New Research Uncovers Humans’ Closest Microbial Relatives

Newly identified archaea share a common ancestor with eukaryotes

In a new paper in Nature Communications, researchers from Jill Banfield’s lab uncover new groups of Asgard archaea, a type of microorganism that shares a common ancestor with eukaryotes — including humans. Researchers from the lab of Brett Baker, a former Banfield lab member who now runs a research group at UT Austin, contributed to the phylogenetic analysis of the genomes.

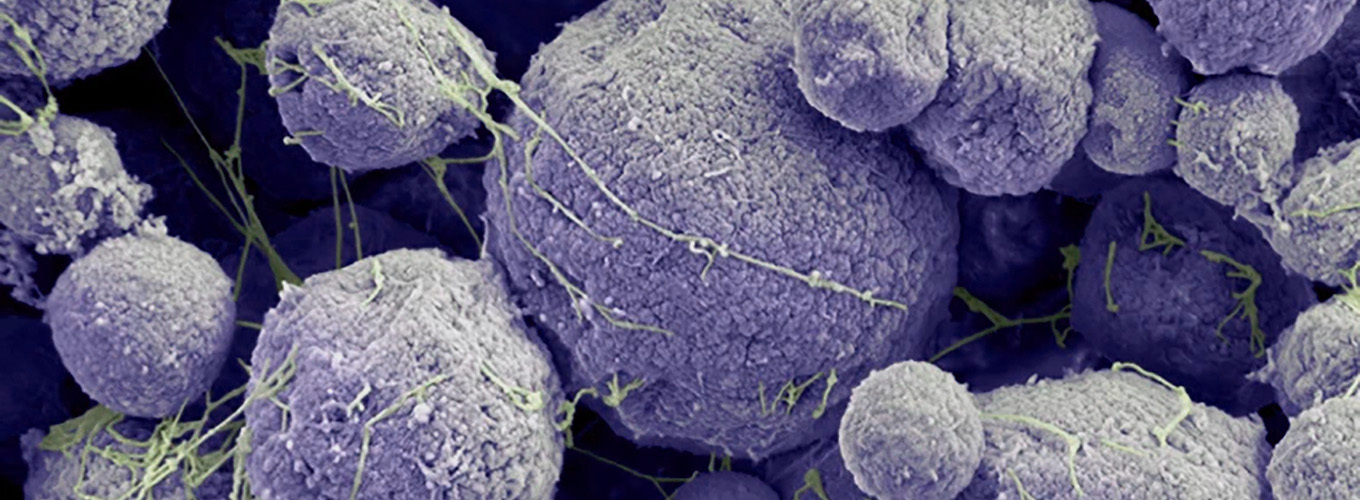

Previous studies had revealed pieces of genomes from Asgard archaea, which contained genes thought to be unique to eukaryotes. But researchers couldn’t rule out the possibility that the surprising findings were the result of contamination — until now. The Banfield lab has now manually put together three completed genomes for different Asgard archaea collected from the backyard of Banfield’s property in Lake County, California.

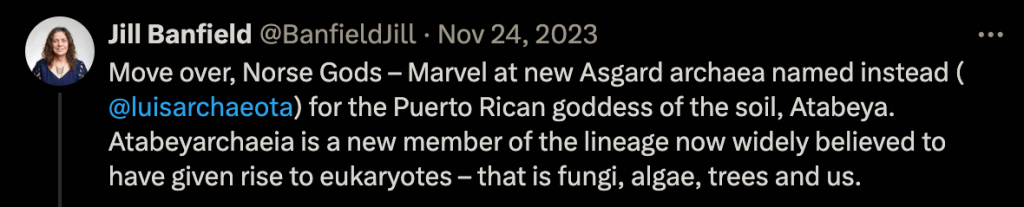

One of the perks of discovering new organisms? Naming them. Asgard archaea were first identified in in a deep-sea hydrothermal vent near a rock formation resembling the castle of the Norse god Loki. In Norse mythology, Asgard refers to the dwelling place of the gods. It has become convention to name new Asgard archaea after Norse gods.

When first author Luis Valentin-Alvarado, a researcher from Puerto Rico who recently earned his Ph.D. with the Banfield lab, completed the genome of one of the new species, he wanted to name it after a female or non-binary God, since so many species were already named for male gods. Banfield said, “What about naming it after a Puerto Rican goddess?”

They chose Atabey, a goddess in the cosmology of the Taíno people, who are indigenous to Puerto Rico and other Caribbean islands. Atabey is often referred to as Earth Mother by the Taíno, and represents fertility and abundance. She is said to be connected with the soil and fresh water.

“I go back to Puerto Rico about once a year,” says Valentin-Alvarado, “I give talks on my work and bring what I’m doing in Berkeley back to Puerto Rico. Now I’m bringing Puerto Rico, and my identity, back to Berkeley and wherever else I go and reminding people where Puerto Rico is on the global scale.”

Last fall, Valentin-Alvarado won an award at SACNAS for his talk on Atabeyarchaeia.

Asgard archaea have been found in the deep ocean, hot springs, and California soil, suggesting they are likely ubiquitous across environments. The researchers are especially interested in the connection between soil Asgard archaea like Atabeyarchaeia and microbes that make methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Initial results suggest that Asgard archaea compete with methane-making microbes for soil resources.

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson