Meet an IGI Scientist: Matthew Kan

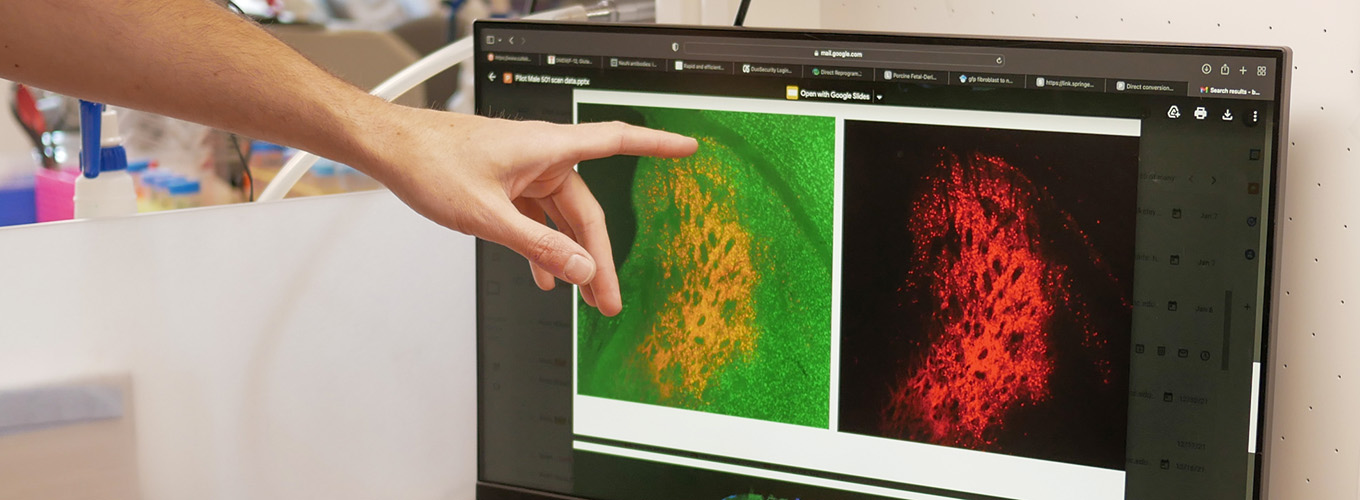

Matthew Kan is an IGI Investigator and an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at UCSF. He specializes in clinical immunology and, alongside Jennifer Doudna and Jennifer Puck, he is developing CRISPR-based therapies for patients with inherited immune deficiencies.

Where are you from?

I was originally born in New York, but I grew up in the Bay Area in Danville. I lived on the East Coast for 13 years and moved back to the Bay Area in 2016.

How did you become a physician-scientist?

At the end of high school, Pattie Carothers, my AP biology teacher, encouraged me to apply to a program at Stanford to get high school students and undergraduates into research, specifically immunology. Once accepted into the program, I chose the lab of Dale Umetsu, a pediatric physician-scientist trying to better understand asthma. It was my first time in the lab and helped me to understand how science works. My first direct mentor in the lab was Everett Meyer, a then M.D.-Ph.D. student who is now a bone marrow transplanter and lab investigator, so I got a double dose of this physician-scientist exposure, and that’s how I realized, oh, this is a cool career where research can be developed into therapies.

I did my undergrad at Harvard, then my M.D. and Ph.D. in immunology at Duke University in the labs of Dee Gunn and Carol Colton. I did a short postdoc with Atul Butte at UCSF in health informatics. Then I completed my residency in pediatric medicine and my clinical fellowship in allergy and immunology at UCSF. I am now an early career clinical immunologist on a physician-scientist path mentored by Jennifer Doudna, who is famously a co-discoverer of CRISPR genome editing, and Jennifer Puck, a clinical immunologist who identified many of the genetic defects that cause primary immunodeficiencies and invented the newborn screen for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID).

What would you do if you weren’t working in STEM?

I’m also a violinist, so I would have loved to become a chamber musician playing in the quartet. A lot of my musical peers when I was young are now well-established classical musicians. I’ve had, and continue to have, a lot of really amazing musical experiences, so I consider myself very blessed.

Could you describe an experience that left a lasting impression on you?

The UCSF Division of Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Bone Marrow Transplant does an annual outreach to Navajo Nation. People of Navajo and Apache descent have the highest incidence of Artemis-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) in any human population. Our group has been caring for patients in the area with SCID for almost 40 years.

Last year we visited the first patient who ever got lentiviral gene therapy for Artemis-SCID. It was really meaningful to see where he lived and grew up and see that he’s healthy now and doing quite well. So, while we hope that CRISPR will help us make an even better therapy, it’s pretty amazing to see how well the first version of gene therapies work.

What’s the biggest challenge in your field?

A really big problem in the field is that genetic and cell therapies are expensive. There was a medicine that was just approved for $4.5 million per patient, and I don’t think that’s a sustainable path. As Jennifer Doudna has stated many times, accessibility of treatments is crucial. I don’t know if you can call something a cure if it costs that much. Even if the patient isn’t directly paying for it, our society is, so it won’t be possible to treat many people at that cost.

Another issue is the cost of developing treatments, especially for rare diseases. In pediatric immunology, there are genetic diseases involving over 500 genes and 20,000 specific mutations, so we cannot spend millions of dollars designing therapies for each one. We’re trying to figure out how to drive down that cost. Specifically, I’m interested in designing platform therapies where the delivery and formula could stay the same between different conditions, with only small parts, like the CRISPR targeting sequence, changing.

How do you think about health justice and your career?

When I was younger, I was taught that if you do good work, it’ll end up in papers and if it’s really meaningful, then somehow a company will pick it up and turn it into a medicine that will help people. But as I’ve grown up, I’ve realized that’s not really how it works. There are societal and financial interests that drive why certain areas of science or diseases receive more attention, which in turn affects how much we understand or whether we develop therapies. I specifically chose UCSF for residency because it’s a public institution with a longstanding commitment to health justice. What often goes unmentioned is the researcher’s role, their chosen focus, and the envisioned outcomes of their work, in improving health equity.

What do you do for fun?

A lot of my life is centered around children: my clinical work, my research work, and I have a one-year-old baby. A lot of my time is spent with my son and experiencing the joy of seeing him learn and grow. I brought him to the Cal Academy a couple of weeks ago and he just lit up and loved it so much, especially watching the fish in the coral reef. I also like running and rock climbing, although these things get a lot less of my time now since having a one-year-old is pretty all-consuming.

I also used to work with the Buck Scholars Association, a nonprofit mentorship and scholarship program for under-resourced high school students to guide them into college. We have sent 40 or 50 students to great four-year colleges, mostly on full scholarship. Two-thirds of those students are first-generation college students.

What keeps you motivated?

My motivation is the patients, and understanding their disease and experience, trying to create better diagnostic tools and therapies.

What would you tell young people thinking about pursuing a career in STEM?

I want to tell them to dream big and chase their dreams, and that if they put themselves out there, they’ll get the opportunity to work with phenomenal people to do hard and exciting things. What I described today sounds simple, but what we’re doing is extremely difficult. I stand on the shoulders of giants and we’re trying to accomplish a vision of genome editing that people have been dreaming about for 40 or 50 years, but didn’t have the tools. And now, thanks to the phenomenal researchers at the IGI and others, we finally have the tools.

By

Marsiah LeBlanc

By

Marsiah LeBlanc