DISCOVERing Off-Target Effects for Safer Genome Editing

The CRISPR-Cas9 system is a revolutionary breakthrough in genome editing–but how do we make sure our molecular scissors are safe? Now, we can search through DNA to find every last cut.

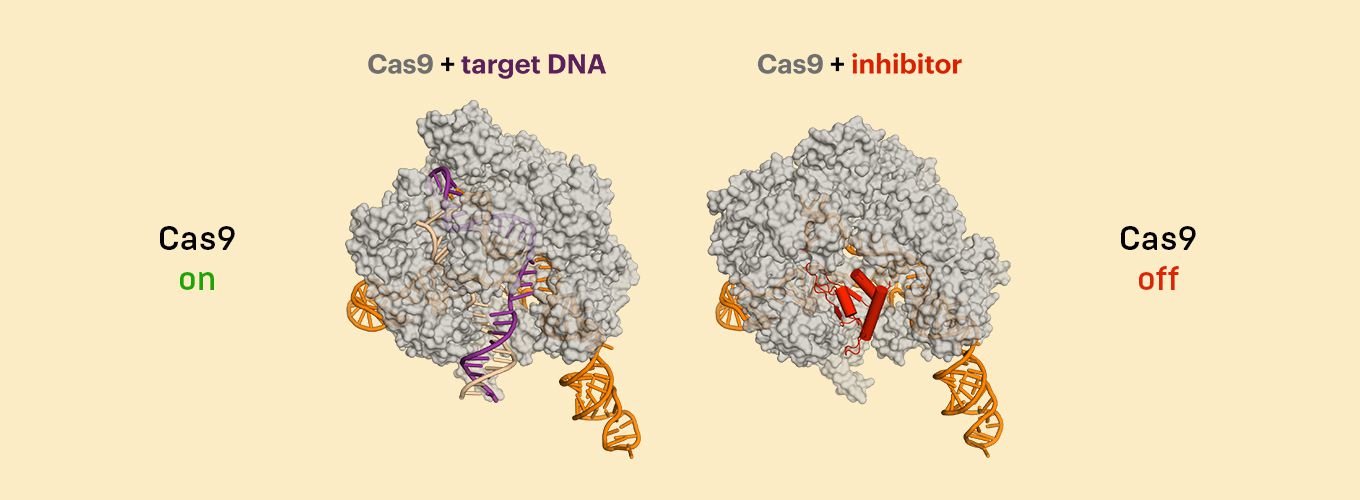

The CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing system cuts DNA at exactly the location scientists specify, but sometimes the Cas9 protein cuts the genome in other places too, creating “off-target effects.” In work published today in the journal Science, scientists at the Innovative Genomics Institute, the Gladstone Institutes, and AstraZeneca reveal a new way to identify these unwanted cuts. When DNA breaks or gets cut, DNA repair proteins flock to the site. The researchers capitalized on this phenomenon and created DISCOVER-Seq, a method that uses a DNA repair protein to identify Cas9 cut sites.

Unwanted off-target effects may be harmless, but have the potential to impair cell function, or even kill cells depending on where they occur. To use CRISPR-Cas9 proteins to treat human diseases, scientists need to know what the off-target effects are, so they can determine if the treatment is safe. This is a tough task. Former IGI Director of Biomedicine and current Professor of Genome Biology at ETH Zurich Jacob Corn explains, “Finding CRISPR-Cas off-targets can be hard. Genomes are big, and there’s a lot of real estate to search. Things get even more difficult when you’re talking about patient cells or mouse models used to test potential genome-editing therapeutics.”

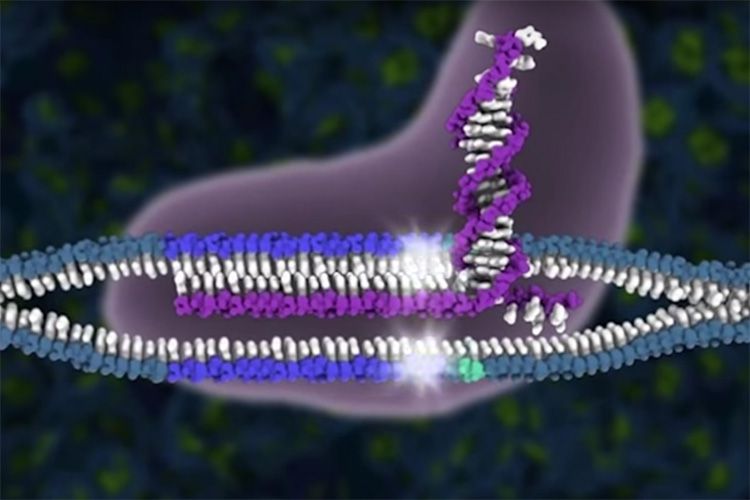

When Cas9 cuts through a strand of DNA to a form a DNA break, the cell recruits DNA repair proteins to fix the damage. Corn has previously identified some key players in the repair process. Corn and co-lead authors Beeke Wienert and Stacia Wyman wondered if it would be possible to use repair proteins to identify all the places where Cas9 and other Cas editors create DNA breaks–particularly off-target effects.

