“The Crop of the Future”: Why Climate Scientists Are Sweet on Sorghum

Sorghum, a heat-loving cereal grain, isn’t just getting attention from the IGI and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, but also climate scientists at the Department of Energy and Gates Foundation. So, what’s so special about sorghum?

“Number one, it’s extremely drought tolerant and can be grown well with a relatively small amount of water,” says Peggy Lemaux, Professor of Cooperative Extension in Plant & Microbial Biology at UC Berkeley and an Investigator working on IGI’s Net-Zero Farming Initiative. “Number two, it’s flood-tolerant.” Scientists expect to see both forms of extreme weather increasing around the globe.

Sorghum is grown in the temperate climates of the American Midwest, but thrives in hot climates including Northeastern and Western Africa, the American South, and parts of California. It also grows well in poorer soils than many other crops.

Sorghum is grown in the temperate climates of the American Midwest, but thrives in hot climates including Northeastern and Western Africa, the American South, and parts of California. It also grows well in poorer soils than many other crops.

“Sorghum was first domesticated in the drier areas of Ethiopia and Sudan,” says Kiflom Aregawi, a Research Associate in the Lemaux lab. “It’s an important crop in Ethiopia where it is used to make a popular Ethiopian flatbread, injera, beverages, and feed farm animals.”

Sorghum was brought to North America by ships carrying enslaved Africans. It was initially grown to feed enslaved people and farm animals in the American South. In the US today, it is used to make molasses, gluten-free breads and cereals, and animal feed. Sorghum is also used to make alcohol, biofuels, and its stems can even be used as a building material.

Climate scientists are excited about sorghum for another reason: It presents a novel opportunity for biological carbon removal, the process of using plants and microbes to help remove excess carbon from the atmosphere and store it deep in the ground. As part of IGI’s work on climate supported by CZI, Lemaux, along with IGI Investigators Jennifer Pett-Ridge, Jill Banfield, Dave Savage, and Kris Niyogi, are working together to create a superpowered version of sorghum that collaborates with soil microbes for carbon removal and long-term sequestration.

Biological carbon removal depends on capturing carbon from the atmosphere through photosynthesis. Some of this carbon is used to make more or bigger leaves, grains, fruits, and roots. Some is released back into the soil by the roots, where it comes in close contact with soil microbes.

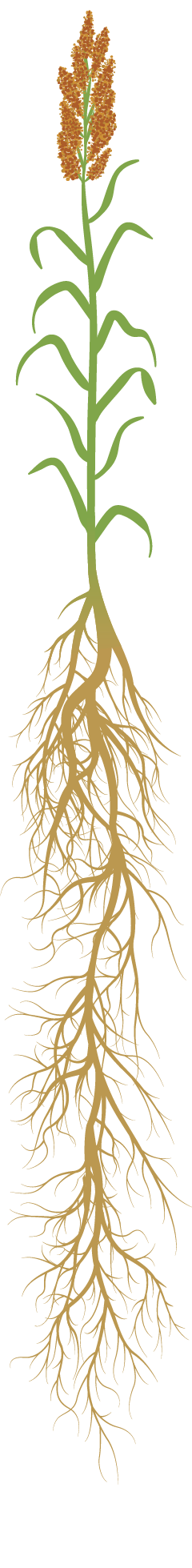

When roots are shallow, the carbon is easily rereleased back into the atmosphere. But sorghum’s deep root system can go down six feet or more.

“One of the tricky things with carbon sequestration is that often soil bacteria will take up carbon but release it back into the atmosphere. The deeper the roots, the more likely you are to be able to keep more carbon in the soil, while trying to keep it from going back into the atmosphere,” says Lemaux. “And compared to sorghum, the roots of rice are really wimpy. Corn roots are wimpy too. With its deep roots, sorghum has it going.”

“With its deep roots, sorghum has it going.”

The IGI team’s larger plan can be described in a few steps. The Savage and Nyogi labs are working on optimizing photosynthesis which will both take more carbon out of the atmosphere and create plants with more root biomass that can help store that carbon underground. The Lemaux lab is working to directly increase root mass and depth, using CRISPR to edit genes that improve photosynthesis and control root traits. Further down the line, the Banfield and Pett-Ridge labs will work on optimizing relationships between roots and soil microbes to increase carbon retention. In short, pull more carbon out of the atmosphere, and make sure it stays locked away in the soil.

“Our goal is to take more CO2 out of the atmosphere than we put back into it, on a large scale,” says Lemaux. “As a society, we didn’t start addressing climate change for a long time because people didn’t believe it was real. We are late and we need to put all the resources we can towards working on it in a smart way. If I can make some small contribution to that, that will make me happy.

“Sorghum is the crop of the future,” says Aregawi. “It’s exciting to be able to contribute as much as possible to one of the biggest challenges our planet is facing.”

[metaslider id=”31394″]

By

Hope Henderson

By

Hope Henderson