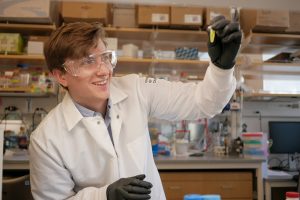

Meet an IGI Scientist: Chris Baehr

This series introduces the public and fellow researchers to our talented scientists. We interview different IGI members to find out who they are and what makes them passionate about science.

Chris Baehr is a postdoctoral research in the Wilson lab at UC Berkeley, where he works on nanomaterial tools for delivering CRISPR to neurons in the brain for future applications in conditions like Huntington’s disease.

Where are you from?

I’m from Columbus, Ohio. I grew up outside of the city in a suburb, Gahanna. I did my undergraduate at The Ohio State University, and then moved to California to do my graduate work at UC Davis.

Why did you become a scientist?

My dad is a primary care physician, my mom is a mammography technologist, and a few other family members are in the medical field. My aunt and grandmother are nurses. I really valued what my dad and other family members did, helping people directly, but it was not something that I wanted to do myself. I realized that when I did a Take Your Child to Work Day and I found that interacting with patients was not something I would enjoy. So I thought, what could I do that would be fun for me, and would have an outsized impact on the world and the people around me? The best kind of answer I could come up with was science and innovation. In science and engineering the design space and need is so large, that if you are creative, you can really have an impact for the better.

Do you have any funny memories of lab work?

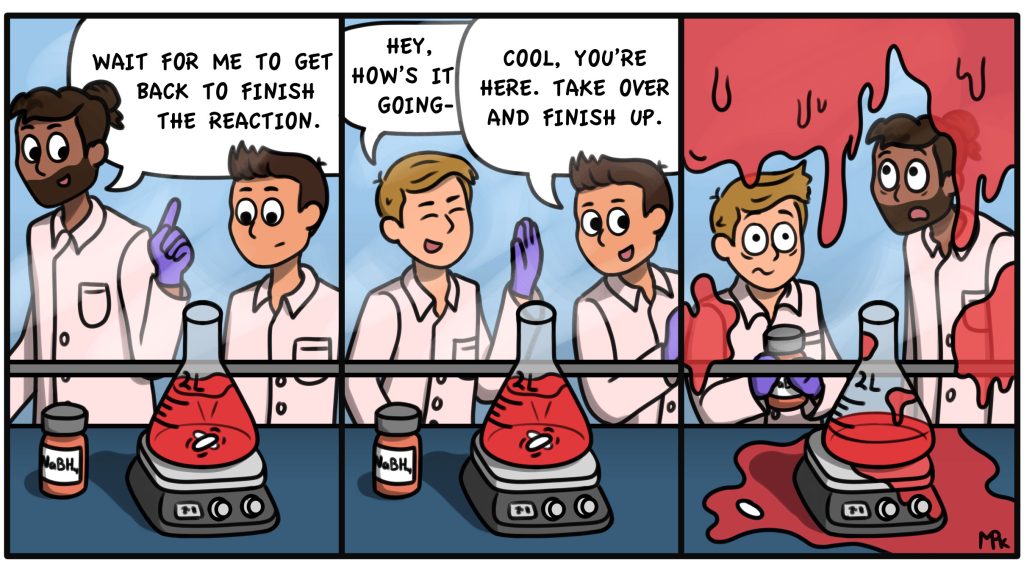

One of my first memories as a researcher was when I started working in an artificial blood research lab as an undergraduate at OSU. The focus of the work was to create artificial blood products that could be used in lieu of blood transfusions and in transplant medicine. To make this artificial blood, you have to get molecules of hemoglobin, the red protein that carries oxygen, to polymerize – meaning, to stick together. But you don’t want the polymers to get too big either, so after a certain time, you have to stop the polymerization reaction by adding a strong reducing reagent. They had gotten this process to work in the past, but were now having trouble getting the right-sized polymers. So the senior graduate students and postdocs decided they would have the new team of undergraduates help them run one more reaction.

An important thing to keep in mind here is that the reaction used bovine hemoglobin, so the liquid mixture was the color and roughly the viscosity of blood.

There was an undergraduate before me who had started a liter flask of hemoglobin stirring with the polymerization chemical. When I came in later, he informed me that it was his time to leave, and without much discussion he headed to his next class. About as soon as he left, I realized that the reaction time was up, and deciding that every second of the ~6 hour reaction was critical, I determined that the reaction would have to be stopped immediately. So I quickly calculated the mass of reducing reagent that would be needed, and added it to the solution… Unfortunately, the mass I had calculated was off by a factor of 10.

Within two minutes, a veritable geyser of blood foam started shooting out of the reaction vessel – at least six inches out of the flask.

A few minutes later the postdoc came back to the lab, coffee in hand. He had apparently only left for a short coffee break and was very unhappy! He had told the other student to wait for him to help with this step, because it can be pretty violent even when you do it right.

After that I assumed my research career was over. But as luck would have it, this batch of polymers had better properties than most of the previous batches, so they kept me around. But the reducing reagent was kept under close guard from then on.

What do you like to do besides scientific research?

I do a lot of outdoor activities. In the winter I go skiing quite a bit and in the summer I climb and do a lot of backpacking. I try to go to Yosemite as much as I can. The outdoors are a great place to recharge for me.

What do you see is the role of science in the community?

Science is a tool humans use to examine problems and, hopefully, drive progress. Scientists and engineers use research to help bring about better circumstances, faster and more efficiently than they otherwise would come about.

If you hadn’t become a scientist, what would you have wanted to do?

What drew me to research was helping people and having an impact. The only other thing I can think of that can have a similar impact is government. I think being involved in local government could be incredibly rewarding.

Do you have any role models?

My high school science teacher Mr. Mackey was a wonderful teacher. He challenged me to think independently and creatively about problems. A core tenant of his teaching style was to give students space to consider and solve problems without his help. This really helped me throughout college and likely built the foundation for my experience as a graduate student and researcher.

There’s also my former PI at UC Davis, Dr. Lam. He is an energetic and creative researcher, but he also goes out of his way to help folks when they need it. That environment taught me a lot about how to be a good leader and how to set priorities.

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson