Earlier this year, IGI Investigator Dave Savage and IGI graduate students Nicholas Karavolias and Evan Groover went to Nairobi, Kenya to teach an innovative new course aimed at empowering scientists from across Africa to use CRISPR.

What brought you to Nairobi to teach this course?

Savage: For the last ten years, the African Plant Breeding Academy has been educating scientists in modern plant breeding methodologies. Howard Shapiro at UC Davis thought that with CRISPR being a new, disruptive technology, a CRISPR course would really complement the APBA. He reached out to the IGI as a partner with the right expertise.

Given my combined interest in CO2 assimilation and genome editing, I was extremely interested in seeing this come to fruition. I’d also like to highlight Jess Lyons, who was crucial to getting this off the ground in its initial phase. Finally, I’d like to highlight the efforts of Evan and Nicholas who helped develop the curriculum and have been amazing in interacting with students.

Karavolias: Rita Mumm and Alan Van Deynze really made this course possible, from curriculum development through logistics. Rita Mumm and Allen both have extensive experience with plant breeding.

How does the course work?

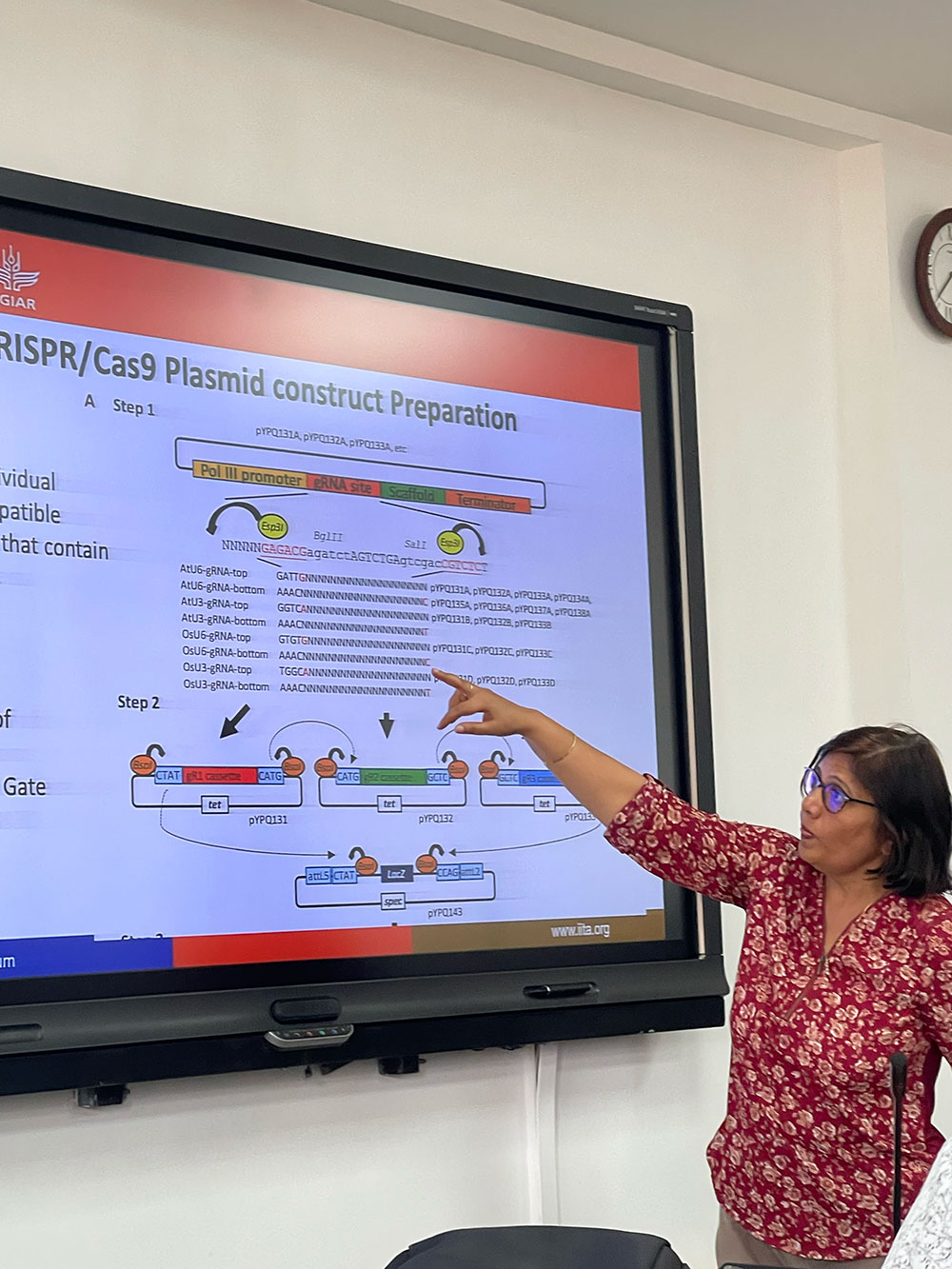

Savage: It’s an intensive, six week lab research course split into roughly three two-week blocks with a molecular biology module, a plant regeneration module, and then a genome editing and phenotyping module.

