Meet an IGI Scientist: Josefina Coloma

This series introduces the public and fellow researchers to our talented scientists. We interview different IGI members to find out who they are and what makes them passionate about science.

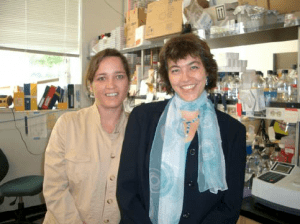

Josefina Coloma is a Faculty Researcher at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health, where she has been Co-Investigator and Principal Investigator working in close collaboration with Eva Harris. She co-founded the Sustainable Sciences Institute and serves as its Executive Director.

Where are you from?

I am from Ecuador in South America.

How did you become a scientist?

Ecuador is a very biodiverse country – we have the Amazon basin, the Galapagos islands, tropical forests. I grew up exposed to nature, and I wanted to be a marine biologist. In the education system there, you choose your focus earlier than you do here in the US. At the age of 14, I had committed to studying biological sciences. After that, I went to the Universidad Católica in Quito. I got a very high quality education there, writing a thesis on the biochemistry of snake venoms. I read a lot of papers by James W. Larrick, who had studied snake bites in the Indians of the Ecuadorian Amazon.

When I graduated, I knew I wasn’t done — I wanted to learn more but Ecuador offered no graduate school back then. I got an opportunity to go in Colombia for a few months to take a course on serological assays, and the same year to Cuba to learn monoclonal antibody technologies, which were emerging in Latin America. And I said, “Oh my God, this is what I want to do. This is science! This is discovery!” It was like an explosion and I forgot about marine biology — I wanted to be a bench scientist.

How did you go from that realization to actually becoming a PI?

The research hub in South America in the late 1980s was in Cuba. They were betting on tourism and science to save the country, making interferon and other drugs to sell to the world. I was at a conference and I saw this gringo American, a tall guy with a mustache. And someone said, “Do you know who that is? It’s James Larrick.”

You know, you idolize someone and then they’re a real person! I met him and just gushed about reading his papers. He invited me to do a summer internship at his biotech company in the Bay Area. I packed my suitcases for a summer internship in California and I never left, it’s been a 30-year summer.

A lot of people have a plan in life and you go through A, B, C, D, E to get to Z. But there’s also the winding road. You don’t know where the bends are, but you still get to Z. Doors open and if you’re prepared and enthusiastic, you keep jumping through them. I never despaired like, “Oh my God, what I’m going to do! What’s my plan?” because life isn’t very linear.

I obtained my Ph.D. at UCLA, in Microbiology and Molecular Genetics studying monoclonal antibody engineering. I loved it, but I didn’t want to be a PI or have my own lab. I did not think I was cut for it, for always fighting for grants, papers and beating your own drum. I had met Eva Harris at a conference in Cuba in graduate school. When she was offered a position at Berkeley, she said, “Come and let’s work together.” So I have been a researcher in her lab for many years.

And you’re also a PI!

I did not want to be a PI, but I ended up being one because I realized that I could have a lot more impact if I worked within the system. It also became clear to me that you can’t fight yourself, and this path was eventually open for me.

Because one of the largest projects I worked when I came to Berkeley involved evidence-based community mobilization for dengue control, including a cluster randomized control study, I became interested in field work in research that involved communities. I’ve led a number of projects focused on community engagement for mosquito and infectious disease control in Central and South America. I realized that I can change a lot of things with my knowledge and my status in the US regardless of politics. So I have done research or collaborated in many countries.

What’s it been like to collaborate with Eva Harris?

It’s been a real partnership. Our lab is like a little United Nations. We have people from all over the world, and since Eva loves dancing it’s basically a pre-requirement that you like dancing to join the lab! Joking aside, Eva supported me in growing my own space within her program for many years, and becoming my own self, my own scientist.

We’ve been like sisters. I met her 25 years ago, and ever since we’ve been working together in different capacities. Eva and I partnered first to create technology transfer courses, bringing molecular diagnoses to Ecuador, and later to many other countries. She was awarded a MacArthur genius grant for that work, and with that money funded the Sustainable Sciences Institute, where I am the Executive Director. SSI is a non-profit that works with partners around the globe to help them better meet the public health care needs of their own communities.

