news

Meet an IGI Scientist: Benny Ordoñez

This series introduces the public and fellow researchers to our talented scientists. We interview different IGI members to find out who they are and what makes them passionate about science.

—

Benny Ordoñez is a graduate student in the Comai lab at UC Davis. Her work harnesses the genome editing power of CRISPR-Cas9 technology for crop development in an effort to improve agriculture.

Where are you from?

I was born in Lima, Peru. My parents are migrants from the Andes mountains and the Northern Peruvian coast. I am a first-generation student, so I was the first in my family to get a Bachelor’s. I also earned a Master’s degree and now I am the first to be studying to earn a Ph.D. at a United States university.

I was born in Lima, Peru. My parents are migrants from the Andes mountains and the Northern Peruvian coast. I am a first-generation student, so I was the first in my family to get a Bachelor’s. I also earned a Master’s degree and now I am the first to be studying to earn a Ph.D. at a United States university.

Why did you become a scientist?

I always felt a strong relationship with nature. My maternal grandparents were subsistence farmers who lived in the rural highlands of Peru. They cultivated potatoes, beans, and Andean root tubers. Every season their small land was affected by biotic and abiotic stressors, so since childhood I’ve been aware of the problems that indigenous Andean farmer communities face. I decided to study biology because I wanted to contribute to research on crop-pathogen interactions and help benefit low-income farmers like my grandparents.

Once I finished my undergrad studies, I started working at the International Potato Center (CIP) studying potato pre-breeding. I used desirable genes from wild potato relatives to help breed better potatoes. After some years working there, I met my current PI, Luca Comai. He encouraged me to apply to a Ph.D. program at UC Davis and become part of his lab’s potato team.

Once I finished my undergrad studies, I started working at the International Potato Center (CIP) studying potato pre-breeding. I used desirable genes from wild potato relatives to help breed better potatoes. After some years working there, I met my current PI, Luca Comai. He encouraged me to apply to a Ph.D. program at UC Davis and become part of his lab’s potato team.

What do you like to do besides research?

I love reading history books, in particular those written by chroniclers of the Inca empire. I imagine discovering a secret message left in their stories. I also enjoy traveling and nature hiking to look at flowers and bunnies. I make jewelry too.

Describe a funny memory you have of working in the lab or in research.

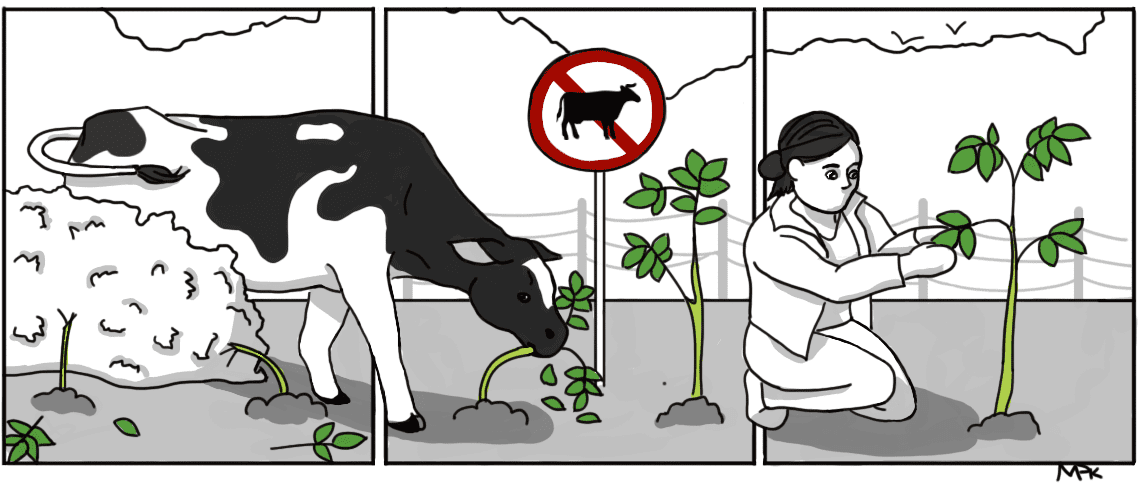

My first time planting an experiment in the field was an interesting experience. The goal was to evaluate the disease resistance of new pre-bred potato stocks under local field conditions. The field was located next to a small town in the Peruvian rainforest where there are virulent strains of the potato late blight pathogen, which caused the Irish potato famine. We scheduled observations to track the progress of the disease by determining the percent of diseased foliage.

One time during these observations, I found a couple of cows eating the potato foliage (AKA our data!). They were very docile and cute but had somehow broken the fence and gotten into the field. Their owner felt so bad that he prepared us a meal to make up for it.

If you discovered a new (protein/species/technology), what would you name it?

I would like to release a potato variety named Benita. It would be an homage to my mom, who supported me in numerous ways during my scientific career.

What would you do if you weren’t a scientist?

I think that I would still be a scientist, but I’d study archeology or the history of ancient cultures.

Tell us about someone or something that inspires you.

I think that Barbara McClintock is one of the best role models for perseverance. Her research on the genetics of corn was praised but she struggled to get a good job and advance academically, just because she was a woman. She was eventually awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. I long for a time when more women studying STEM, especially those from developing countries, receive total support from the academic field and from society in general.

Anything else you want to tell the world?

The biological world is full of hidden mysteries waiting to be discovered and anybody can be the one to uncover them. Even if you’re a woman from a developing country.