If you’re just getting into CRISPR/Cas9 editing, you might be a bit overwhelmed by all of the options available to you. Especially if you’re working in human cells. I mean, just take a look at at the Addgene mammalian CRISPR page! Which one to choose!? There are various tags, numbers of NLSes, tag/NLS locations, promoters, sgRNA+Cas9 in one vector, and the list goes on.

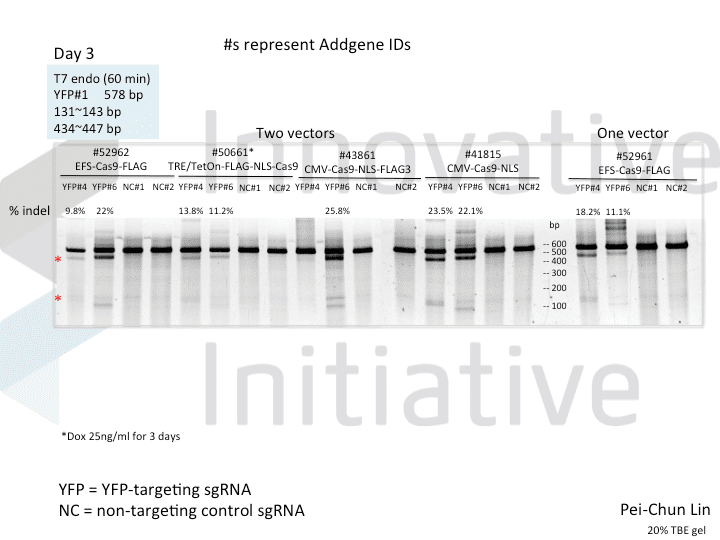

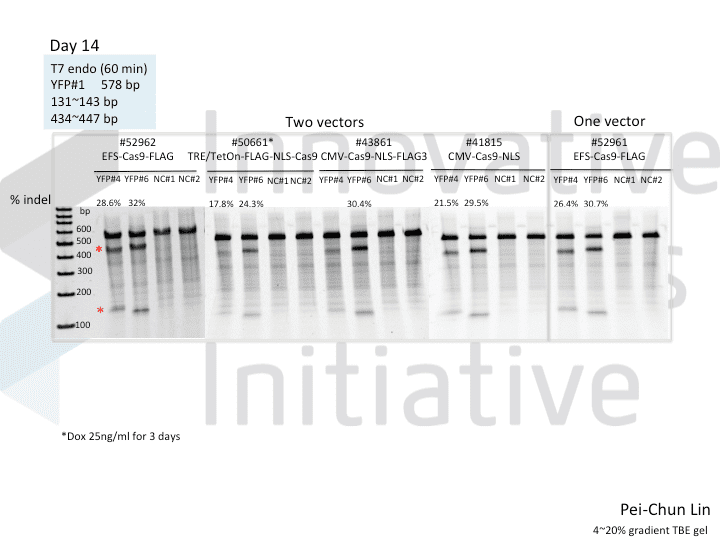

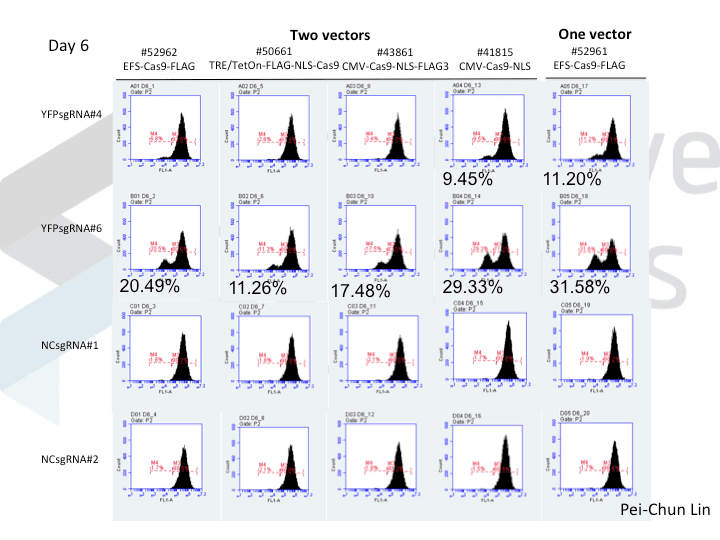

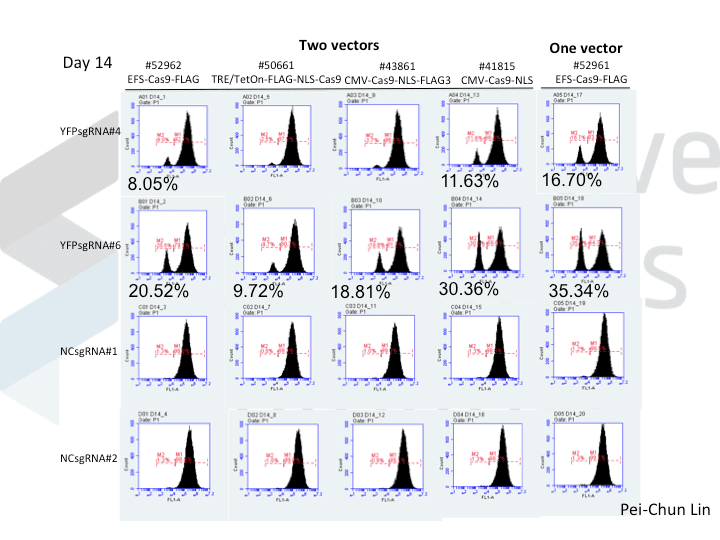

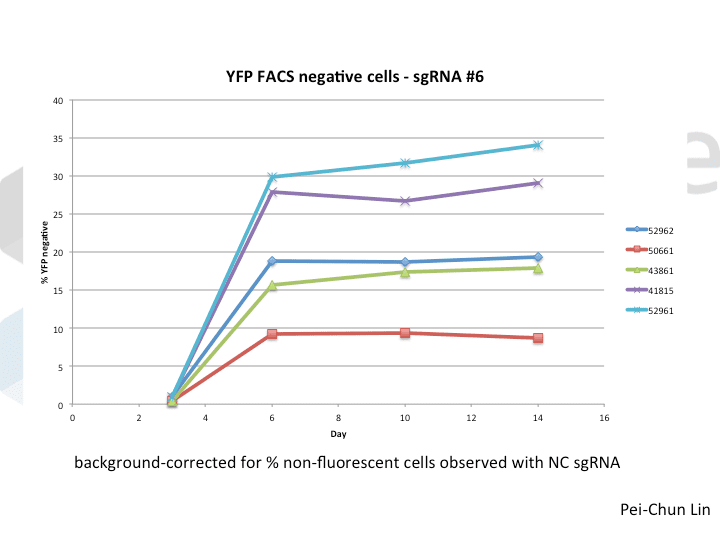

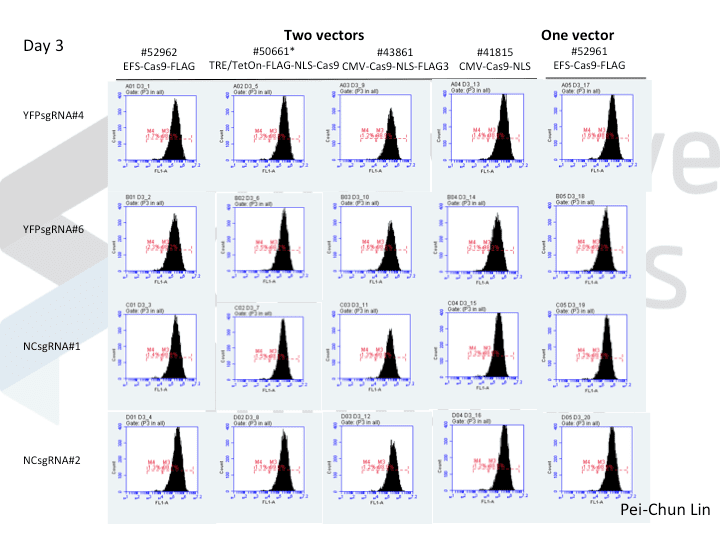

A postdoc in the lab, Pei-Chun Lin, wanted to prepare for her own knockout projects by testing a few of the Cas9 systems in an apples-to-apples comparison. This is the most vanilla use of Cas9: make a single cut and watch a gene product go away. Pei-Chun obtained a HEK293 cell line stably expressing YFP and tested several sgRNAs to find a few that worked with varying efficiencies, then used those two guides with five different setups, including both all-in-one and separate sgRNA and Cas9 vectors. She transiently transfected each Cas9/sgRNA for 72 hours, then read out cutting efficiency at various times with both YFP fluorescence (to monitor disappearance of the protein) and the T7 endonuclease assay (to monitor genomic indels caused by Cas9 cutting).

As you might expect, all systems work when given a great sgRNA (phew!), with varying efficiency (compare guide YFP#6 between Cas9s). The Cas9 system with the lowest apparent activity (Addgene #50661) has the big benefit of inducibility, so there’s still a great reason to use it. But the different efficiencies mean that sgRNAs that look decent with one Cas9 vector can appear inactive when paired with another (e.g. compare guide YFP#4 when used with Cas9 #41815 vs #43861).

Pei-Chun’s data also highlight the temporal difference between mutation and protein abundance (as might be caused by highly stable proteins). Genomic edits were easily detectable after 3 days by T7E1, but it took 6 days to even begin detect a change in protein abundance. Not unexpected, given the known stability of XFPs, but keep this in mind next time you plan a Western or other protein-based assay to read out Cas9 activity!