Do you have a funny story about research?

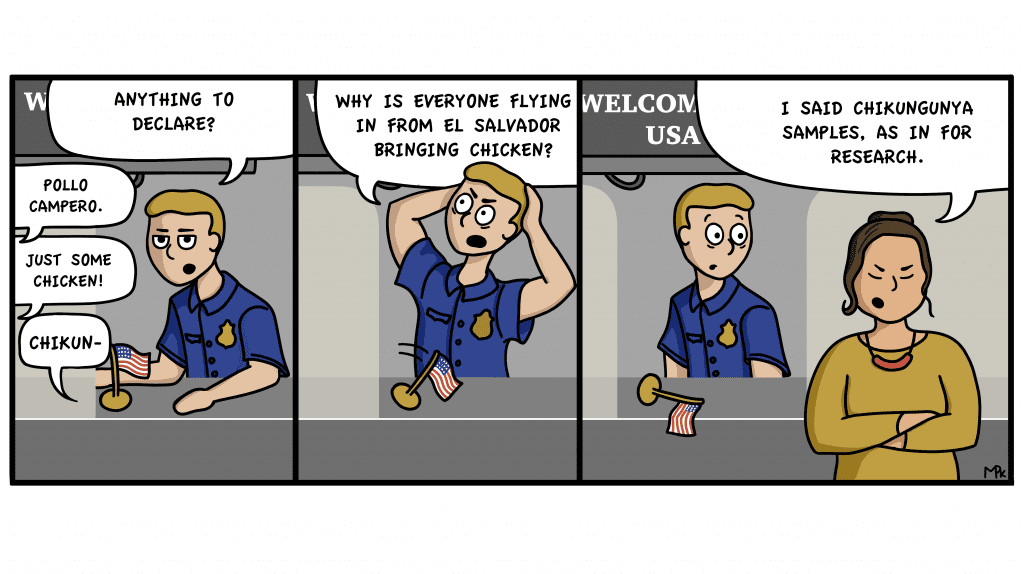

Because of our work that we do internationally, we often travel with lab materials and reagents. It’s cheaper than sending things — we’re burros for lab materials. Sometimes we travel through El Salvador. Now in El Salvador, there’s a famous roasted chicken, pollo campero. Everybody in the airport in El Salvador gets on the plane carrying a bag of chicken.

One of these times, during the chikungunya virus epidemic in Central America, I was coming back through SFO and declared at customs that I had a box with diagnostic samples from our pediatric cohort study in Nicaragua.

So I got to the customs counter, and there’s this small guy there; he looks like a mouse. I can see his face. And he just says, “What do you have there? Chicken?” And I say, “No chicken.”

But he said, “Why do you have that chicken?” in this disrespectful and demeaning manner.

I said, “No, I’m bringing biological samples. Here’s my CDC permit.” As a woman scientist and as a Latina scientist, you’re dismissed. Because you are not the white man in a suit, you must be bringing a chicken — but I was bringing chikungunya antibodies.

If you weren’t a scientist, what would you be doing?

I would probably be farming. After I finish my career here, my plan is to go back to full-time farming in Ecuador. I think we need to go back to our basic food supply chains and understand where things come from. If people were more connected to the basics of food chains, we would have a better planet. I’m very concerned about that.

Tell us about someone or something that inspires you.

In Brazil, I was first exposed to ideas from Paulo Friere’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. That informed my research approaches and I became super interested in community-based participatory research. The idea is that people are not just the subject of your research but also participate and collaborate with you on designing the study, and the first people to receive data rather than scientists holding their data until they get published.

The subjects of the research should be the first ones who benefit from the research. This became my guiding principle, and I have committed to only do research that involves community as collaborators.

Anything else you want to tell the world?

This pandemic year has shown us that you can have whatever plan you want and someone or something will throw a wrench in it. Disease happens, kids happen, divorce or marriage or death — all these life things can really alter your path. You can decide that work is your only priority, or you can decide to take the slow road right now. You get to the same place having more fun and adventures. I think there’s overvalue in the academic system around papers as currency. I publish, but that’s not all that matters to me at all. I love working onsite, training people, mentoring people… There’s not only one measure of success and there’s not only one way to be a scientist.

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson