First Clonal Rice Seeds Are an Agricultural Dream Come True

For 10,000 years, the major world food crop, rice, has reproduced sexually, rearranging its DNA with each generation and often losing desirable traits… until now.

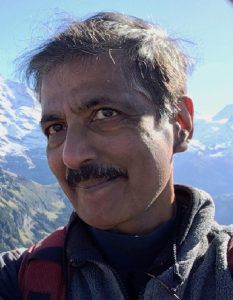

What do you think of when you hear the word “asexual reproduction”? If you are an agronomist thinking about how to feed a growing planet, this phrase is music to your ears. A team of scientists led by IGI Investigator and UC Davis Professor Venkatesan Sundaresan have figured out a way to make rice reproduce asexually and thus made an agricultural dream come true. Published today in Nature, the work describes a groundbreaking way to allow a rice plant to make seeds that grow into a clone of the parent. This is an extraordinary advance in agriculture, as it will eventually allow farmers to plant and replant seeds from elite plant varieties, all without losing any of their valuable traits, most notably yield (rice provides >50% daily calories for half the world’s population).

A worthy quest

It has long been recognized that enabling asexual reproduction in major world food crops would herald a substantial shift in global agriculture. Many crops grown by farmers worldwide are produced by genetically crossing two inbred parents to produce ‘hybrid’ seeds. The resulting seeds outperform either parent, a phenomenon of biological synergy known as ‘hybrid vigor,’ sometimes producing twice as much grain yield. Unfortunately, when the hybrid goes through sexual reproduction, its DNA is shuffled and many seeds do not inherit the elusive combination of genes that create hybrid vigor.

If robust hybrids plants could be easier to breed, propagate, and distribute, their cost would be reduced, making them accessible to farmers in developing countries who are most in need of the extra food. “This is a major breakthrough for plant breeding,” says Brian Staskawicz, IGI’s Scientific Director of Agriculture. “This would have a major impact, as small holder farmers could save their seed from generation to generation and still maintain the high yields afforded by hybrid seed without the added cost.”

A number of plants are known to reproduce asexually in the wild, a process also known as ‘apomixis.’ These include blackberries, dandelions, and some grasses (not exactly dietary staples). However, scientists have had relatively little success in genetically manipulating any sexual plants to reproduce this way, let alone major food crops. Sundaresan and his colleagues are the first to realize this lofty goal.

A pair of tweaks is all it takes

Two main roadblocks prevent asexual reproduction– a process called meiosis and the need for a sperm cell. To create clonal seeds, the team found clever ways to tackle both issues.

To stop meiosis, they used CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, which lets scientists alter specific DNA sequences, easily inactivating genes or adding in new material. Meiosis is a stage of sexual reproduction that shuffles DNA sequences around and divides chromosomes into different egg cells. The group built on a strategy developed by co-author Raphael Mercier at INRA, France, and used genome editing to disable three critical meiosis genes, without the need to add any foreign DNA. With meiosis disabled by genome editing, the rice genome stays the same. Next, they had to bypass the fertilization step to allow embryo development and avoid introducing DNA from sperm cells.

The key insight behind this advance came from the study of a rice gene called “Baby Boom 1,” abbreviated BBM1 in Sundaresan’s laboratory. Lead author Imtiyaz Khanday, a postdoctoral scientist in Sundaresan’s lab, figured out that this gene is active in a rice plant’s sperm cells, and serves as a trigger for the fertilized egg to start developing into an embryo and eventually a whole seed. The researchers reasoned that if they could turn the gene on in an egg cell, they might be able to bypass the fertilization step, triggering embryo growth without sperm, a process called parthenogenesis.

Once the scientists disabled meiosis and introduced BBM1, the egg cells grew into embryos identical to the parent rice plant, eventually forming clonal seeds. Critically, the group planted these clonal seeds to grow a full rice plant, then planted its seeds, and continued the process over three generations. Even the great-grand plants were identical to the starting plant, an important indication that the strategy should work to keep hybrids reproducing as clones over many growing seasons.

Making a deep impact

Sundaresan and his team are gearing for the path ahead, hoping to improve upon their initial work and introduce a variety of clonal hybrid crops to the world.

“We were actually surprised as well as excited that it worked as well as it did in our very first experiments,” explains Sundaresan. “Now that the road has been opened, it would be fantastic to have it working at maximum efficiency out in the field, so farmers who can’t afford hybrid seeds could still obtain the full benefits of hybrids from their home-grown seeds.”

It’s particularly exciting to note that the genes tweaked in this study are found in other plants, so the same approach should allow development of asexually-reproducing corn, wheat, tomatoes, and other important food crops.

The long-term goal is to make clonal hybrid seeds available to smallholder farmers in the developing world, who stand to benefit the most from access to high-performing crop varieties.

“All scientists dream about making a positive impact on the world, and what better place to start than to increase the food supply on the planet? We know that tiny naturally occurring genetic changes can make a major impact on a crop; the beauty of CRISPR is we can precisely ‘touch up’ a crop’s genetic makeup by making such tiny changes and thus create a trait that is planet-friendly,” says Fyodor Urnov, a visiting scholar at the IGI who is working to translate groundbreaking scientific discoveries into real-world impact. “As a nonprofit, a key area of the IGI’s focus is sustainable agriculture for the developing world, and the Institute is honored to have Dr. S as its member.”

—

This study was published in the online edition of the journal Nature as “A male-expressed rice embryogenic trigger redirected for asexual propagation through seeds.” In addition to Khanday, Sundaresan, and Mercier, co-authors of the work are Debra Skinner and Bing Yang. This research was funded by the Innovative Genomics Institute and National Science Foundation.

The Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) is a non-profit, academic partnership between UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco that supports collaborative research projects across the Bay Area. The IGI’s mission is to develop and deploy genome engineering to cure disease, ensure food security, and sustain the environment for current and future generations. As pioneers in genome editing, functional genomics, and other cutting-edge technologies, IGI scientists continuously push the boundaries of science.

Media Contacts

Megan Hochstrasser: megan.hochstrasser@berkeley.edu

Venkatesan Sundaresan: sundar@ucdavis.edu

You may also be interested in

Berkeley Undergrad Receives Grant to Engineer Disease-Resistant Soybean

Protected: Announcing the Rising Stars Program: A New Collaboration Between the IGI and Historically Black Colleges and Universities

Breakthrough Method Enables Rapid Discovery of New Useful Proteins

By

Megan Hochstrasser

By

Megan Hochstrasser