Joe DeRisi is a Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics at the University of California, San Francisco, and Co-President of Chan Zuckerburg Biohub. He is a PI on an IGI-funded research project to look for genes that are crucial to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In January, he talked with IGI science writer Hope Henderson about this project and how it’s progressing.

Tell me about the COVID-19 research you’re working on with IGI.

People have used many different methods to identify proteins that could be important for SARS-CoV-2 to gain entrance into cells and replicate there, causing COVID-19. Our goal is to identify which of the many host factors that have been identified are actually important — most of them are there incidentally, only a few are key players. So you can think of this as a winnowing procedure where the seed is separated from the chaff. Ultimately, we are trying to clarify the host factors that could be targeted for therapeutic intervention.

I’m in the lab every single day. This pandemic is our Super Bowl.

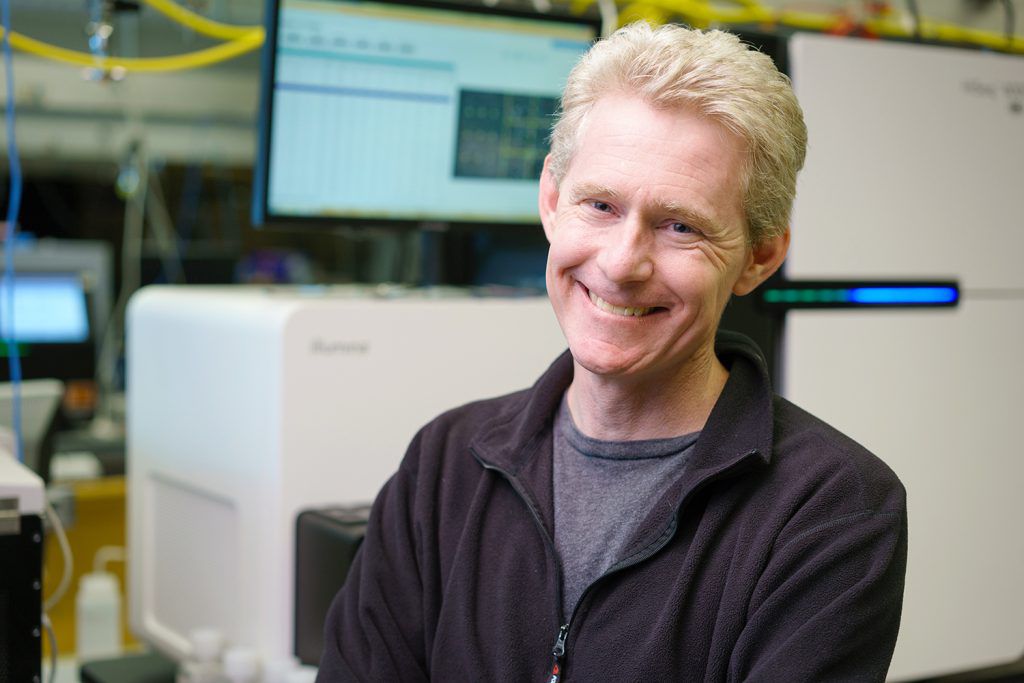

This project is a collaboration between Sara Sunshine from my lab, and Marco Hein from Jonathan Weissman’s lab, using a technique that Jonathan developed some time ago called Perturb-seq. We are reducing or eliminating expression of genes using CRISPR, and then using Perturb-seq to analyze the transcriptomes of many cells in parallel, instead of doing one at a time.

How did you come to work with Jonathan Weissman?

We’ve shared adjoining lab space at UCSF for almost 20 years, so I’ve worked in collaboration with Jonathan on many projects over that time. Jonathan’s an incredibly intelligent and sharp individual. He’s always fun and full of great ideas. I was sorry to see him leave for the East Coast.

How do you make sure your work is relevant to different strains of the virus?

We isolated the virus from patient samples in collaboration with the UCSF Clinical Laboratories and our testing hub and created validated sequence strains that are representative of the modern mutations that we are seeing in the virus.

The data set that we’re working on includes the clinical mutations as of a few months ago. There are always new mutations arising. We have plans to repeat this experiment as important new variants arise.

Where are you in the project?

The major part of the first screen has already been completed. Sara Sunshine and Marco Hein are busy analyzing the data. As is typical with these large scale experiments, the experiment actually was fairly rapid to carry out, but the analysis is where the heavy burden must be lifted.

In addition, we’ve been looking into a variety of repurposing screens that test drugs that are already approved for other purposes in the US or European Union. These are a good place to start because their safety profiles and side effects are well understood, and they’re already approved and available. We’re especially interested in combinations of drugs that might work together synergistically to defeat the virus — many screens to date have found only a small number of hits using single compounds. We’re also interested in how different strains of the virus are affected by different drugs.

Are you concerned about the new strains identified here in California?

Mutations appear in the virus all the time. There are new mutations every two to three transmission events. Some of them are in parts of the genome that code for proteins and some are in other parts of the genome. A few of these appear to become more frequently observed. The UK variant B.1.1.7 has strong epidemiological information showing enhanced transmissibility, but we have not observed it yet in our local sampling. There is a strain that was first reported in Los Angeles that has a mutation in the spike protein at residue 452 and two other residues which has also gained in some frequency. However, unlike the UK variant, we lack the sufficient epidemiological data at this time to assess whether there is enhanced transmissibility or not.

I realize that it makes a great headline to say that there “may be a scary new variant” — but it’s not a responsible headline.

There needs to be additional work to understand whether the increase in the frequency of that variant is really something to do with transmission, or whether it is an artifact of increased overall infection rate, which the whole Bay Area has seen December to January. To make solid conclusions, we would need epidemiological data or biophysical data that says that there’s really something to any particular variant. Without that, I don’t think we should be calling something scary. I realize that it makes a great headline to say that there “may be a scary new variant” — but it’s not a responsible headline. Clickbait basically, without the supporting data to understand the significance of the finding.

Do you have any quarantine hobbies?

I’m in the lab every single day. This pandemic is our Super Bowl. This is it. This is the thing I’ve been preparing for my entire career. This is not the time to stay at home and twiddle one’s thumbs.