Cal Day 2018 Gets a Bit CRISPR

Every spring, UC Berkeley opens its doors to the wider community on Cal Day. Each department, from Neuroscience to Linguistics, invites the public to explore the cutting-edge research unfolding in labs and classrooms across campus. On April 21st, 2018, the IGI joined Cal Day festivities by guiding the public through a comprehensive and interactive CRISPR exhibit. Entitled “Rewriting the Language of Life: CRISPR DNA Editing at Cal,” participants were led through six stations highlighting the diversity and breadth of CRISPR research on and off campus.

Biology Primer: What are genes and DNA?

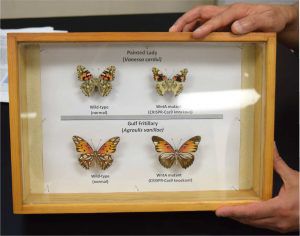

Upon entering the room, participants were greeted with brightly-colored felt and rainbow markers. This first station offered children the chance to explore how the genetic sequence of DNA affects the appearance of organisms. Each kid received a paper with a butterfly silhouette or black canvas. Blocks of color representing genes spread across DNA spanned the top of the page. Kids reached for colored pieces of felt that matched their gene color. Slowly a colorful butterfly emerged on their canvas. Kids left this station with a butterfly in hand and a new understanding of how specific pieces of DNA encode features of an organism (genotype to phenotype).

Upon entering the room, participants were greeted with brightly-colored felt and rainbow markers. This first station offered children the chance to explore how the genetic sequence of DNA affects the appearance of organisms. Each kid received a paper with a butterfly silhouette or black canvas. Blocks of color representing genes spread across DNA spanned the top of the page. Kids reached for colored pieces of felt that matched their gene color. Slowly a colorful butterfly emerged on their canvas. Kids left this station with a butterfly in hand and a new understanding of how specific pieces of DNA encode features of an organism (genotype to phenotype).

Genome Editing: How do we edit DNA with CRISPR?

After exploring the idea of genes and DNA, participants were next introduced to CRISPR-Cas9, a genome editing technology that is providing researchers the ability to edit DNA. A mounted screen showed a molecular animation of CRISPR-Cas9 locating, unwinding, and cutting DNA. Sitting on a lab bench sat a 3D-printed model of Cas9 bound to a guide RNA and double-stranded DNA. By removing some protein pieces held on by magnets, onlookers were able to peer inside the protein and learn how CRISPR-Cas9 specifically and precisely locates a designated sequence of DNA through complementary base-pairing with a guide RNA. Next to the 3D-printed model sat two petri dishes under a small black light. These small dishes held glowing red and green fluorescent E.coli that had been edited using CRISPR-Cas9. Before leaving this station, participants were invited to scroll through a forthcoming page on the IGI website: an up-to-date gallery of all the organisms edited with CRISPR. This technology has accelerated the pace of basic research by expanding the number of model organisms, offering the researchers a chance to explore previously unanswerable questions in their organism of interest.

CRISPR in Nature: Where did CRISPR come from?

Most people who walked in were eager to learn how scientists are using CRISPR-Cas9 to solve problems. What most people didn’t know is where CRISPR came from. The third station gave visitors a fun and engaging look into CRISPR’s natural role as an immune system. By playing a prototype of the IGI-created game Phage Invaders, users learned how bacteria use CRISPR proteins to fend off attacking viruses.

Editing Organisms for Research: How does DNA editing help us understand nature?

CRISPR in Agriculture: How can we use CRISPR editing in plants?

Two IGI researchers brought their projects out of the lab and into the classroom for Cal Day. IGI Entrepreneurial Fellow, Alex Shultink, displayed his glowing Nicotiana bethamiana plants under a UV black light. Alex uses CRISPR-Cas9 to identify plant genes involved in disease resistance. A deeper understanding of these genes can let us engineer crops to withstand viral, fungal, or bacterial infections. Juliana Matos showcased her genome-edited wheat, which she engineered to resist an otherwise deadly fungus. This station offered a small sample of the IGI’s extensive agricultural research projects.

Ethics Corner: How should we use genome editing?

After navigating the first five sections of the room, participants received a glimpse of what scientists can do with CRISPR. The sixth and final station invited them to think about what society should do with genome editing technology. Three poster boards each displayed a particular application of genome editing accompanied with examples:

- Treat human diseases (cystic fibrosis, genetic blindness, sickle cell disease)

- Enhance humans (stronger muscles, choose eye color, 150-year lifespan)

- Engineer plants (survive drought, prevent crop disease, more nutritious)

Society expresses a diverse range of emotions, thoughts, feelings towards these various applications of genome editing. What better way for young visitors to express these emotions than through emojis? Participants taped emojis to the board to capture their different sentiments, sometimes writing additional comments. IGI researchers and staff were on hand to begin conversations and unpack why people felt scared, excited, ambivalent, and confused.

Thank you to all our visitors and volunteers!

–

If you’re an IGI member interested in volunteering for future outreach events or if you’re not in the IGI but want to discuss developing or supporting educational projects, please contact igi-education@berkeley.edu.

You may also be interested in

IGI Seminar Series: Progress and Challenges in Delivering Cassava with RNAi-mediated Resistance to Cassava Brown Streak Disease to Smallholder Farmers in Africa – It’s Not Just About the Technology

IGI Seminar Series: Empowering Teachers, Transforming Classrooms: Advancing K-12 STEM Education

IGI Seminar Series: Writing DNA with RNA: Genome Engineering by Target-Primed Reverse Transcription

By

Kevin Doxzen

By

Kevin Doxzen