc in Jill’s lab, Marie Schoelmerich. We were taking samples from a seasonal wetland in Mediterranean climates. They fill up in the winter when it rains and then dry out. They’re an essential environmental system that hosts organisms adapted for that lifestyle. and they’re a hotspot of bio biodiversity.

We were sampling directly around the wetland to get some of the soil. As we collected samples, Jill warned me, “Don’t go too near the boggy part of it.” I have been sampling like this for years, so I think I had some hubris. I thought to myself, “Yeah, okay… I know what I’m doing.”

My foot went straight into the bog — up to my waist. I was trying to pull myself out, but I couldn’t, and I didn’t want to tell anyone out of embarrassment. I finally had to give in. Jill had to take a shovel and dig me out. I had to pull my shoe off — it got stuck, and we had to dig it out separately.

What do you think is one thing scientists can do to make a difference in the world right now?

I think that doing science for the sake of it is essential. Sometimes there is a little push that there needs to be a practical result from the research. But understanding the natural world is a goal in and of itself, and I hope we don’t lose sight of that.

What inspires or motivates you?

The world around us. Whenever I walk around, I think about how things work and the interplay between organisms and their environments. As time goes on, I’m appreciating it even more.

Any advice you’d like to give to other scientists?

My advice is to try and mix what you love with your science. In the past I sort of avoided that, thinking that I didn’t want to make a career out of what I enjoyed. Computers were a hobby of mine, and biology, which I loved, was separate. However, I was able to combine those two aspects into my current career, and I enjoy it. So, if you can find a way to put your passions into science, that will make everything go a lot more smoothly.

Also, follow the serendipitous opportunities. Keep your mind open. That’s how I fell into this field, and it’s been great for me.

You may also be interested in

IGI Seminar Series: Progress and Challenges in Delivering Cassava with RNAi-mediated Resistance to Cassava Brown Streak Disease to Smallholder Farmers in Africa – It’s Not Just About the Technology

IGI Seminar Series: Empowering Teachers, Transforming Classrooms: Advancing K-12 STEM Education

IGI Seminar Series: Writing DNA with RNA: Genome Engineering by Target-Primed Reverse Transcription

By

Héctor L. Torres Vera

By

Héctor L. Torres Vera