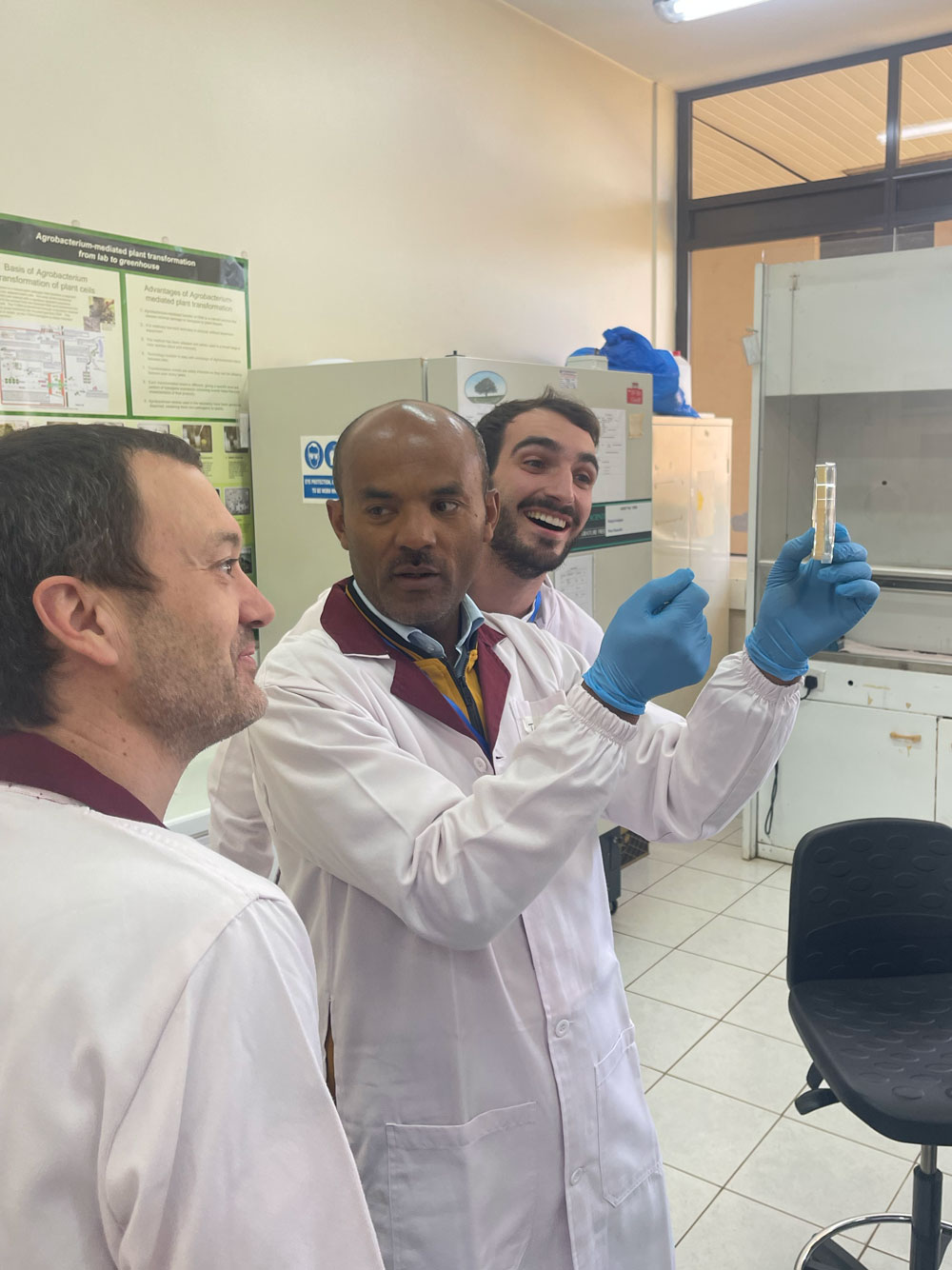

We taught part of the molecular biology component earlier this year, since that’s really where we have the most expertise. So, that’s going over things like, what is CRISPR? How do you use it? And so on. Lena Tripathi is an expert in genome-editing the banana, so her group ran the actual hands-on laboratory component. The course is taught using banana as a model, but with the idea that people will use the technology for a variety of crops. During the course, each participant will also have their own project, editing a gene of interest in a crop they choose.

Who were the participants?

Karavolias: There were a total of 11 participants from seven nations. The course is directed towards mid-career scientists with the idea that these individuals are still early enough in their careers that they could help build out the capacity to do gene editing in their home institutes and home countries.

What was really exciting is that all of our participants come from national research organizations, the equivalent of the USDA in their home nations. And because of that, they’re very connected with the needs and priorities of the consumers and other stakeholders within their nation. They bring a lot of local expertise to the course, which we get to learn so much from.

Groover: The participants were also identified as being from nations that have the potential to commercialize a gene editing crop. So, that means that there’s both the infrastructure that is required to bring a crop to scale within their institutions and a regulatory framework that allows for gene editing.

The African Plant Breeding Academy helps educate plant breeders from all across Africa. All of the course participants are molecular biologists like us, but they also have close connections with people that had graduated from the APBA. So they know breeders that have the ability to scale innovations. I think everybody there was pretty well equipped to take this knowledge and run with it.

What are you hoping the outcome or impact is?

Savage: What we view as success is them creating gene-edited plants at their home institution and bringing those into a plant breeding pipeline. After the course, they will be given a seed grant to help them with putting in place the necessary equipment to bring CRISPR technology to their institute. The funding model is aimed towards true capacity building, starting from infrastructure, with the ultimate goal of putting products in the hands of plant breeders.

Groover: For APBA, their top aims are curing malnutrition and protecting biodiversity. Another aspect of this that is really exciting to me personally is conferring agricultural self-sufficiency. That is, developing capacity for biotechnology within the continent of Africa without having to rely on external support.

