Visualizing CRISPR Through Art

Take a seat. Make yourself comfortable. What do you see?

Is this the depths of some primeval ocean? Or, are we looking up at the stars, back in time?

The image is actually genetically modified wheat embryos in a petri dish. We are not looking at the primordial past, but into an uncertain future.

To expand the narratives about genome editing, the IGI partnered with Stochastic Labs in spring 2019 and invited applications to the CRISPR (un)commons Artist Residency Program, where they would use art to explore this powerful genome-editing technology. After an overwhelming response, five talented artists were selected to participate. The result? CRISPR not as a scientific concept, but something anyone can touch, feel, see, hear, and engage with.

Of Forms Transformed to Bodies New and Strange

Kate Nichols, the artist behind the painting above, Of Forms Transformed to Bodies New and Strange, sees a divination pool. Ancient civilizations sought answers by scrying in pools of water, and we, too, want to divine the unknown. When you peer into this circular painting, you see your reflection looking back.

“We were told we’re looking at the future, but really we’re looking at our own innermost desires,” Nichols explains.

Did you glimpse a time where fields of crops no longer succumb to disease? Or, maybe you think the future is one where CRISPR doesn’t work. Nichols wants to know what you hope to gain, and what you are afraid to lose. When you look into the painting, you are really looking at yourself.