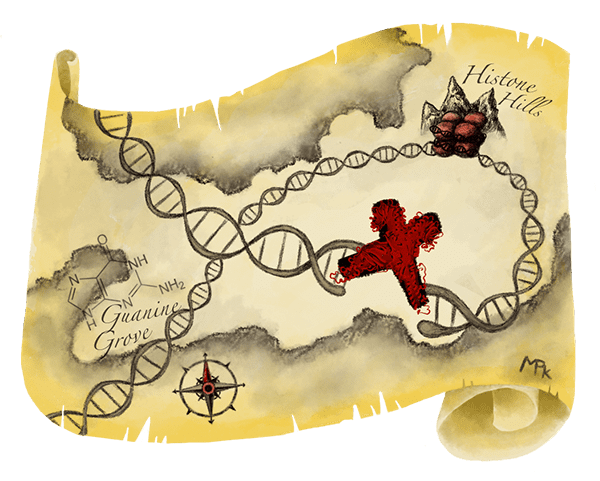

The researchers considered several known repair proteins, and found that the protein MRE11 is one of the first to arrive at DNA break sites. It marks the spot like an X on a treasure map, telling other repair proteins where to get to work. After using the CRISPR-Cas9 system, the researchers treated the cell mixture to freeze everything in place, effectively gluing the MRE11 protein to the DNA so it stays attached to the Cas9 cut sites. Next, they used antibodies to find the MRE11 protein and isolate it from the cell mixture. Finally, they sequenced the DNA glued to the MRE11 protein, to identify the CRISPR-Cas9 cut sites. They call this process DISCOVER-Seq.

Before CRISPR-Cas9 treatments can be used in the clinic, researchers must test them extensively in animals and in isolated animal and human cells to make sure they are safe and effective. While there are other systems for detecting off-targets, usually depending on computer predictions, or finding cut sites after they have been repaired. These systems usually work best in a specific cell type or animal model, and for some cell types, there are no reliable ways to find off-targets. DISCOVER-seq is the first method that can directly find the cut sites from CRISPR editing tools in any living tissue.

The MRE11 protein is one of the earliest players in a key DNA repair pathway and is present in mammalian cell lines, mice, and humans. This means it can be used to find cut sites in an unbiased way, and easily applied across different systems that were previously tough to work with. “There are some very good off-target methods out there already,” says Corn, “But they work best in highly controlled systems, like cultured cells in a lab dish. One advantage of DISCOVER-Seq is that it theoretically finds off-targets in any system where genome editing works.”

Because MRE11 allows researchers to zoom in on a cut site right after the cut is made, researchers are also finding out new things about how DNA repair works. They may ultimately use this knowledge to improve CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing.

To make this new technique available to other researchers as soon as possible, Corn and his colleagues put an early version of the paper online through the open access repository bioRxiv, and made their protocol and bioinformatic tool publicly available as well. “DISCOVER-Seq is already useful in the lab,” says Corn, “And we hope that someday it could be used to find off-targets during genome editing therapies.”

–

This study was published in the online edition of the journal Science as “Unbiased detection of CRISPR off-targets in vivo using DISCOVER-Seq.” In addition to Corn, Wienert, and Wyman, other authors are Christopher D. Richardson, Charles D. Yeh, Pinar Akcakaya, Michelle J. Porritt, Michaela Morlock, Jonathan T. Vu, Katelynn R. Kazane, Hannah L. Watry, Luke M. Judge, Bruce R. Conklin, and Marcello Maresca. This research was funded by the Li Ka Shing Foundation, the Heritage Medical Research Institute, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the Gladstone Institutes, the Fanconi Anemia Research Foundation, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the American Australian Association, and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

The Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) is a non-profit, academic partnership between UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco that supports collaborative research projects across the Bay Area. The IGI’s mission is to develop and deploy genome engineering to cure disease, ensure food security, and sustain the environment for current and future generations. As pioneers in genome editing, functional genomics, and other cutting-edge technologies, IGI scientists continuously push the boundaries of science.

Media Contacts

Megan Hochstrasser: megan.hochstrasser@berkeley.edu

Jacob Corn: jacob.corn@biol.ethz.ch

–

Selected Media Coverage:

DISCOVER-Seq: A New Tool For Detecting CRISPR Off-Targets

Synthego Blog | Meenakshi Prabhune | April 19, 2019

News of Note—Detecting CRISPR’s off-target effects; Gene variants that protect against obesity

Fierce Biotech | Arlene Weintraub | April 22, 2019

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson