Perspective: Could The Hornless Cattle Editing Error Be Prevented?

Editing errors can be minimized with community standards and improved regulation.

In late July, the academic pre-print paper repository bioRxiv published a paper entitled, “Template plasmid integration in germline genome-edited cattle,” by FDA scientists Alexis Norris, Stella Lee, Kevin Greenlees, Daniel Tadesse, Mayumi Miller, and Heather Lombardi. This response article is written by members of the IGI’s staff and scientific leadership and is intended to provide perspective on this news and to clarify potentially misleading interpretations by other media sources.

What do I need to know?

A company failed to notice extra bits of DNA in their genome-edited cattle; the editing community should consider it standard practice to check for this type of error, which is easy to detect.

The sections below provide more detailed information and analysis.

What’s the background?

In agricultural settings, developing horns are routinely removed from dairy calves—a very painful procedure for the animals. A team from the company Recombinetics set out to use TALEN-based genome editing, a technology that pre-dates CRISPR, to eliminate the need for dehorning. The group inserted a naturally existing bit of DNA from another breed to make dairy cattle that don’t grow horns at all. Learn more in our in-depth blog post.

What does the paper say?

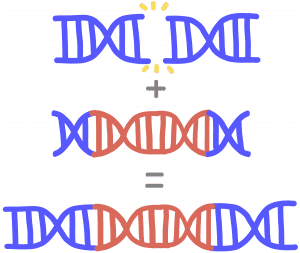

In the TALEN system, engineered proteins cut DNA at the desired site, activating repair processes that can edit DNA. Researchers provide “donor” DNA with the desired changes, and the cell uses this sequence to patch the DNA break during repair, adding in the desired sequence. In this case, the hornless donor DNA sequence was delivered as a part of a larger, circular piece of DNA.

In this paper, FDA scientists found that some of the edited calves didn’t just end up with the hornless sequence—the entire circular DNA sequence had been patched in too. The scientists who made the hornless cattle had not noticed this mistake.

Why might there be confusion?

People are naturally concerned about whether this means genome editing is unsafe. This DNA insertion probably didn’t affect the cattle and wouldn’t harm someone consuming milk from dairy cows with the same DNA changes, but we still want genome editing to be as precise as possible!

It may sound like this type of editing error is difficult to prevent or to detect. The good news is that similar mistakes are actually easy to avoid by using different types of donor DNA and simply checking genome-edited organisms more carefully.

What can we really conclude?

- Editing errors can happen and not everyone knows to look for them.

- The error made in this case could be detected easily by someone who looked for it.

- In the lab, it’s fine for occasional unwanted editing errors to occur—as long as researchers detect them and don’t use those cells or organisms for commercial development or medical purposes.

- To safeguard against errors like this, the scientific community needs to come together to discuss best practices, ensure community-wide adoption, and inform regulatory guidelines.

Bottom line:

Overlooking errors of this type is unacceptable. The editing community should form community safety standards and agencies regulating genome-edited livestock should mandate checking for this type of error along with a standard panel of other potential DNA changes.

Closing thoughts:

Genome editing holds great promise. In agriculture, we can learn from nature, and even mimic it in ways that improve animal welfare and food production. Scientists who perform genome editing and regulatory agencies who ensure food safety need to form community guidelines and improve regulations to make sure errors like this don’t go undetected.

At the IGI, we are trying to address these issues head on. We contribute to the NIST Genome Editing Consortium, which is working to generate clear genome editing standards, and we periodically provide regulators with information and comments on proposed structures for genome editing oversight. We encourage others in the editing community to take part in shaping guidelines and regulations, to ensure the safe use of genome editing technology moving forward.

Media contact:

If you are interested in speaking with one of our scientists about this paper and our perspective, please email igi-press@berkeley.edu.

You may also be interested in

Wolf Prize Laureate Brian Staskawicz on 40 Years of Plant Immunity Research

Announcing the Rising Stars Program: A New Collaboration Between the IGI and Historically Black Colleges and Universities

Breakthrough Method Enables Rapid Discovery of New Useful Proteins