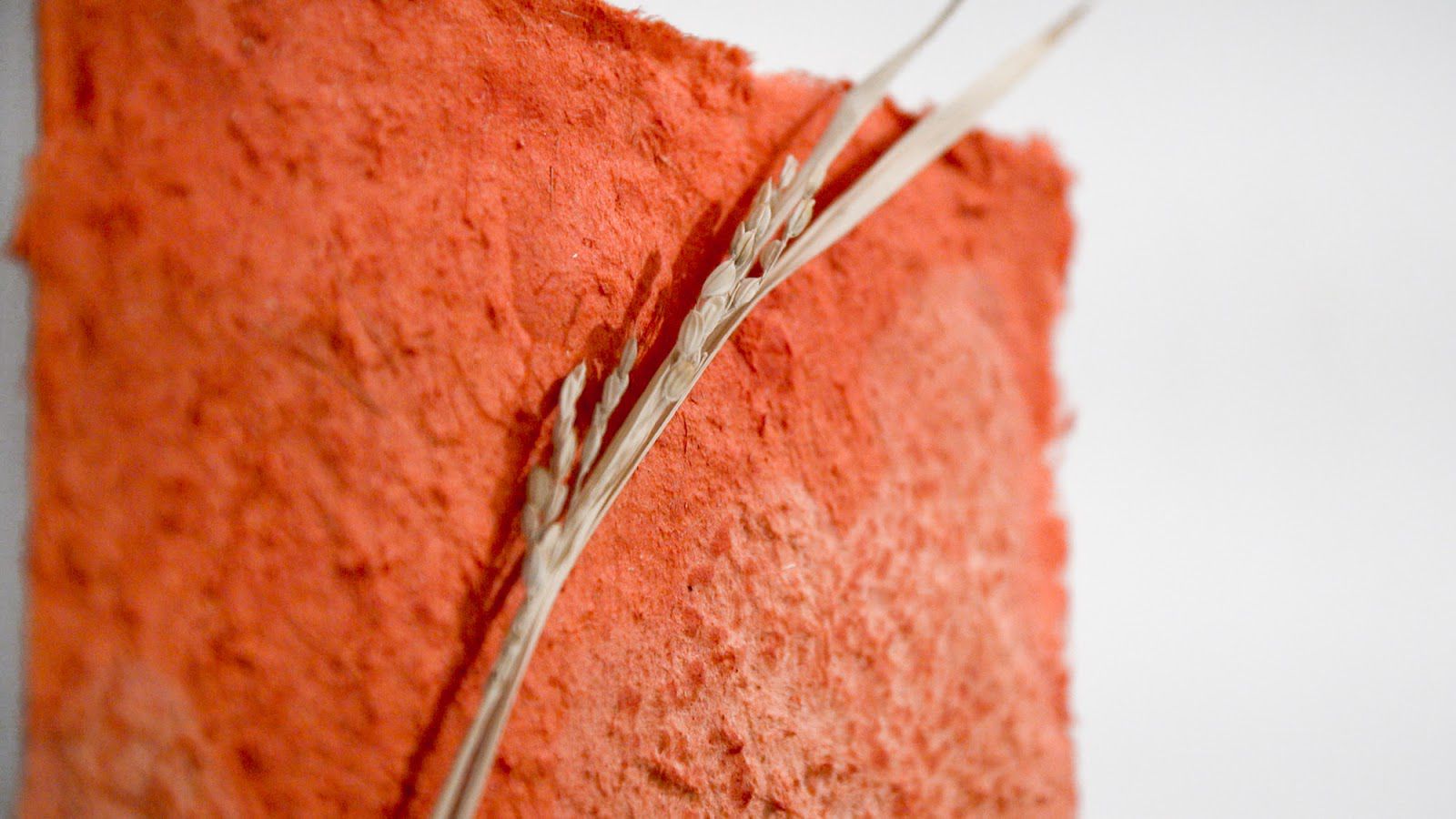

CRISPaper

To Sheng-Ying Pao, the power of reframing CRISPR lies in what is absolutely ordinary: paper. In CRISPaper, Pao revisited a cultural past in the ancient art of papermaking. Over thousands of years, farmers painstakingly converted the wild rice plant into a staple crop. Today, researchers are using CRISPR to change genes to optimize grain yield. However, rice is more than food — in ancient China, it was used to make paper. Pao took rice stalks from plants edited with CRISPR and ground the fibers into pulp. She then poured the pulp over a mesh screen. Every time she dipped the screen into water, the plant fibers would lift and resettle on top of the mesh, eventually making paper. Through the genome-edited rice plant, an ancient practice was juxtaposed with cutting-edge technology. Pao’s meditative ritual of papermaking is a counterbalance to the strangeness of the source material.

She explains, “We all know that paper wouldn’t last forever. And just because of that, we put in extra care.” This paper is delicate indeed. Light shines through in patches where the fiber is less dense. Woven into the paper, as if growing out of it, is a dried rice stalk. CRISPR might be a powerful technology, but Pao has used it to turn what is familiar into something fragile and unique.

Genomic Tapestries

Next to the earliest form of paper is what many regard as the first computer. The Jacquard loom uses punch cards to weave complex patterns into fabric and is “an early example of a society losing control over the trajectory of its technologies,” according to Alison Irvine and Andy Cavatorta. Who could have guessed that it would spark a chain of innovation that produced modern computers two centuries later?

A science educator and an innovative engineer, respectively, Irvine and Cavatorta worked together to translate the genetic code into a visual one: a 5×5 pattern of hole punches that could theoretically be read by a Jacquard loom. Depicting human chromosome 1 this way resulted in a ream of paper over a quarter-mile long.

Irvine and Cavatorta also visualized the first gene targets for CRISPR editing, creating images that were later woven into tapestries by modern Jacquard looms. Depicted are the mutation that causes sickle cell disease, a gene variant that increases the risk for Alzheimer’s Disease, and the CCR5 gene that was purportedly edited in the first babies to be born with CRISPR-altered genomes. These tapestries turn invisible genetic mutations into something that can be seen, felt, and perhaps rewoven.

Press 1 to be Connected

Of course, these small genetic variants — and potential targets for CRISPR — are not the only differences between people. With over a decade of clinical research experience, multimedia artist Dorothy Santos has talked to a lot of vendors and collaborators solely over the phone. So, when she met some of them in person for the first time, Santos was told, “I thought you had salt-and-pepper hair,” or, “I imagined you taller.”

As a queer woman of color, she is not the “default” of straight, white, and male. Neither are the gender-nonconforming characters of her choose-your-own-adventure science fiction story. In Santos’s experience, science is not neutral, but carries the biases of its practitioners. In a futuristic setting where CRISPR can be used to edit social attitudes, Santos invites you to put yourself in the shoes of a clinical trial subject and explore informed consent. If we held the power to alter future generations, what assumptions and biases would shape our choices?

And, there’s a twist: this is the kind of story you listen to — not as an audiobook, but through an automated phone tree system. The intimacy of voice mingles with the mystery of listening to someone you’ll never meet.

Even while we recall a primordial, cultural, and industrial past, these artworks grab our senses and pull us into the present. Before us is both the familiar and the strange. While we stand at this intersection, our imaginations explore the future of CRISPR — like nascent wheat embryos, blind in the darkness, but knowing somewhere there is sun.>

You may also be interested in

CRISPR (un)commons Artist Residency Program Launches

(Genetically) Engineering Learning Outside the Classroom

Teaching CRISPR Through Gaming