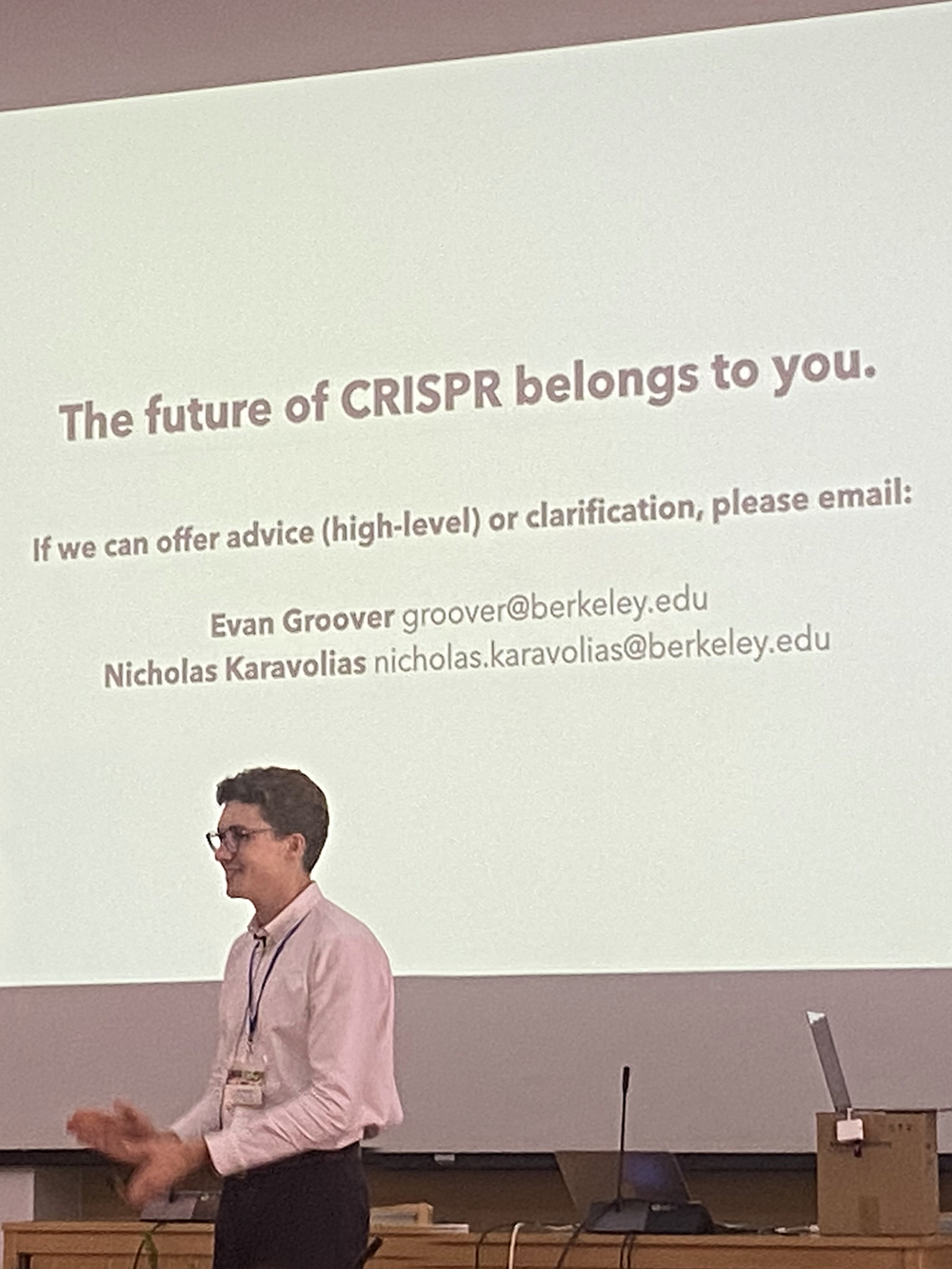

Karavolias: I think the most important thing to me in the through line with this work, or our work in the Philippines or Tuskegee is this concept of empowerment. There shouldn’t be an external player that gets to dictate how and what technology gets to develop. It’s really exciting to me to envision a future where the tools of biotechnology, be they CRISPR or something else, are in the hands of all who are interested in using them, to use them in their local contexts.

Do you think the course will impact your own work moving forward?

Groover: I’m so inspired by this experience. As a student, you think about technology and its broader importance can be very abstract. But actually getting to disseminate these tools and have experiences with other scientists who will directly benefit from their implementation for a diverse set of agricultural problems, is incredibly inspiring.

Karavolias: One very inspiring story from one of our course participants who is a plant breeder, working on growing an edited variety of maize, resistant to viruses that cause maize lethal necrosis. He understood the technology from having received the edited crop. And it was really so inspiring to see the shift in thinking of this not just as a technology that he can receive, but one he can generate for himself, for targets and backgrounds and varieties that he’s interested in working with.

In terms of impact on my career, as long as I’m engaged in this cutting-edge work, I want to be part of disseminating it, too.

Learn more about the course here.